An official with the West Virginia Division of Highways says that Allegheny Wood Products International has not been approved to lease highway land designated for a timber fumigation facility in a Division of Air Quality permit evaluation — and furthermore, because the land is controlled access right of way, the highway division would not even be allowed to lease the property. This casts more doubt on whether the planned facility near Baker in Hardy County could reasonably be granted a permit without significant changes put in place.

The facility has raised concern in the community because of the site’s proximity to occupied dwellings and agricultural land. Timber fumigation of logs uses a highly toxic and ozone-depleting pesticide known as methyl bromide, which makes the logs less likely to transmit contaminants, particularly when shipped overseas.

After the Division of Air Quality published its intent to approve the facility’s permit in April, several red flags in the process — along with community pushback — have elevated the issue and sparked frank discussions about the health of nearby residents, livestock, and wildlife.

At a public meeting Thursday, Division of Air Quality evaluator Steven Pursley said that his permit would not trump local ordinance and that it would be denied if the chosen location was on someone’s property who has not granted a lease to the applicant. Confusion mounted after the address of permit application did not match the mapped location that Pursley listed in his intent-to-approve permit evaluation. Pursley conducted his review using Google Earth coordinates rather than visiting the site.

In an email dated May 8, Lee Thorne, District Five Engineer for the Division of Highways, wrote to Pursley saying, “Using the GPS coordinates provided in your attached letter and the WV Flood Tool, I have determined that the location is within the controlled access right of way for Corridor ‘H.’ … I can verify that the DOH has not been contacted regarding the lease of any of this right of way. Furthermore, since it is controlled access right of way, we would not be able to do so.”

While the location mapped in the permit evaluation is on highway land, the address listed in it is across the road on private agricultural zoned land on Park Farm Drive, which creates yet another barrier for the Allegheny Wood Products project to move forward.

According to Hardy County Planning Commissioner Melissa Scott, “The primary use of a property for activity centering around the use and storage of hazardous material for the treatment of products at the location is only permitted in industrial zones with conditional approval. No applications or inquiries have been made to the Hardy County Planning Commission or office for such approval.”

According to the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, human exposure to high concentrations of methyl bromide can cause central nervous system and respiratory system failures and can harm the lungs, eyes, and skin. In an email, the EPA said guidance has been “put in place to reduce potential exposure to bystanders, such as buffer zones, placarding, monitoring during treatment and aeration OR notification requirements, aeration buffer zones, and Fumigation Management Plans, which are described on the product labels.”

At the public meeting, Scott seemed unlikely to rezone the land even if an application to do so was received.

Hardy County has a population of about 14,000 and is located in West Virginia’s northeastern panhandle, bordering Virginia.

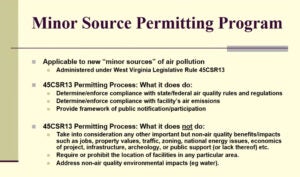

The permit for Allegheny Wood Products’ proposed facility said the company would use no more than 9.55 tons of methyl bromide per year, qualifying it as a “minor source” of air pollution. The threshold for becoming a “major source,” according to the Division of Air Quality, is 10 tons per year, which would open the company up to significantly more regulation. And because Allegheny’s proposed facility is several miles from a currently operating one on the other side of Hardy County, they are not considered contiguous, with permitting done separately for each location.

In email correspondence obtained by AGDAILY, Rex Tennant with S&J Environmental Services LLC, a division of Allegheny Wood Products’ legal counsel Steptoe & Johnson, says that the worst-case scenario for this facility would be using 100 percent oak logs, which would increase the annual discharge of methyl bromide to 10.608 tons. In a response, Pursley said that 80 percent oak could be assumed, which would lower the annual pollutant tonnage under the 10-ton threshold and avoid triggering the more stringent standards (a Maximum Achievable Control Technology review). He noted that the higher level, “At a minimum, it would delay issuance of the permit. At worst, AWP might have to install a control device.”

Tennant followed up with an email saying that he was informed that 80 percent oak logs is, in fact, the worst-case scenario for the site.

Pursley has said that the Division of Air Quality’s primary consideration is pollutant release, noting that human health, water quality, property values, economic impact, traffic patterns, and more are not allowed to be factored into the permitting approval process.

This statement drew the ire of the community during the public meeting, with some questioning what the purpose of the meeting was if public opinion and health can’t be considered by the agency.

The public comment period is open until the close of business on Friday, at which point the Division of Air Quality will make a final recommendation.

About 20 states regulate the use of methyl bromide in log fumigation, according to the Southern Environmental Law Center. According to Dr. Marshall White, an expert with Virginia Tech, the use of methyl bromide has been fully banned around many large population centers in Hawaii and Maryland, including the Baltimore region, which makes launching points such as eastern West Virginia a prime choice for timber companies readying their logs for overseas shipping.

Ryan Tipps is the founder and managing editor of AGDAILY. The Virginia Tech graduate has covered farming since 2011, and his writing has been honored by state- and national-level agricultural organizations.