The veterinary industry is facing a crisis, particularly in rural America, where farmers and ranchers struggle to find large-animal veterinarians. Since the end of World War II, the United States has lost 90 percent of its large-animal and livestock veterinarians, according to a 2023 Johns Hopkins study. As the shortage worsens, some areas are left with little to no veterinary coverage for miles, putting the health and welfare of livestock at risk.

According to 2023 data from the American Veterinary Medical Association, the number of mixed and food animal veterinarians fell by 15 percent. While 68,000 veterinarians were working in small animal practices, just over 8,000 were working in large animal or mixed practices.

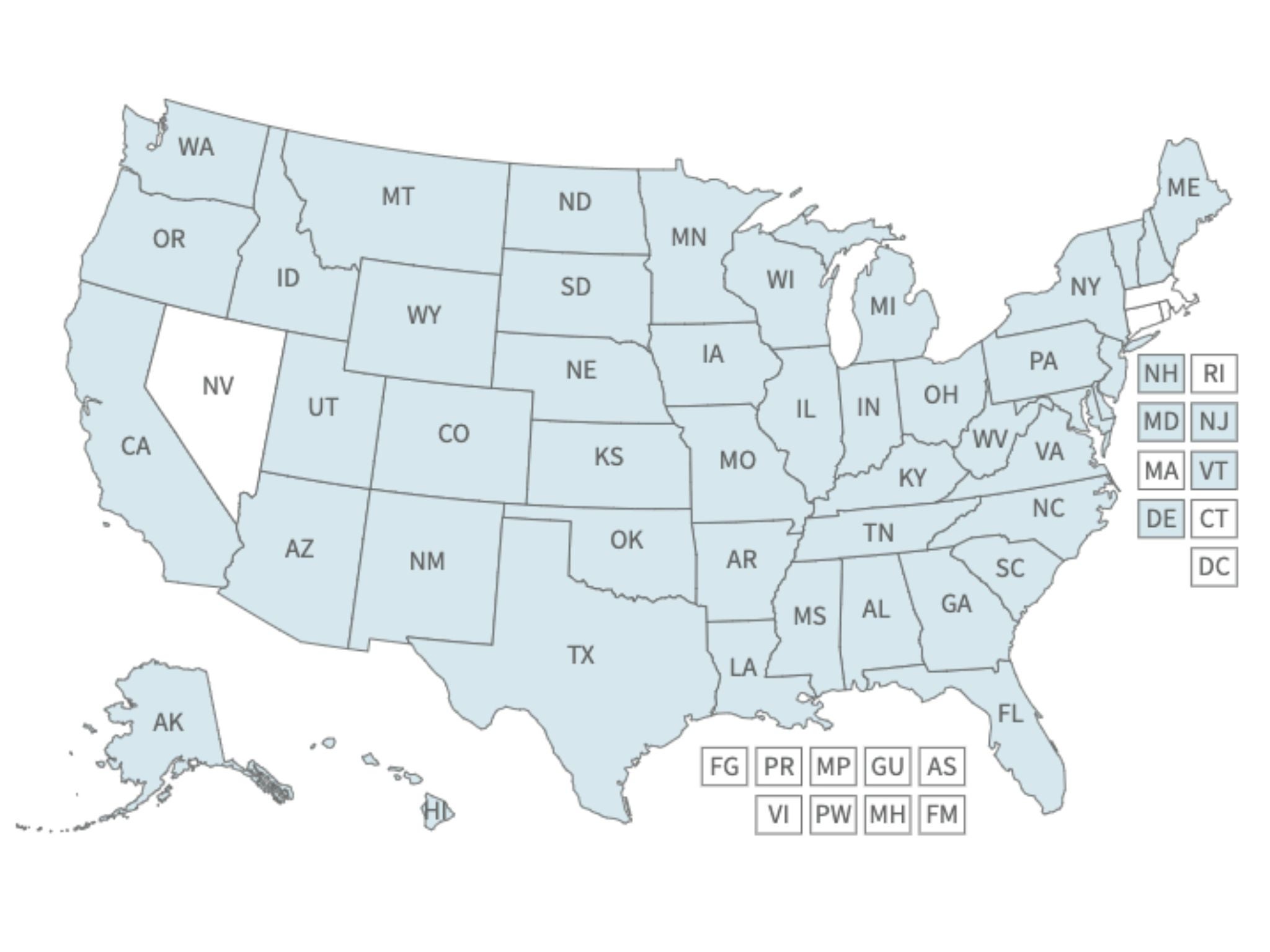

The U.S. Department of Agriculture’s National Institute of Food and Agriculture keeps track of shortages on their Veterinarian Shortage Situation map, which contains all shortages in a fiscal year. All of the states in blue have at least one designated shortage area. In 2024, the biggest number of shortages were in the Midwest, West, and Georgia. Of the states with shortages, the AVMA says that beef cattle are consistently the species with the greatest need.

This isn’t just a minor inconvenience; it’s a serious threat to animal welfare, food security, and the future of agriculture.

Why is there a shortage of large-animal vets? Well, there are several reasons:

1. Financial barriers: The cost of veterinary school is staggering, often leaving students with hundreds of thousands of dollars in debt. Research.com explains that in-state veterinary students typically pay $78,479 to $155,295 for the entire four-year program, while out-of-state students spend $131,200 to $285,367.

Salaries for large-animal veterinarians are generally lower than those of small-animal practitioners, particularly those working in high-end urban pet clinics. While the lowest mean salary in 2024 for mixed animal and equine veterinarians was about $100,000, the mean salary for companion animal veterinarians was about $133,000. As a result, many new graduates, burdened with significant student loan debt, may opt for companion animal practice over livestock care.

As a result, over the past decade, the number of companion animal veterinarians has risen by 22 percent, while the number of mixed-animal and food-animal veterinarians has declined by 15 percent. In fact, an American Association of Bovine Practitioners exit surveys show that most veterinarians who leave cattle practice transition to companion animal medicine

