Outside a bar in southern Arizona in 1890, a stagecoach driver stumbled into the night and fell asleep in the open air, unknowingly becoming host to hundreds of screwworms while passed out drunk. The parasitic insects made their way through his nose, into his throat, and eventually killed him — a grim but once relatively common occurrence.

This chilling account of myiasis (or parasitic infection of fly larvae) was shared by Dr. Gary Thrasher, a veterinarian who recounted the story to AGDAILY after reading Borderland Chronicles No. 62, a publication by Douglas historian Cindy Hayostek. Douglas was once a pivotal distribution hub for sterilized male flies used in screwworm eradication efforts. Now, U.S. livestock producers and animal health professionals are again finding themselves on high alert.

In June, Costa Rica reported its first human death attributed to the New World screwworm (Cochliomyia hominivorax) infection since at least the 1990s. While screwworms primarily affect animals, this fatality — linked to an infestation in a person with a disability — was the seventh confirmed human case since the pest’s return to Costa Rica in 2023.

In 2017, New World screwworms were eradicated again after an infestation in the Florida Keys that likely blew in on a storm, killing about 135 endangered Key deer.

Thrasher, known to most as “Doc”, is a respected rancher and veterinarian who played a key role in screwworm eradication campaigns in the American Southwest of the 1970s. Over his decades-long career, he has operated ranches, owned a veterinary clinic, and made essential contributions to livestock health programs, such as brucellosis, tuberculosis, and screwworm eradication programs.

The recent re-emergence of the New World screwworm in the southern region of Mexico and Central America — where it had been eradicated for many decades — has caused renewed alarm among veterinary and agricultural communities across the United States.

New World screwworm, a parasitic flesh-eating fly, despite its past eradication during the 20th century in the U.S. remains a notable threat to livestock, wildlife, pets, and even human life. The trend at present suggests that the infestation could return to the Southern United States.

