One family’s dedication to bringing fine quality, source-verified ‘Made in the USA’ Merino wool to Americans is paying off

For fourth-generation rancher Evan Helle in Dillion, Montana, managing thousands of sheep on his family-owned 25,000-acre Helle Rambouillet (ram-boo-ley) Ranch is in his blood. And it’s tradition. What his great grandfather saw decades back in the wild west, Helle sees now — thousands of white Rambouillet sheep grazing on forbs and wildflowers across a vast meadow.

In the 1930s, Helle’s 13-year-old great grandfather sold the family car to buy the ranch’s first Rambouillet sheep. What started out of necessity to support his mom and younger brother (after the passing of his father) is now a flourishing sheep ranching operation with a strong land-stewardship heritage.

“We’re taking care of the land,” said Evan Helle. “That’s our job.”

Although the family’s sheep still graze Montana fields as in days gone by, some things have changed over the years for the Helle family. They’ve embraced technology by integrating fiber analyzers and electronic trackers into their ranching operations. They’ve teamed up with range scientists to ensure sustainable grazing. And they’ve co-founded a modern apparel company, Duckworth, where they offer the world’s only source-verified single origin Merino wool textiles like performance base layers, vests, socks, hoodies and coats — all of which come with a 100 percent made in the U.S. guarantee.

Wool as a commodity

Wool is one of the oldest trade commodities known to man. People in ancient civilizations hand spun wool, vikings in the Middle Ages used wool for the sails of their longboats, and after the invention of the spinning wheel circa 1030, wool textile production became commonplace. Then came mass production. U.S. factory owners struck it rich in the 18th century during the Industrial Revolution as the wool industry boomed.

“During World War II, wool was heavily used for war efforts like clothing soldiers,” said Brent Roeder, an extension sheep and wool specialist at Montana State University. “By 1945, the U.S. had about 50 million head of sheep.”

Today, most of America’s wool is imported from countries like Australia, China, and New Zealand. And U.S. sheep numbers have fallen nearly 90 percent since 1945. According to the latest numbers by the U.S. Department of Agriculture, there are about 5 million head of sheep in the U.S. — a number similar to the population of South Carolina.

“It’s due to a number of factors,” said Roeder, who mentioned market fluctuations and fads that influenced people to switch to newer (and cheaper) fabrics like polyester, nylon, and rayon. He also said a lot of sheep farmers switched to cattle ranching as it became more profitable with improved infrastructure. But one unique psychological stigma of sheep — stemming from the war — could’ve also contributed to declining sheep numbers in the U.S..

“My great uncle fought in WWII and he ate a lot of canned mutton in the trenches, which is a pretty bad way to serve lamb — cold with a lot of fat,” said Roeder. “When soldiers returned home, the smell of lamb was known to trigger post-traumatic stress disorder, so a lot of men that served in the war forbid their families from cooking lamb.”

“Overall, sheep farming in the U.S. is an interesting dynamic,” added Roeder. “I don’t know if anyone has really put their finger on it. But we’re starting to see a lot of interest in younger generations to go back to locally sourced, sustainable high-quality products. There’s a big shift happening.”

Helle Rambouillet Merino wool

Rambouillet is the French version of Merino developed when Louis XVI imported a few hundred Spanish Merinos in the late 1700s for his estate at Rambouillet. Though named for the town in France, the breed owes much of its development to Germany and the United States.

Certified Rambouillet wool is a luxury, bringing ranchers a premium price at market. It has fine fibers, a natural stretch and it’s incredibly soft — making that thick itchy heavy-duty sweater your grandfather wore a thing of the past. Some small sheep farmers even sell their Rambouillet wool to artisan crafters on Etsy for $70 a pound or more.

The extreme Montana temperatures help the Helle Ramouillet flock produce a very highly sought-after dense crimp (the natural waviness of the wool fiber) that’s almost like a spring. The crimp traps air and helps keep the sheep warm. It’s also why their wool has higher amounts of stretch to it than other wools.

“We have a pure-bred flock that we keep genetic records for,” said Helle, referring to his family’s Helle Rambouillet flock. “The ram lambs [or males] from that flock are what we keep for breeding.”

