The fast-paced nature of the modern U.S. beef industry can make it easy to forget just how far it has come over the course of our nation’s history. Today, for the most part, the system runs like a well-oiled machine. Science, genetics, and technology have allowed producers to home in on productivity and create a consistent end product. Some breeds have risen in popularity, and each has a national association guiding its organization and development.

Cattle are believed to have been on this continent since the late 1400s. Some of these first cattle were brought to the U.S. by explorer Christopher Columbus, yet were a far cry from the beef cattle we know today. Many were used for milk and meat, but efficiency and selective breeding weren’t necessarily at the top of anyone’s priority list, especially since most of the colonists were simply trying to survive. For example, in 1611, Plymouth pilgrims had a group of cattle and are recorded to have imported a bull and three cows from England. East of the Mississippi, cattle continued to spread, alongside immigrants, and beef became a protein staple for many. However, it is reported that for the most part, the demand for beef far outweighed the available supply.

In the West, cattle were brought into Texas from Mexico and generally roamed free. These Mexican cattle had been brought overseas by the Spanish. The first “ranches” are believed to have been established as early as the 1700s. In places like Arizona, periods of peace with the Apache tribes allowed for the establishment of more organized ranches, but that eventually fell apart — and when places were raided, cattle were let loose. Some of these cattle were captured by American Indians, and for example, it is believed that the Pima tribe raised cattle and used oxen. In California, cattle were a part of some of the Spanish missions.

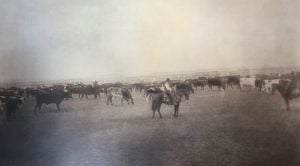

The Texas Longhorn, which is one of the most iconic images of the time, was spread across the plains by the 1800s. By 1830, there was said to be 100,000 cattle in Texas. The American cowboy was born from the desire to utilize these cattle. After the Texas Revolution in 1835 and 1836, cowboys gathered unbranded cattle, and they were declared the property of the republic of Texas. These southwestern cattle were wild, small, did not fatten well, and produced very little milk.

The gold rush and subsequent influx of settlers brought on a massive increase in the demand for food. In the 1850s, Eastern cattle were brought west, and in conjunction with the use of existing California cattle, beef production was increased. Getting beef from hoof to rail was an added challenge of the time, especially since all infrastructure was being built. Cold storage was not commonplace, so drying, curing, and salting were normal methods of preserving meat. Colonel Oliver Wheeler traveled to California from Connecticut and saw a need for a meat processor. He established a wholesale meat market in San Francisco and is one example of many entrepreneurs who saw this demand for beef as a business opportunity. As railroads and people spread across the West, beef followed.

The eastern U.S. still demanded beef, especially as the population increased, but it was difficult to get a product to these areas without refrigeration. A large number of cattle were butchered only for hide and tallow over these many years of development. The introduction of the refrigerated rail car in the 1860s completely revolutionized this issue.

Settlers were also finding their way north during this time. The first cattle drive from Texas to Montana took place in 1866. Miner Nelson Story, who had made his fortune in the gold fields of Alder Gulch, saw money in cattle and purchased a group of Longhorns in Texas. The number he purchased is unclear — most sources say 600 and others say more. Story was a resident of Bozeman and was most notably the town’s first millionaire. He hired a crew of cowboys to bring his cattle north. The drive was fraught with challenges — encounters with American Indians, flighty cattle, weather, and many other factors made this extremely challenging. The weathered crew of cowboys did make it to Eastern Montana, and many subsequent drives followed. Ranching soon became a part of places like Montana, and it was common for miners and businessmen to also invest in cattle. These drives established Texas cowboy culture in Eastern Montana, and to this day, the gear and methods used in this area are distinctly different than other western regions that had more influence from the Spanish vaqueros of California.

Establishing beef cattle in the north came with many challenges. Most famously, the blizzards of 1880 and 1881 killed around 50 percent of herds. This event did push the introduced Hereford genetics to the top, as they proved to be more hardy than their Shorthorn counterparts. The invention of barbed wire also revolutionized ranching, allowing for the enclosure of properties and better control over cattle.

During this time, stockyards were established throughout the country to centralize the market and help producers get fair prices for their cattle. For example, the Kansas City Stockyards were established in 1871 and didn’t close until 1991.

In addition to the wild Texas Longhorns of the west, specific breeds of cattle also found their place in the United States. The first “improved breed” to make its way to the U.S. was the Shorthorn breed in 1783. An attempt was made to cross Shorthorn cattle on Texas Longhorns, but due to fever ticks, most of the imported cattle died. The identification of diseases did help mitigate this, but introducing foreign animals to the established U.S. herds came with many health challenges. The Hereford breed was brought to the continent in 1817 by Henry Clay. By 1881, today’s American Hereford Association was established. The breed’s success and popularity ebbed and flowed with changes in beef production and the economy, but it still remains a vital part of the industry.