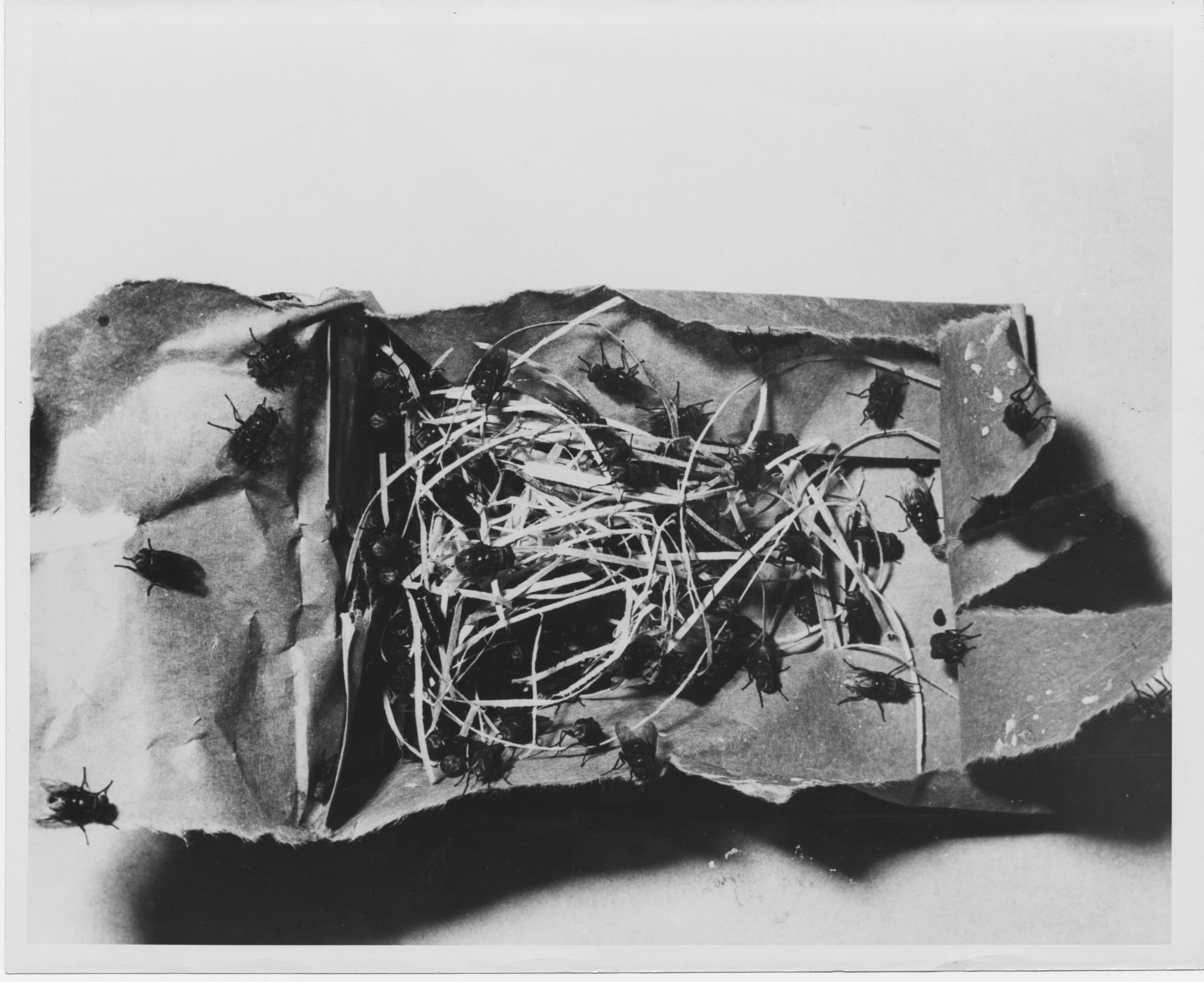

Screwworm infestations plagued the United States during much of the early part of the 20th century. The hundreds of eggs that female screwworm flies lay on open wounds or mucous membranes of warm-blooded animals hatch to become larvae, which burrow into living tissue to cause immense destruction, secondary infection, and generally death.

Cattle were the primary victims, but pets, wildlife, and humans were not immune. Most reports said that cattle could die as quickly as 10 days after infestation.

The larvae mature in five to seven days, dropping to the ground to pupate into adult flies. Female flies live two to three weeks but mate only once in their lifetime. In endemic areas, animals must be inspected every few days to detect early infestations.

Treating livestock infested with screwworms was an unpleasant and labor-intensive task. Ranchers had to frequently inspect animals for infested wounds, which required immediate treatment and confinement. Early treatments ranged from pine tar oil to foul-smelling insecticidal smears. Despite these types of efforts, screwworms were pervasive — in one instance, they caused the deaths of 180,000 livestock in less than half of Texas counties in 1935.

Native to the Southwest, screwworms spread to the Southeast in 1933 when infested livestock were unknowingly transported to the region.

By the late 1930s, significant progress had been made in controlling the screwworm problem. Researchers had established the screwworm as a particular species needing live hosts in order to live. This understanding was instrumental in developing specific control strategies.

Thrasher, who operated in the 1970s throughout New Mexico, Texas, and Nevada, recalls the severity of the problem.

“In 1978 alone, Texas reported 90,000 cases of screwworm infestations,” he explained. “Arizona had fewer cases, but the impact was still significant.” Ranchers and veterinarians faced an uphill battle, often losing livestock despite their best efforts to control the infestations.

The smell of screwworm infestation, though, is something that Thrasher says he could immediately detect.

“Back in the day, there were plenty of people who had cow dogs that learned how to smell the sweet smell of screwworms, and the dogs would find the cows and calves with screwworms,” Thrasher said.

Combatting the crisis

To mitigate the damage, the entire cattle industry adapted its practices. Thrasher notes how calving, branding, and castration schedules were moved to early spring to avoid screwworm season. This shift reduced the numbers of open wounds in animals when screwworms were most active, cutting the risk of infestations.

