The Old Farmer’s Almanac — popular, with a pleasant degree of humor. It was founded during the presidency of George Washington and is still published annually today.

Author Robert B. Thomas grew up on a farm in Shrewsberry, Massachusetts, and was a self-made astronomer who enjoyed book-binding on the side. He believed that the future of the weather could be predicted based on magnetic storms on the surface of the sun.

In Thomas’ time, there were many almanacs published each year by authors who hoped to accurately predict the weather. In his memoir, Thomas writes that it wasn’t easy for him to find help with the almanac. To his competitors’ dismay, Thomas’ first farmer’s almanac was shockingly accurate. The second edition of the almanac tripled in sales compared to the first one. He continued to study the sun and the climate to predict the weather until he died at 80 years old. Thomas came to write the most successful almanac in his time.

So what is the secret that makes the Old Farmer’s Almanac — North America’s most popular reference guide on agriculture and weather and one that is different from the similarly titled Farmer’s Almanac — so enduring?

Unfortunately, most people don’t have the credentials to get a sneak peak at the secret formulas the Old Farmer’s Almanac uses to calculate the weather!

Thomas’ original formulas are kept tucked away in a black tin box in Dublin, New Hampshire, at the almanac’s offices. Twelve editors later, Thomas’ secret legacy stands. Although the editorial team admits that they use satellites and more refined meteorological technology now, they stick to some of the methods that Thomas originally used.

One of the most dedicated editors, the one who was just as witty as Thomas, and who was trained for years to take over the almanac, was Judson Hale.

Hale’s uncle, Robb Sagendorph, the founder of Yankee Magazine, became the 11th editor of the almanac in 1941.

Sagendorph loved the almanac, and he spent his whole life preparing his nephew, Hale, to be the next editor of the almanac. Hale became the 12th editor of the almanac, and began including Alaska and Hawaii in the weather forecasts, and he added pages and content to rope in more readers. He worked with more writers, and began predicting more than the weather. He started a “trends” section, where future consumer trends are predicted.

He recently passed the title of editor to Janice Stillman, who became the first woman editor of the periodical. Stillman is an avid gardener and has a degree in English, along with a master’s degree in communication.

The Farmer’s Almanac, on the other hand, was founded by David Young and first published in 1818, it is a little different.

The Farmer’s Almanac has its own weatherman, the mysterious Caleb Weatherbee, who has been listed as the meteorologist for the Farmer’s Almanac for over 100 years.

No, Weatherbee is not an ancient man with a too good to be true last name — that, of course, is a pseudonym. Weatherbee is the pen name for the top secret meteorologist, and the only person who knows Young’s secret weather-predicting formulas. Farmer’s Almanac reports that there have been seven Weatherbees throughout its history, and they do this to protect the integrity of the almanac, and Weatherbee’s work.

Both almanacs have their own approach to predicting the weather. They each use solar science, meteorology, and climatology to predict the skies’ future. For example, they believe that the activity of the sun, moon, and stars today predict the weather tomorrow. Although the almanacs cannot predict the daily weather as accurately as modern radars, they draw a lot of interest into how they glimpse into our future.