2. Challenging working conditions: Larger-animal veterinarians often work unpredictable and long hours. You never know when an emergency could strike, and responding to a distressed cow at 3 a.m. in the middle of a snowstorm isn’t exactly an appealing career perk. The physically demanding nature of the job, coupled with exposure to harsh weather and dangerous animals, can lead to burnout.

But it’s not just the physical demands. Suicide rates for veterinarians have been a topic of conversation in the recent decade. Merck Animal Health completed a study on veterinary well-being. Of the 4,634 veterinarians surveyed, only 2 percent identified as food animal veterinarians.

Food animal veterinarians differ from their counterparts in several key ways, including demographics, work hours, and career satisfaction. They are more likely to be male, live in rural areas — particularly in the Midwest — and include a larger representation of both Baby Boomers and Generation Z. They also work 25 percent more hours on average than companion animal veterinarians.

While older generations reported higher well-being and greater job satisfaction than their small animal peers, younger veterinarians in their first decade of practice tend to report lower job satisfaction compared to older colleagues.

3. Declining rural populations: Fewer young people are staying in or returning to rural communities, which means fewer aspiring veterinarians with deep ties to livestock agriculture. The increasing urbanization of America has led to a cultural disconnect — fewer students grow up around large animals, making the field less appealing or even intimidating.

Gender bias remains a challenge in bovine veterinary practice, particularly for newly graduated women veterinarians. A 2021 study in The Bovine Practitioner highlights the difficulties female veterinarians face in rural communities, where they are sometimes made to feel unwelcome.

However, other factors also influence career decisions, including the availability of child care, quality schools, and job opportunities for spouses. Outdated practice models may also contribute to recruitment challenges and that making rural veterinary careers more appealing will require structural changes that better align with the needs of today’s professionals.

4. Limited veterinary school seats: Despite high demand, veterinary schools have limited space, and competition is fierce. The American Association of Veterinary Medical Colleges says that roughly 3,000 students are admitted to veterinary schools each fall, with about half of applicants being rejected.

