Since most of the water that leaves cropland in the upper Midwest via tile drainage occurs during the months of November through April, this is an appropriate time to take a closer look at the relationship of tile drainage systems and soil health. While tile drainage doesn’t typically have a huge impact on soil health, soil health can have a major impact on how well a subsurface drainage system performs. Across the Midwestern U.S., a large percentage of cropland acres have tile drainage systems in place, but how well are they functioning?

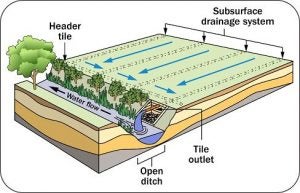

Tile drainage systems consist of ceramic, concrete, or perforated plastic tubes that are placed at depth in the soil to allow any water that would move out of the soil under the force of gravity to drain along the tile line to an outlet somewhere lower on the landscape, or to a site where the water might be pumped to get it to a place where it could enter a gravitational drainage way. By removing only excess water that would otherwise have kept the land un-croppable for all or part of the year, tile drainage has brought a great deal of land into production, while removing water from the landscape faster than it would have by streamflow or downward movement into a resident aquifer.

For a tile drainage system to function efficiently, water must not only be able to infiltrate the soil surface, but also permeate downward to the depth of the tile. We know that a tile system is functioning by observing the amount of water that runs out of the lower end of the line. As with many things in agriculture, timing can be very important to a profitable outcome. It is important for water to not sit on the surface of the soil from the time of planting a crop through harvest of that crop. It is during this time of year that farmers need to be in the field with equipment to plant, spray, harvest or perform other operations, and plants need a moist, but not saturated, soil to grow in. Enter the role of soil health and stable soil aggregates.

Soil aggregates are all the lumps, clumps and crumbs in the soil that are made up of sand, silt, clay and organic matter, stuck together by biologically produced sticky substances, herein referred to as glues. If the soil is functioning properly as a biological system, these glues will make and preserve aggregates that remain stable even when wet. These aggregates act like marbles in a jar, allowing spaces for water and air to move through the soil. If soil aggregates aren’t stable at the soil surface when the soil surface gets wet, they collapse resulting in fewer and smaller spaces for water to move downward into the soil.

I have witnessed this phenomenon many times where water has ponded on the surface of an unfrozen soil that has a tile drainage system in place. There are currently millions of acres of cropland with tile drainage systems where the water does not move downward from the soil surface at an acceptable rate. Often the water will evaporate from the soil surface at a greater rate than it moves down through the soil and out of the tile! In this way, dysfunctional unhealthy soil with unstable soil aggregates may result in a tile drainage system that does not provide the expected return on investment.

Because many of the soils in the upper Midwest with tile drainage systems originally had high levels of soil organic matter and were very productive, it is assumed that they continue to be healthy and functioning today. However, after a number of years of excessive tillage, lack of rotation diversity, and little cover on the soil, the majority of these soils have only a fraction of the soil biology that once inhabited them. This has correspondingly resulted in the degradation of the glues that keep soil aggregates stable and consequently reduced water infiltration into the soil.

The point of this whole discussion is that producers who have invested in tile drainage systems, but are not purposely managing for soil health, are most likely not realizing the most return on their drainage system investment. Improving soil function by reducing tillage, increasing plant diversity (i.e. crop and cover crop rotation), keeping living roots in the soil as much of the time as possible, and keeping the soil covered, will restore soil aggregate stability that will allow tile drainage systems to function as expected by removing water from the soil during critical times of the year. If your tile drainage system is not working as well as it could, I encourage you to examine your own soils and learn more about restoring soil health on your land.

References

- Tile vs. no tile and tilled vs. no tillage

- Controlled drainage and tillage systems

- Soil health assessment

Jon Stika is a retired Natural Resources Conservation Service soil health instructor and currently is the brewer at Phat Fish Brewing Company and assists with agricultural research at the North Dakota State University Dickinson Research Extension Center. He is also the author of “A Soil Owner’s Manual: How to Restore and Maintain Soil Health.”