A certain “PLU code” post had recently gone viral across social media, but the actual facts behind it aren’t as straightforward as what it claims — and some of it is downright wrong.

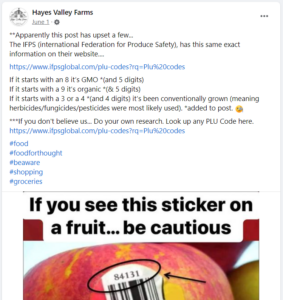

Here is one example of the post on Facebook:

The post claims that if a sticker on produce starts with the number “8,” the produce is genetically modified, but this isn’t true. There are only 13 commercially available GMO crops, and a majority of them are used toward the “junk food” processed food market. Although everything we eat is modified in some way, GMO more colloquially tends to refer to very specific plant breeding methods like transgenesis. Around 98 percent to 99 percent of fresh produce is non-GMO by default. The only GMO fresh produce crops are: pineapple, squash, corn, papaya, potato, and apple, but it’s an extremely small percentage of these crops to begin with.

The other claim on this viral false post is that if a sticker starts with a “9” (and has 5 digits) it means the produce is organic and if the sticker starts with a 3 or a 4 (and has 4 digits), the produce has been conventionally grown (and that herbicides/fungicides/pesticides were most likely used to grow the produce).

Here’s the true story: Herbicides and fungicides themselves are pesticides — they’re not a separate section of crop protection products. Organic produce can also be grown with many different types of pesticides. Sometimes, organics — particularly when it comes to insecticide use — are even grown with more pesticides than non-organics.

The link to more information in this viral post goes to the International Federation for Produce Standards (IFPS). The IFPS is not a regulatory agency and has no real control over produce labeling. The numbers on produce stickers are called PLUs (price look up codes). In the United States, there are no requirements for PLUs. The IFPS sets the standard system for PLUs in the U.S., but again, there are no federal regulations about produce labeling (just voluntary labeling under 21 CFR 101.45).

Not every grocery store follows the IFPS list of PLUs, and even the IFPS itself says, “The PLU system is voluntary and based on business needs. It is not regulated by a governmental agency.”

The IFPS PLUs do somewhat follow the claims made in this post. Four-digit codes that start with a “3” or “4” do identify conventionally grown produce. These codes function as the “standard” code for that particular type of produce. If a produce is organic, a 9 is simply added at the beginning of the existing four-digit code for that product. This makes the code five digits and means all organic produce starts with a “9.” Organic produce does not have a different code to conventionally grown produce, it just has a 9 added at the beginning.

If a produce item does not have a standard PLU, a retailer can make their own. This and the fact that following IFPS standards are voluntary, means that there is no guarantee that produce you find in a grocery store will always follow these rules.

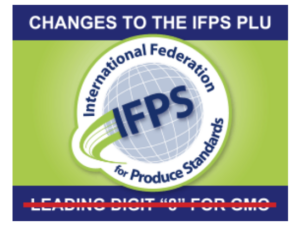

The IFPS has no other prefixes that mean anything, including a number to denote GMO produce. At one point, the prefix “8” (adding 8 to the beginning of an existing code) was being considered as a way to identify GMO produce, but it was never implemented. In the future, the prefix 8 will be used to identify the increasing varieties of produce items as new things enter the market. The prefix 8 was never used (and never will be used) to identify GMO produce.

In fact, this falsehood got so out of hand that the IFPS decided to address it on their homepage with a graphic and news release in the wake of this viral post.

The most important thing you can do if you have any concerns is to buy local or U.S.-grown produce to support what’s fresh and local. Farmers have a very small window to work with to move their fresh market crops and are under extremely difficult pressures regarding regulations, logistics, cost of production, labor challenges and more, so supporting local farmers has a big impact.

One last thing to mention about the viral post is that it claims that GMOs are bad, when they certainly are not. Scientists and plant breeders with Ph.D.s in the topic spend decades of their lives and hundreds of millions of dollars in research to produce plants that are better for farmers and the world. If GMOs were worse, farmers wouldn’t buy those seeds. If organic was better, everyone would be doing it.

Farming is complicated. It’s not black and white, and what works for one may not work for another. Regardless of how plants are bred, scientists select varieties based on disease resistance, size, shape, shelf life, color, size or flavor. A label or sticker doesn’t tell you much about that. Plants are bred and selected for a purpose. There are herbicide tolerant varieties of GMO plants (like GMO corn), non GMO plants (herbicide tolerant cilantro), and even organic plants like lettuce. Different types of plant breeding methods can produce desirable outcomes.

Labels are usually only there to sell you something and stickers aren’t helping you be more informed. Want to be more informed on what you’re buying? “Do your own research” by talking to people who actually do research about what they do and why. Talk to university extension agents, professors, food inspectors and scientists with doctorates who do this for a living, not mainstream media and fearmongering sales campaigns.

And remember that while some of this viral post may be right, the most important parts of it are wrong, and your produce is never guaranteed to follow these standards.

Michelle Miller, the Farm Babe, is a farmer, public speaker, and writer who has worked for years with row crops, beef cattle, and sheep. She believes education is key in bridging the gap between farmers and consumers.