It’s the last thing you want first thing in the morning — a house without water. If you’re a member of one of the 23 million U.S. households with a private well, you may or may not know the drill. The great news about having a private well instead of a public water source is of course the well comes with no monthly water bill. As a rule, it’s free at the source. The downside is that when something happens to the well, you as the landowner are responsible for getting it fixed — and that can cost a couple of thousand dollars even for a small home.

Regular inspections and maintenance are sure-fire ways to extend the lifespan of your pump and avoid costly repairs. In most cases, this kind of maintenance is cost-free. But do the 15 percent of U.S. households using a private well even know how to maintain it, or did it simply come with the property they purchased?

Your local extension educator can be a great, cost-free resource for questions about your well, from water testing to points of contact regarding repairs. Below, we outline the basics as a primer of sorts, to help you keep the water pumping.

The basics

According to the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, private drinking water wells can be categorized as: Dug or bored wells; driven wells; and drilled wells.

Dug or bored wells are essentially holes in the ground dug by either a shovel or perhaps a backhoe. Lined with stones, brick, or tile, they tend to have a larger diameter but only 10 to 30 feet in depth. They’re not cased continuously, can absorb a lot of surface water, and thus become contaminated more easily.

Driven wells are created by driving a pipe into the ground and draw water from aquifers near the surface. These wells are cased continuously and run between 30 and 50 feet in depth. Though they have better casing and depth than dug wells, they’re still susceptible to contamination.

Drilled wells are created by percussion or rotary drills. These wells can be hundreds or perhaps even a thousand feet deep and require the installation of casing. Given the depth and style of casing, they’re much less likely to become contaminated.

The basic components of a well include the casing, which is a tube-shaped structure used to protect the well opening from ground water, contaminants, and other materials. Depending on where you live and what kind of soil you have, the casings could be made from either carbon or stainless steel, or perhaps plastic.

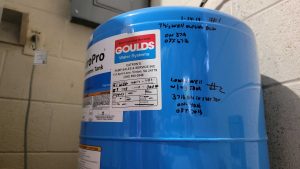

Wells for home use may utilize a jet pump, or submersible, depending on the depth. Jet pumps are mounted above the ground and draw water from wells in the 25-foot level. Deep private wells are more likely to use a submersible pump, which is placed inside the casing and connects to a power source on the surface. The pressure tank is the reservoir in which your water is stored from the well and supplied at an appropriate pressure to faucets and other fixtures. The pressure switch signals to the well’s pump when to start or stop running, depending on the pressure in the system.

Common problems for well-owners include failure of the pressure switch, pressure tank, and perhaps even the pump. Like all mechanical pieces, these units come with a warranty and do have a lifespan, which can vary greatly depending on the type of water one has and usage. As a rule, wells can operate perfectly for 20 years or more, but electrical shorts in any of these units can render them worthless if care isn’t taken.

The U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention offers a checklist of recommendations for well maintenance. It includes:

- Have a the well inspected and tested annually for mechanical problems or contamination. For a list of state-level water programs in your state, check the EPA homepage here.

- Well water should be tested more than once a year if there are recurrent gastrointestinal illnesses among the household members, or changes in odor or taste of the well water.

- Keep hazardous materials such as fertilizers and motor oil away from the well. This is particularly important if it’s a shallow well.

- Check the well cover and cap from time to time to make sure it’s intact.

From experience

Having grown up on a farm myself, the basic knowledge of well mechanics is something I just learned as a kid. As a landowner today, I’ve had to rely on that more than once.

In addition to your local extension educator, just know in advance the name of a local well driller and have it in the back of your mind in the case of a malfunction. Ask your neighbors who they’ve used in the past. If you live in a rural community, there probably aren’t that many well contractors, and the few who operate there do all the work and know the area well.

Wells are a specialty in their own right, and there’s no point calling a plumber if they malfunction. Most contractors who work with wells are also electricians, or at know enough about electrical workings to point you in the right direction.

Over the last 16 years, I’ve had to replace two pumps at different locations, a pressure switch, and a pressure tank. Keep in mind that one malfunction will lead to another. If there’s a problem with the pressure tank or switch, the pump may start and stop too frequently and burn the motor out. Also, if there’s a lot of iron in the water, casings and other mechanical parts in the unit can corrode.

The upside to having a well though is that it’s cheaper and much more convenient than paying a commercial vendor. Submersible pumps range in cost from $400 to $2,000, with jet pumps leveling off about $1,200. The average price of the pump plus labor though could be another thousand or so depending on how much work needs to be done.

With proper maintenance and awareness, you can avoid those costs and keep pumping clean water for years. One of the pumps I replaced was 30 years old, and I’m hoping the new one I bought lasts the same.

Brian Boyce is an award-winning writer living on a farm in west-central Indiana. You can see more of his work at the Boyce Group homepage.