Key advances came in the 1950s from the scientists Edward F. Knipling and Raymond C. Bushland. Bushland developed a system for raising enormous numbers of screwworm flies in controlled conditions, a necessity before any large-scale operation could take place. Knipling, meanwhile, studied the species’ mating behaviors and formulated a revolutionary theory: controlling the pest population by releasing sterilized males to disrupt reproduction. (The colleagues won the World Food Prize in 1992 for their efforts).

Despite these breakthroughs, one critical piece of the puzzle remained elusive — a reliable way to sterilize large numbers of screwworms. Without this capability, implementing Knipling’s approach was not yet feasible, leaving the pest’s eradication an ambitious goal rather than an imminent reality.

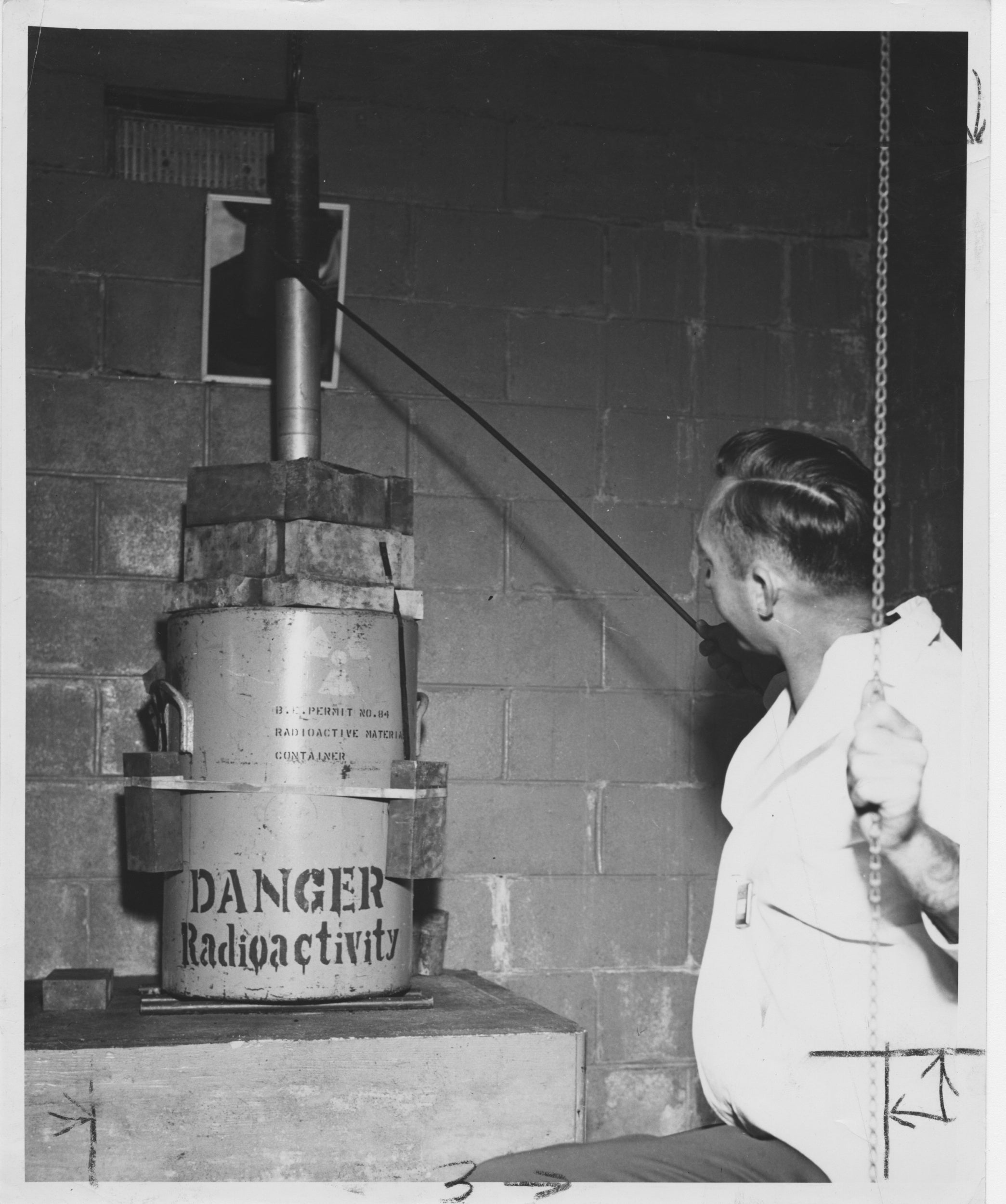

Eventually, thanks to their groundbreaking Sterile Insect Technique, the United States claims to have eradicated screwworms in 1966. Male screwworm flies were sterilized using cobalt-60 radiation and released en masse to mate with wild females, disrupting reproduction cycles and collapsing the screwworm population. The sterile flies are an effective form of control because a female screwworm fly mates only one time.

Thrasher, however, challenges the official timeline for eradication, citing personal experience and historical records.

“They claim eradication happened in 1966, but that’s misleading,” he said. “We were still dealing with tens of thousands of cases in the late 1970s. In 1978, Texas had 90,000 cases — that doesn’t sound like eradication to me.” A year later, the announcement came that one of the facilities would be closed after a historic freeze.

The sterile flies used in the eradication efforts were transported in small, white boxes marked with bright red radiation symbols and warnings not to touch. “They actually flew the sterilized flies out of Douglas in the first six months of 1980, often in C-45s,” Thrasher said.

“Each box contained thousands of sterilized flies, and the boxes were designed to release the flies in targeted areas,” he added. “People often panicked seeing the radiation labels, especially when boxes were accidentally dropped near homes or public areas.”

The U.S. Department of Agriculture recorded that the severe winter of 1957-58 forced screwworms into a smaller overwintering area than usual. Seizing the opportunity, sterile male flies were rapidly released in early 1958 to establish a barrier zone across central Florida. Throughout that year and into 1959, sterile flies were air-dropped in heavy, and then gradually lighter, concentrations across three zones in Florida.