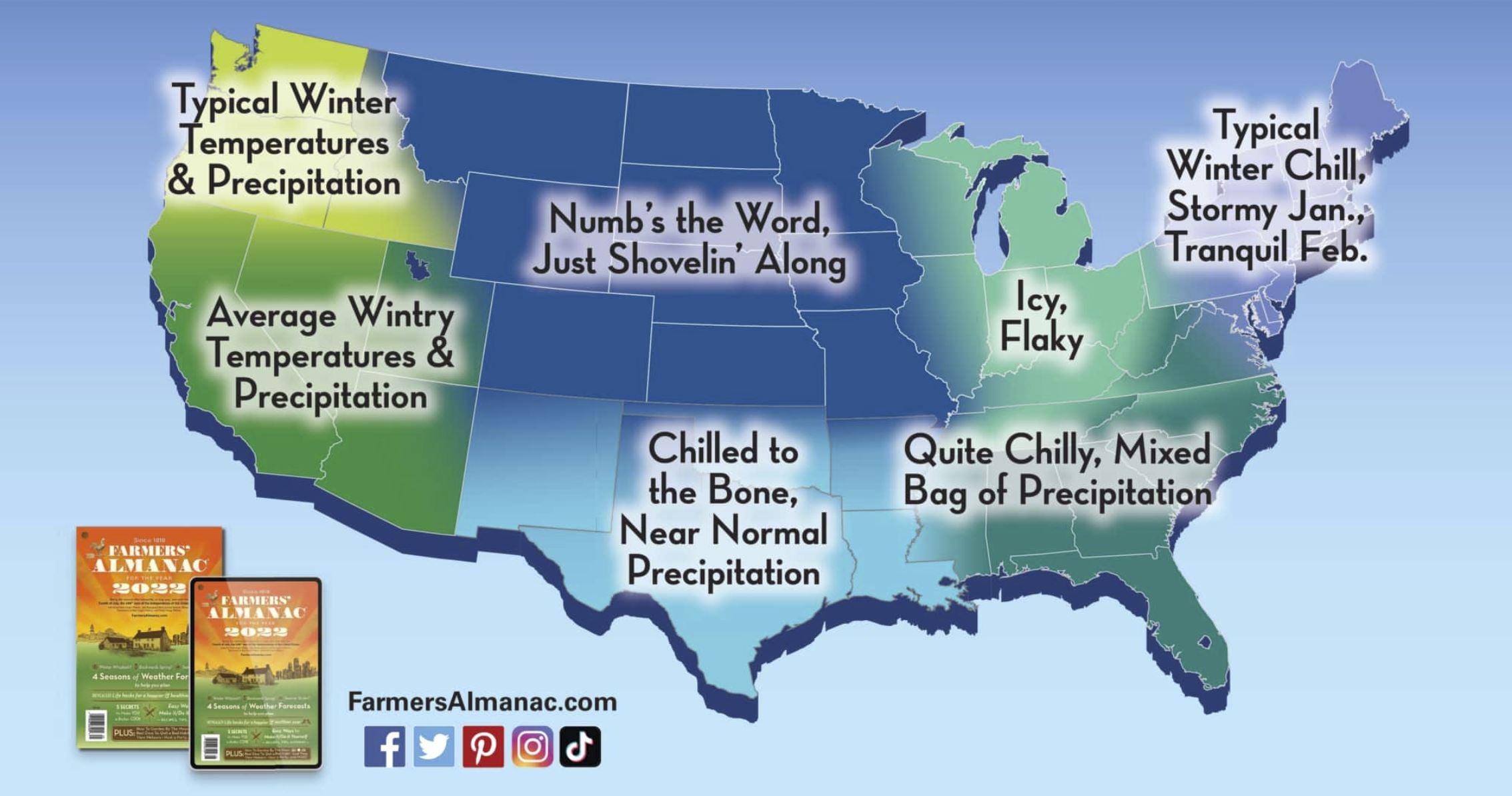

Both almanacs claim to have 80 percent accuracy in their predictions. Yet this accuracy may be a little too good to be true. Both almanacs make vague predictions like “higher than average snowfall” and “unusually cold January,” which gives them a bit of false accuracy. USA Today states that numerous media analyses show that neither the Old Farmer’s Almanac nor the Farmers’ Almanac gets it right — which shouldn’t be too surprising since most modern global technology doesn’t often predict more than a couple weeks out at any given time.

So maybe your harvest plans shouldn’t rely too heavily on what the almanacs are saying, but it’s up to you how you want to interpret the broad strokes of their predictions.

Even so, the almanacs provide much more than just weather predictions to their dedicated readers. Thomas, the original Old Farmer’s Almanac author, was a man with a good sense of humor, so he made sure to add jokes and riddles into his publication to keep his readers entertained.

Similarly, Britannica writes on its website that the Farmer’s Almanac contains weather, planting schedules, and “sundry pleasantries of rural humor.”

Along with the funny business is guides on planting schedules, tips on gardening, astronomical tables, recipes, and short articles on topics within agriculture. For only about $10, an almanac has a lot to offer. Most would even say that the non-weather related content is worth it, not matter how you feel about the weather reports.

Before you start your next season’s planning, would you fancy a look into an almanac, new or old? It might not be able to give you all the answers, but it will give you a few things to chew on, and a few new jokes to tell around the shop!

Elizabeth Maslyn is a Cornell University student pursuing a career in the dairy industry. Her passion for agriculture has driven her desire to learn more, and let the voices of our farmers be heard.