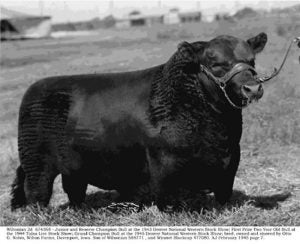

The Angus breed followed soon after, with George Grant importing four bulls to Kansas from Scotland. These first Angus bulls were crossed on Longhorn cows, which brought polled genetics into the U.S. beef industry. Over these early years, 1,200 Angus cattle were imported directly from Scotland, creating the base for the breed.

Surprisingly, the introduction of these breeds and crossbreeding pushed the original Longhorn into near extinction at one point. The U.S. Department of Interior allocated funds to preserve the breed, which became today’s Texas Longhorn breed.

The turn of the century brought about further advances in farming and ranching, and the beef industry continued to grow and improve. Research focused on beef cattle came about in the early 1900s, which began shaping the modern seedstock industry. Selective breeding within breeds like Herefords was taking place, which allowed for a vast improvement in the final product. Cattle size became moderate, and traits like milk and yield were focused on. World War II brought on an increased need for tallow, and a massive focus was put on fast-maturing cattle. This trend, like others in the past, went too far and the extremely stocky, wide cattle of the time came about.

This craze brought on many issues, including genetic defects like dwarfism. Cattle, like all species, have always carried genetic mutations, but the extreme focus that was put on specific traits took away diversity in genetics and stacked up the presence of these mutations in certain bloodlines. The Hereford breed was hit extremely hard by dwarfism. Today, any animal can be tested for known genetic defects before going into breeding, but at the time, the only option was to wait for the defect to be expressed, and then remove those bloodlines. Many breeders had to cull huge portions of their herds and essentially start over.

The industry learned many lessons from this time. The Red Angus Association was formed in 1954 as the first performance-focused breed association, and producers moved away from past extremes. In the 1950s, frozen semen was introduced, and while it took some time for Artificial Insemination (AI) technology to catch on, it was possible to further focus on top genetics.

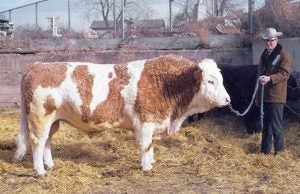

The late ’60s and early ’70s brought Continental breeds to the U.S. Various breeds were imported from Europe, and producers started crossing these breeds on their existing herds of Hereford and Angus cattle. Simmental is one of these breeds that made its way to America by boat. Travers Smith set out on a mission to find a Simmental sire to bring back to North America — and he imported “Parisien” in 1966. Smith had heard about the breed and believed it could revolutionize the beef industry. He traveled to France to find this red and white spotted bull calf and was able to import him to Canada for quarantine. The American Simmental Association was soon formed, and the breed was established in the country. Crossing this continental breed on existing British breeds made for massive increases in weaning weights.

Unfortunately, the industry hadn’t worked all of the fads out of its system, and by the 1980s, beef cattle frame size had exploded. This brought with it a variety of problems, including large birth weights. Many veterinarians of the time despised Continental breeds like Simmental, as the hybrid vigor they added hadn’t been controlled in a way that kept calf birth weights down. The American Angus Association and other associations stepped in to resolve this issue and also focused on producing seedstock that could help commercial producers raise calves that feeders and packers wanted. During this time, different factions of the beef industry emerged, as show cattle, performance cattle, and club calves separated for the most part.

Today, genetic technology, data collection, and performance measures guide the seedstock industry and allow commercial producers to select genetics that are the most suited for their environment. The Angus breed continues to dominate the industry, and black-hided cattle are the most common. However, crossbreeding continues to increase throughout commercial operations, and crosses like SimAngus (Simmental/Angus) and Angus/Hereford (black baldy) are popular. Genetic selection today is so fine-tuned, that in the hot, fescue regions of the country, producers can select for cattle that will succeed in these environments. Capitalizing on the best traits of multiple breeds allows commercial producers to have cattle with low birth weights, large weaning weights, good carcass traits, hardy immune systems, and, overall, produce a profitable product.

Looking back at the gangly Texas Longhorns and oddly-shaped Shorthorns of the U.S. beef industry’s early history, it is quite incredible to see how precise and efficient cattle are today. Beef has been a source of protein for this nation since its early days and will continue to be into the future.

Lilly Platts lives in Montana, where she is an editor at the American Simmental Association and writes freelance pieces for a number of ag publications.