By the end of 1959, sterile fly releases had eradicated screwworms from Florida and the Southeast ahead of schedule. The region remained screwworm-free through rigorous livestock inspection, quarantine practices, and occasional concentrated releases of sterile flies in areas where accidental reinfestation occurred due to imported livestock from other regions.

The focus of eradication efforts shifted to the Southwest in 1962, supported by funding from southwestern livestock producers, the Southwest Animal Health Research Foundation, the federal government, and the state of Texas. Sterile fly production was ramped up at ARS laboratories in Kerrville and Mission, Texas, to address the challenge.

The Southwest program covered a significantly larger area than the Southeast and faced the persistent risk of reinfestation from Mexico. The strategy combined mass releases of sterile flies with active participation from livestock producers. Producers were essential in treating wounds on animals both before and after infestations occurred.

Additionally, they collected eggs and larvae from infested animals to send to USDA laboratories, enabling scientists to monitor the program’s effectiveness across the vast region. This data guided the release of sterile flies, allowing targeted responses to outbreaks and hotspot areas.

Eradication programs extended southward, with cooperative initiatives between the United States, Mexico, and Central American countries. Scientists introduced various innovations, including the Screwworm Adult Suppression System (SWASS), which combined screwworm fly attractants with insecticide pellets. By 1982, screwworms were effectively eliminated from northern Mexico, also marking the last year Texas reported an infestation.

In 1983, a new facility in Tuxtla Gutiérrez, Chiapas, Mexico, began producing 500 million sterile flies weekly. This moved fly production closer to the advancing barrier zone as eradication efforts pushed the screwworm population farther south.

The Mexico-United States Screwworm Eradication Program initially contemplated the establishment of a permanent barrier zone along the Isthmus of Tehuantepec, the narrowest land strip between the Gulf of Mexico and the Pacific Ocean. By the mid-1980s, however, authorities understood that extending eradication to a biological barrier provided by the Darién Gap in Panama would establish a wider and more permanent solution.

