Justin Smith Morrill, a young senator from Vermont, had a vision for all Americans to have access to higher education — which, in the early 1800s, had been reserved for elite, wealthy white males. Morrill developed a proposal in 1857 to grant land to each state for the establishment of public universities. Morrill was determined in his vision and spent years to achieve support for this well-intentioned proposal.

He introduced the land-grant concept in 1857, and received the congressional approval in 1859. That victory quickly faded when President James Buchanan vetoed Morrill’s legislative proposal. Morrill regrouped and resubmitted his proposal during the Civil War, where he included engineering and military sciences in the language — studies and skills critical to soldiers’ sustained livelihood. In 1862, Morrill’s Act was accepted and signed by President Abraham Lincoln — the same Lincoln who signed the Emancipation Proclamation in 1862 to end slavery.

I pause for the historical correlation between Morrill’s well-intentioned “state universities for all” and Lincoln’s legacy signature of the Emancipation Proclamation, because both pieces of transformational legislation were hindered, undermined, and null to millions of Blacks bound by the defiant, segregationist laws of the South. Because of their race, Blacks were denied admission to the land-grant universities created by the Morrill Act of 1862. Lincoln’s 1862 signature on the Emancipation Proclamation, intended to outlaw slavery on January 1, 1863. With the stroke of a pen, 3.5 million enslaved people of African descent were no longer required to be the property of others and perform pain-inducing free labor. Yet, there was also no infrastructure in place to adequately provide the 3.5 million new Americans capital to move from being human property to being land property owners, nor were there formal education opportunities to advance themselves and take care of their families.

They were free from chains but not truly to chart their own course as their white counterparts were now being given tools to do so.

It was 28 years after the 1862 land-grant system was established that Justin Morrill introduced a Second Morrill Act to address the race-restrictions. The Second Morrill Act of 1890 required the former Confederate states to establish sister universities for Blacks — creating the 1890 Historically Black Land-Grant Universities, which were some of the first Historically Black Colleges and Universities (HBCUs) in the nation. There are 19 historically Black land-grant institutions — public, agricultural, research, and extension vessels that educate the nation’s top Black agricultural scientists and economists, conservationists, veterinarians, researchers, and engineers.

Morrill is referred to as the Father of Land Grant Institutions, and his vision was just as necessary 150 years ago as it is today. A vision still not fully realized. The equality and access he forged with the Second Morrill Act of 1890 shifted the nation in a direction of education and opportunity for all. Yet, over the years, congressional accountability reports and studies reveal unequal distribution of state matching funds. While 1862 land grant universities annually receive full one-to-one matching dollars for federal grant funds, 60 percent of 1890 universities have not received full state matching commitment.

Oversight by Congress of the state’s land grant formula has been a repeated ask of 1890 Land Grant Administrators. Transcripts from a House Agriculture Committee hearing reflect the testimonies of inequitable funding — leaving 1890s in a scramble to request match waivers from the U.S. Department of Agriculture in order to receive their entitled research and extension allocations. The shortage of state dollars leaves universities to makeup deficits with general operating funds that are intended to be spent on academic programs — hindering the ability to attract new instructors and upgrade curriculum and research conditions to remain competitive and compliant in higher education.

Despite the inequalities, these agricultural land grant universities have been resilient — providing premier education to the agricultural industry’s most underrepresented population, leading inclusive innovation research to meet the needs of all communities and delivering outreach and education to serve the underserved and rural population. 1890 Land Grants are pooling their expertise and network through Centers of Excellence to increase sustainability of agricultural enterprises, address global food challenges, and expand the pipeline to recruit the next generation of agricultural leaders. These universities deliver programs that emphasize agricultural diversification, marketing strategies, and risk management to small and disadvantaged farmers.

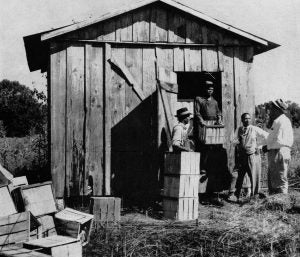

Thumb through the history books of these institutions and you will find the genius of Booker T. Washington, founder of the Tuskegee Normal and Industrial School (now Tuskegee University) and the peanut legacy of George Washington Carver, who brought school to the sharecroppers with his Jessup Wagon, defining extension — reaching Black farmers who couldn’t access education first-hand. In agricultural news, 1890s are applying teaching, researching, and extension to medicinal plants — Southern University is the first Historically Black Grant University to launch a medical marijuana program, and hemp discovery is prevalent at multiple 1890s, such as Delaware State, Tennessee State, and Central State University. Out of the halls of the buildings, some of which were built by students, are an alumni yearbook of agricultural academic excellence.

I am a proud graduate of an 1890 land-grant university, and I’ll be the first to endorse the premier academics, entrepreneurial insight, and community engagement these young people will bring to our industry — if given an opportunity. A 2015 Purdue University study on agricultural and natural resources careers projects the demand for these graduates to exceed supply by 39 percent. The agricultural industry has pledged to make their workplaces more inclusive and informed to address the broad needs of its customers — here is your talent pool!

These 1890 Land Grant Universities are the agricultural educators, talent developers, research innovators, and service providers critical to the survival of the INCLUSIVE human race:

- Alabama A&M University

- Alcorn State University

- Central State University

- Delaware State University

- Florida A&M University

- Fort Valley State University

- Kentucky State University

- Langston University

- Lincoln University

- North Carolina A&T State University

- Prairie View A&M University

- South Carolina State University

- Southern University System

- Tennessee State University

- Tuskegee University

- University of Arkansas Pine Bluff

- University of Maryland Eastern Shore

- Virginia State University

- West Virginia State University

Bea Wilson is a diversity strategist and agricultural professional passionate about the next generation of agricultural leaders. She owns IDEATION308, a diversity consulting firm in Upper Marlboro, Maryland. Twitter: @IDEATION308