Embracing modern technology

For the Helle family, keeping their pedigree heritage is important. But keeping data up to date for a pure-bred flock when you’re tending to thousands of sheep each year requires a lot of work. It also requires a lot of attention, and lot of data collection.

“Data collection and selective breeding are two of the biggest breakthroughs for us,” said Evan Helle, who uses modern technology to determine wool grade and track the flocks.

Twenty years ago, the Helle family started using Optical Fiber Diameter Analysers (OFDA), developed by Australian engineers in the early 2000s.

“There’s only a few OFDAs in the U.S.,” added Helle who said the machine is operated by a technician from the Montana State University’s wool lab at their ranch. The technician scans a piece of wool with a computer scanner and retrieves important data, like length and quality.

“The most innovative thing about the OFDA is that we get real time data that allows us to make decisions seconds after the sheep are shorn, which allows us to make the most informed marketing decisions about our wool,” said Helle.

“Before this technology, we had people trained as wool classers. They would just look at the wool, feel it and determine its grade. Now, the grade is data driven. The technology and the science behind it improve the grading process.”

Along with those measurements, Helle records how many lambs each sheep has in its life (which is about eight to nine lambs weaned over an ewe’s lifetime which is typically seven to ten years). He also records each lamb’s weight, fleece weight, yearling weight and how fast it grows.

“All this data basically boils down to giving us the estimated breeding Value, or EBVs for each sheep based on the probability and percentage of all of these characteristics,” said Helle.

And that’s why affixing electronic identification trackers (or EIDs) to each sheep’s ear is crucial — a practice the Helle family has done now for the past five years. When you’re tending to 5,000 to 8,000 sheep (or 5 to 8 “bands”) every year, having every ram, ewe and lamb microchipped saves ranch hands both time and labor while increasing information accuracy.

Combined, these modern technology advances are critical to both quality control and growth for the Helle family.

Sustainable grazing

Sustainable grazing practices are not only crucial to the quality of merino wool each Rambouillet sheep produces, but they’re also important for maintaining a healthy ecosystem.

The 1989 United Nations (UN) report “Our common future” raised global awareness of overuse of natural resources and led to the further development of the concept of sustainability. Over time the UN expanded this notion of sustainability to include social, environmental and economic sustainability, as the balance of the three ensures the sustainability of a product, company, supply chain or sector. For the Helle’s — sustainable grazing supports the wool industry as a whole.

Every year at the Helle Rambouillet Ranch, sheep herders drive several bands of sheep up 60 miles into the mountains around June so they’re flocks can graze on public land in the Beaverhead Deer Lodge National Forest. Each band of 1,000 sheep has two sheep herders, two horses, a few livestock guard dogs (like Great Pyrenees to deter predators such as coyotes and bears), and a handful of trained border collies to herd the sheep.

“It’s a unique lifestyle,” said Helle. “The sheep herders live with the sheep 24/7 from June to October, often living out of old sheep wagons.”

And with the help of U.S. Forest Service range scientists, the sheep herders know where, when, and how long to graze each band of sheep on public lands.

“Working with the range scientists prevents overgrazing,” said Helle. And since sheep are mostly browsers, preferring forbs and wildflowers over just eating all the grass, they have different grazing patterns than cattle — making their grazing patterns complimentary to cattle. And sometimes the Helle’s sheep graze cattle pastures before the cattle arrive. “The sheep seek out and eat all the Larkspur plants; delicious and harmless to sheep but deadly and toxic to cattle,” said Helle, so it’s a natural way to avoid cattle deaths when there’s a big bloom of Larkspur.

“You can run about 100 sheep per every 500 cows without changing your sustainability,” added sheep and wool specialist Brent Roeder. “The type of nutrition doesn’t change or the grass they eat which is good for business on the American wool production side. Just like farm to table, people want to know where their wool comes from. And they want to know it’s a sustainable practice.”

Duckworth clothing

For the Helle family, all their innovations and extra work on the ranch needed to mean something. And they grew tired of getting commodity-type pricing for their premium wool.

It was partly that frustration seven years ago that inspired Evan Helle’s dad and third-generation rancher, John Helle to co-found Duckworth, the world’s only source-verified single origin Merino wool apparel company.

