DAILY Bites

-

Recycling excreta could meet 13% of crop nutrient needs and cut fertilizer imports significantly.

-

This approach promotes sustainability by reducing pollution from nutrient runoff into water sources, such as harmful algal blooms, and helps establish a circular economy between food consumption and agriculture.

-

Addressing public perception challenges and leveraging this recycling method can enhance global food security for a growing population.

DAILY Discussion

Recycling human and animal excreta has the potential to significantly reduce the need for traditional mineral fertilizers while supporting global crop production, according to a study published in Nature Sustainability. This innovative approach could alleviate dependency on mined phosphorus and fossil fuel-intensive nitrogen fertilizers, advancing sustainability in agriculture.

Johannes Lehmann, the Liberty Hyde Bailey Professor in the School of Integrative Plant Science at Cornell University and the study’s senior author, emphasized the importance of resource efficiency.

“We have to find ways to recycle the nutrients that are now poorly utilized, and our data shows that there is a lot of it: Many countries could become self-sufficient at current fertilizer use if they would recycle excreta to agriculture,” Lehmann said.

Led by doctoral student Mariana Devault, the research team conducted an extensive analysis using datasets from sources like the United Nations Food and Agricultural Organization and the International Fertilizer Association.

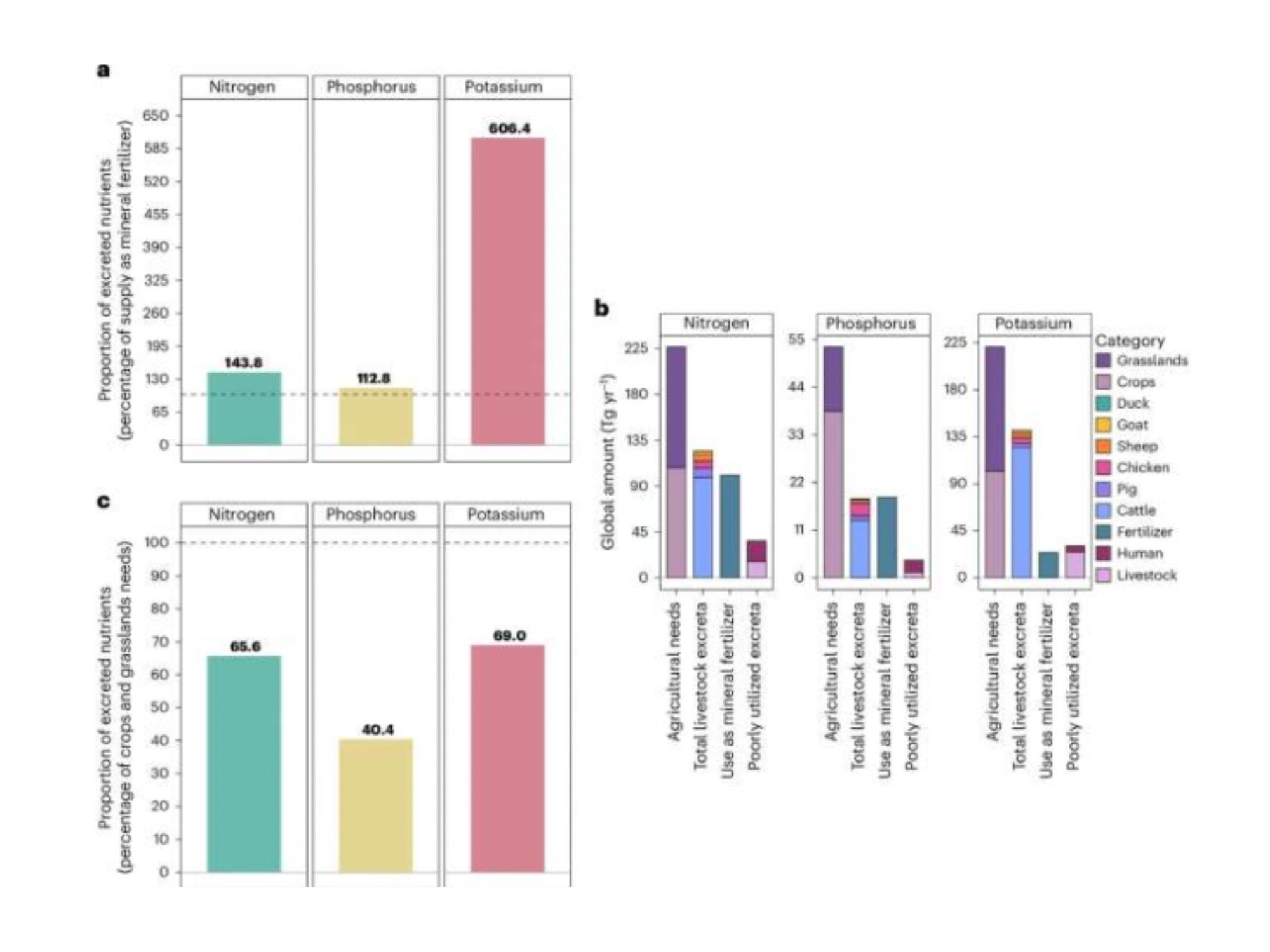

The study examined the locations and quantities of nutrients from human and livestock excreta and modeled their potential impact if recycled into agricultural systems.

The results are promising: Globally, the nutrients found in human and underutilized livestock excreta could meet 13 percent of the nutrient demands of crops and grasslands. National-level recycling could reduce global net imports of nitrogen by 41 percent, phosphorus by 3 percent, and potassium by 36 percent. Beyond meeting nutrient demands, this practice could mitigate nutrient runoff into water sources, reducing pollution and phenomena such as harmful algal blooms.

Lehmann highlighted the geopolitical implications of fertilizer dependency, comparing it to the oil crisis. With phosphorus sourced from a limited number of countries and nitrogen production requiring substantial energy, recycling offers a pathway to resource independence and environmental stewardship.

“The basic fact is that any nutrient that we remove in agriculture, and we obviously remove a lot, we have to replenish. There’s no free lunch,” he said.

Despite the potential benefits, challenges remain, including public perception. Using fertilizers derived from human waste may require cultural shifts, but Lehmann argues that closing the nutrient loop is critical for a growing global population.

“There are many countries in the world that flush down more nitrogen in the toilet than they import or add as agricultural fertilizer on their lands, and I think that’s a crime,” he said.

As the world’s population approaches 10 billion by 2050, establishing a circular economy between food consumption and agriculture could be key to ensuring food security while protecting natural resources.