Modern feasibility of such operations has diminished due to increased urbanization and public resistance to radiation-related programs.

“You can imagine the outcry today if planes were dropping boxes with radiation symbols over populated areas,” Thrasher noted. “While the technique was highly effective, the logistical and public relations challenges would make it much harder to implement today.”

In 1993, Mexico recorded the era’s last screwworm outbreak.

The newly emerging threat

This past November, the live cattle trade between the U.S. and Mexico was halted after a cow in Chiapas, Mexico, was found with New World screwworm myiasis. Officials note that trade will only resume with stringent NWS mitigation protocols, including preventive treatments and multiple inspections on both sides of the border.

Thrasher expressed concern about the challenges posed by warming temperatures that would allow screwworms to move farther north, and modern ranching practices.

“With fewer hands to manage large herds, early detection is harder,” he explained. Injectable ivermectin and topical treatments remain effective but require frequent reapplication, and re-establishing sterile fly programs could face logistical and public resistance.

The reintroduction of screwworms would have catastrophic consequences for agriculture. The Southwest’s cattle industry, heavily reliant on interstate and international trade, would be severely disrupted.

“Most Arizona beef calves are shipped to feedlots in other states,” Thrasher noted. “If screwworms reappear, restrictions on livestock movement will cripple the market. The cattle industry in Arizona relies heavily on the ability to export calves to finishing operations in Texas, Kansas, and beyond. If we lose that ability due to border shutdowns or interstate restrictions, the economic fallout could be immense.”

Thrasher explains that the USDA is collaborating with the Mexican government to implement pre-inspection stations where cattle are processed under strict protocols, including ivermectin treatments. Once this initial phase is complete, the cattle undergo a second inspection and are transferred to more rigorous inspection corrals for dipping and comprehensive health evaluations.

These pre-inspection stations already feature corrals that function as initial checkpoints, where smaller groups of cattle are assembled, tagged with individual ID tags, and subjected to preliminary procedures, such as TB testing. However, at the time of the interview, Mexico had not fully responded yet.

Roughly 1.25 million cattle come in to fill up about 5 percent of U.S. feedlots.

Pets and wildlife are equally at risk; Thrasher recounted a case involving a dog that traveled between Arizona and Mexico.

“The dog had screwworms between its toes,” he said. “It’s a clear example of how easily they can spread.”

Another control issue, Thrasher noted, is that the Darién Gap, which was once an excellent stopgap for screwworms with dense jungles, “is now a super highway for migrants. And, there are thousands of people tromping through that jungle every day now, and people can bring it too.”

In December, the USDA’s Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service released $165 million of emergency funding to fight the threat. The funds support surveillance, animal health checkpoints, and cooperative programs with Mexico and Central America to rebuild biological barriers.

Veterinary vigilance remains the first line of defense. Infestations are identified through close inspection of wounds, which show drainage, discharge, and the presence of larvae. The odour of necrotic tissue typically denotes advanced infestations. Owners and producers are asked to report suspected cases to state or federal authorities at once.

National Cattlemen’s Beef Association chief veterinarian Dr. Kathy Simmons highlighted the importance of early detection in maintaining outbreaks in check. Veterinarians have a critical role to play in protecting livestock and wildlife.

“Although we haven’t confirmed any New World screwworms in the United States, we need you to be on high alert. New World screwworms have orange eyes, a metallic blue or green body, and three dark stripes across their backs. If you see any suspicious flies, please alert your local veterinarian, extension agent, or contact USDA-APHIS Veterinary Services,” wrote Kim Brackett, the Policy Division Chair of the National Cattlemen’s Beef Association.

As the screwworm continues to spread across Central America, veterinary and agricultural communities in the United States are increasingly concerned about its potential to re-establish itself north of the border.

Update 1/17/2025: The article was updated to include a reference to Southern Arizona, where a Florence stagecoach driver was killed by screwworms in 1890.

Heidi Crnkovic, is the Associate Editor for AGDAILY. She is a New Mexico native with deep-seated roots in the Southwest and a passion for all things agriculture.