“All of the wool used in Duckworth clothing is 100 percent made in the U.S. from our very own Rambouillet Merino flock,” Helle said. “And more recently, a handful of certified Duckworth growers are contributing to keep up with the growing demand.”

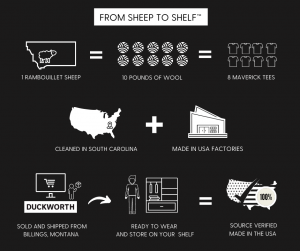

“Sheep-to-shelf is the cornerstone of the whole operation,” said Duckworth’s marketing manager, Mike Somerby. And it’s just that. From sheep-to-shelf. A sheep is shorn on the Helle Ranch in Montana, and it ultimately becomes a garment on someone’s shelf.

“That fiber never leaves the USA,” added Somerby. “The single-origin, source-verified nature of our wool ties it all together.”

Once the wool is shorn, the Helle family sends it to South Carolina to be cleaned. Factory workers first scour the wool by dipping it into a 100-foot-long-soapy water bath. Then it gets carded, combed, baled, and turned into “Top” (a continuous strand of manufactured wool). From there, the Top is sent to multiple U.S. factories to be spun, knitted, dyed, finished and cut by factory workers — turning the wool into performance base layers, vests, socks, hoodies, coats and more.

“One sheep yields about 10 pounds of wool,” said Even Helle. “Which makes about eight Maverick Tees or 15 Vapor Tees. The difference stems from fabric weight and wool percentage.”

The Helle family runs Duckworth with the same salt-of-the-earth ethics as their ranch.

“We’ve spent a painstaking amount of time developing our proprietary yarns and fabrics, making our apparel totally unique, but also of the highest quality because we manage every step,” said Somerby.

“It’s how we like to do things and relates to our role as stewards of the land on which our animals graze and upon which we base our livelihood.”

One of Duckworth’s top sellers is their wool-blend Vapor shirt — designed by a textile specialist that acts sort of like blotting paper on your skin.

“The designer was in many senses a mad scientist rendering the very best out of the natural properties of wool — odor-free (antimicrobial, moisture wicking, durability, softness, etc.),” said Somerby. “It’s due to those efforts that our fabrics are really industry standouts.”

For a lot of people, wearing wool all year round is a foreign concept. “People just don’t associate wool as a cooling fabric,” said Roeder, who has several Duckworth pieces. “I’ll wear my Duckworth Vapor shirt down in Texas in August, and I’ll use it as a base layer here in Montana in the winter. It’s really pretty versatile.”

The Helle’s sold their first “Sheep to Shelf” wool product through Duckworth in 2014. And over the past six years, sales continue growing on a noteworthy basis year over year.

“Keeping up with demand has been tough,” said Helle, who said they had to change their sales model when the pandemic hit in March 2020.

“Before COVID, we sold about 50 percent of our Duckworth inventory to store owners,” he said. “But most of our orders were canceled. We shifted our sales focus online. It takes a whole different skill set, but we’ve been growing really fast.”

As Duckworth’s customer base grows, word of mouth has followed. Sales continue to rise, and the Duckworth Instagram page has more than 12,000 followers

For Evan Helle, being a part of producing sustainable, natural and quality products for people to use just makes sense.

“People really appreciate the simplicity of it,” he said. “And the fact that I can wear a shirt I know came directly off of our ranch is pretty rewarding.”

Facing down challenges

• Agricultural challenges: One of the biggest challenges for the Helle family is predators. “We’ll lose anywhere from 10 to 15 percent of our flock each year due to weather and predators like coyotes, bears and wolves,” said Evan Helle. “Without the guard dogs that number would be substantially more, but it’s still a big challenge for us.”

• Duckworth challenges: Keeping up with demand continues to be a challenge as sales increase. And adding more print or pattern options to their Duckworth line has its own challenges. “We’ve looked a few places here in the U.S. to produce different prints, but most factories are only designed to print polyester,” Helle said. “There’s just not that many that dye wool since it takes a special type of dye, but we’re definitely looking into it.”

Suzanne Downing is an outdoor writer and photographer in Montana with an environmental science journalism background. Her work can be found in Outdoors Unlimited, Bugle Magazine, Missoulian, Byline Magazine, Communique, MTPR online, UM Native News, National Wildlife Federation campaigns and more.