While many veterinary school applicants majored in an agriculture-related field, such as animal science, wildlife science, biochemistry, or food science, there are also many applicants who have biology or even pharmacy or engineering majors. Despite the fact that enrollment is going up in many veterinary schools and the disproportionate number of ag majors, not all schools prioritize large-animal medicine, further reducing the number of new graduates entering the large-animal sector.

The impact on agriculture and food security

The consequences of this shortage go beyond just farmers having a hard time scheduling vet visits.

Without enough large animal vets, farmers are left to handle more medical procedures themselves, which could increase the risk of improper treatment. Disease outbreaks, such as avian flu or bovine respiratory disease, can also become harder to contain without enough trained professionals monitoring and diagnosing issues.

If animal health continues to decline, the food supply chain could certainly be at risk.

How can existing large-animal vets and support staff help?

Although the shortage is a national issue, those currently in the field can take action to grow their profession and ensure its survival. Mentorship and outreach through educational programs like FFA, 4-H, and other educational programs for young people can have a very inspirational impact. Large-animal vets can take students “under their wing” who show an interest in agriculture. Invite students to shadow in the field!

Mentorship can also provide ways where the practice can be more sustainable. Sharing on-call responsibilities, improving scheduling, or incorporating more veterinary technicians into fieldwork can make for better work-life balance and job flexibility. Telemedicine is also emerging as a valuable tool for rural veterinary medicine. By offering virtual consultations for minor issues, veterinarians can reduce travel time and free up more resources for urgent cases.

As far as vet school is concerned, several states and federal programs offer loan forgiveness and financial incentives for students who commit to working in underserved rural areas. Large-animal vets can spread awareness about these opportunities and push for additional funding at the legislative level.

Veterinarians can also work with industry groups, universities, and policymakers to push for reforms that make large animal medicine more financially viable. Whether it’s lobbying for more rural veterinary school slots or increased loan repayment programs, collective action can make a difference.

Here’s what’s currently being done

Currently, veterinary colleges are working to adapt strategies to attract students and, hopefully, retain large animal veterinarians after graduation. Texas Tech, for example, will graduate its first class of veterinary students in the spring of this year. The school was established with the purpose of graduating veterinarians trained to work in rural areas. Their program focuses on offering opportunities to students who already have “deep life experiences” in rural America.

Louisiana State University is also offering early admission programs to 10 LSU-Agriculture graduates who meet specific criteria to focus on rural and agricultural commitments.

Another example is North Carolina State University, which has launched a rural scholars program specifically offering 10 weeks of individualized mentorship for veterinary students in large and production animal medicine.

On the federal level, NIFA launched the Veterinary Medicine Loan Repayment Program in 2010, offering loan repayment in exchange for service in these areas. From 2010-2022, the program received 2,061 applications and awarded 795 veterinarians, primarily in the Midwest and West.

Despite increased federal funding, awards remain at $25,000 per year for three years, while veterinary student debt has risen significantly. Several states have also developed their own loan repayment programs to retain veterinarians in rural areas.

Other livestock-specific organizations like the American Association of Swine Veterinarians and the AABP offer mentorship, debt relief, and professional development programs to support veterinarians in food animal practice.

Dr. K. Fred Gingrich II, executive director of the AABP explains in an AVMA article on the subject, “It is up to every individual practice owner in a rural community to understand what the next generation wants versus trying to force what we want to be done onto the next generation, which is unsuccessful.”

Looking ahead

The large-animal vet shortage isn’t going to fix itself, but with the right strategies it can be addressed. It will take a combination of mentorship, education, policy changes, and innovation to ensure that livestock producers have access to the veterinary care they need.

The agricultural community depends on these professionals, and if we want to safeguard the future of food production, we must invest in the next generation of large-animal vets.

Michelle Miller, the Farm Babe, is a farmer, public speaker, and writer who has worked for years with row crops, beef cattle, and sheep. She believes education is key in bridging the gap between farmers and consumers.