Recently, I became obsessed with Bitcoin and blockchain. My obsession was triggered by an article in New Scientist, Should nations try to ban bitcoin because of its environmental impact? (China already has.)

An analysis by the University of Cambridge reveals that “bitcoin accounts for 0.69 per cent of all electricity consumption worldwide. It also requires vast amounts of water, both for electricity production and for data-center cooling.” And my thoughts ran something like this: In a world where electricity production is still largely dependent on fossil fuels, why do we need power and water hungry data centers to support people’s desire to invest in … blue sky and pyramid schemes? Because of the “mining” involved in verifying and securing a block of transactions, a single transaction requires about 1,400 kWh of power — enough to run the average household for four months — and over 4,000 gallons of water.

Now that you bitcoin investors are all yelling at me, let me explain.

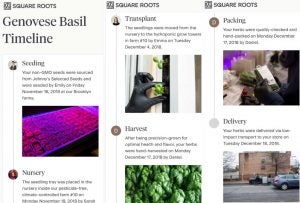

Blockchain, I confess, is a worthwhile invention. Say a lettuce farmer puts a digital tag containing his name, the variety of lettuce, the date it was harvested, and the field it came from, on a carton being shipped to a wholesaler. That’s a block of information. The wholesaler zaps the tag with his laser reader (think grocery line checkout here), uploads his handling and shipping information, (another block), and sends the carton to a distributor, who adds another block to the chain. The last block is added at the grocery checkout, and might include data about the purchaser, such as a phone number.

Then suppose the lettuce is contaminated with E. coli, and the customer gets sick, along with a bunch of other customers. An investigation of the source of the E. coli begins. Looking at the blockchain, an inspector can determine the source of the lettuce in about 2.2 seconds. With the old method of using a paper trail at every point of change in ownership, the inspector may require several weeks to trace the source of infection. Meanwhile, thousands of pounds of lettuce are thrown away by customers or stores, and all growers are suspect until proven innocent.

So blockchains in commerce improves safety, productivity, and trust. Each block has an identifying number, called a hash, that goes with the block wherever it goes. When a new block is added, the hash from the previous block is included with the hash from the new block, creating the “chain.” Hashes are encrypted so a handler cannot unlock the previous block and change its contents. In this world where counterfeit pills and trademark theft is a growing problem, a blockchain that begins with the manufacturer and ends at retail gives assurance the product you are buying is genuine.

Bulk commodities can also be blockchained, beginning with the farmer’s delivery to an elevator. The co-mingled information on a bin can be put in a block and passed on to a buyer, who can then co-mingle grain from several vendors to make a shipload, put it in a block and send it on to a buyer. If the buyer of the shipload finds a problem, it can be quickly traced back through the chain, perhaps to an individual farmer. Presently, this sort of thing is done with mountains of paper work at each change of ownership.

Now back to bitcoin and its knockoffs. There are some 18,000 digital coin programs worldwide using blockchains to secure transactions. Not all of them are as power hungry as bitcoin, but taken together these data centers’ use of electricity and cooling water is tremendous. Are they really needed? Some people argue that digital money that bypasses banks, mortgage lenders and money managers, etc. is the future of commerce. But currencies must be backed by faith in something. The U.S. dollar used to be backed by gold stored in Fort Knox, and still is to some extent, as people and countries can exchange their dollars for gold. Mostly the dollar is backed by faith in the U.S. government to pay its bills, and that is backed by the taxing authority of the government.

Does anything back the digital currencies? Well of course: It’s the dollar, or the currency of any other country. And if there is a run on a digital currency, such as bitcoin, to exchange an investor’s tokens for dollars, the value of a token will fall and thousands of people will lose most of their investment. The value of a dollar may slowly erode via inflation, but changes in value won’t be large as long as the Federal Reserve does its job. And bank deposits are insured up to $250,000.

The dollar can already be exchanged digitally. I can go the bank, fill out some paperwork, and send dollars in my account to some account far away. Walmart deducts your check from your bank account by sending it digitally to your bank. Credit cards exchange dollars digitally. But it gripes me every time I use one that 3 percent or more is going, digitally, to some bank’s bottom line.

Jack DeWitt is a farmer-agronomist with farming experience that spans the decades since the end of horse farming to the age of GPS and precision farming. He recounts all and predicts how we can have a future world with abundant food in his book “World Food Unlimited.” A version of this article was republished from Agri-Times Northwest with permission.