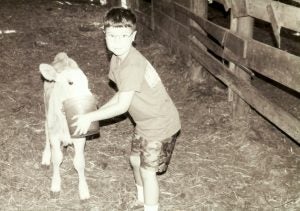

Mama and Daddy gave me a calf when I was 5 years old. She was small, sweet, and terribly clumsy; but that’s normal for a young calf, my parents told me. She would grow out of her awkwardness and become a good cow — even a great one. She was soft to the touch, curious and calm. Her coat was light brown. I named her Muffin.

From the start, I adored Muffin, and I jumped at the chance to see her. So whenever Mama or Daddy went to the barn, I followed and carried a rusty coffee can filled with feed on many of these trips. Standing in the north shed, I’d scoop grain out of the can with my little hands and walk softly toward Muffin. Cautious, she’d sniff the air above my palms as if she didn’t trust me at first and then slowly start to eat. When the feed was gone, she licked the fingers of one hand clean while I rubbed her head with the other. She tolerated my childish affection and at times seemed to return it.

Muffin grew quickly from a calf into a yearling. A couple years later, she gave birth in a back field to a calf of her own. She doted on her first-born and all her other offspring, consistently raising healthy, hearty calves.

At times, she even adopted others, like when another cow had twins and rejected one of her babies. Rather than letting that calf go hungry — or having my family and I feed it formula from a bottle — Muffin raised it. As my parents had promised, she became one of the best cows in our herd.

All the while, Muffin kept her gentle demeanor. Throughout my childhood and teenage years — and even into adulthood — I could walk right up to her in an open pasture. I could rub her head, scratch her neck, pat her front shoulder. Some cows scampered away when I approached, but Muffin allowed the attention.

In her later years, I often carried a small bucket of grain with me to the field. Before I set the pail down for her to eat, I’d grab a handful of pellets and reach out to her, just like old times.

Two years ago, I found Muffin lying in the mud just south of our barn. Apparently, she had come into heat, and our bull mounted her. Beneath his one-ton frame, Muffin lost her footing, gave way, and crumpled to the ground. Pushing her from the side and encouraging her with hopeful words, I tried to help her stand, but my efforts were useless. Her rear legs wouldn’t work. I feared her back was broken. Little can be done for a cow in this condition.

With the tractor, front-end loader, and heavy-duty straps, Daddy and I lifted Muffin’s back half and moved her to the small lot just west of the barn. We set her under a shade tree and arranged her limp legs in a comfortable position. Trying our best to resist despair, we brought her water and more grain and hay than she could eat.

For three days, Muffin rested. When it became clear that she wouldn’t — couldn’t — stand, I called the local vet. He drove to our farm, examined Muffin, and gave his verdict. She’d never walk again. At my request, he gave her a heavy anesthetic. The lethal dose cost me $120, but I couldn’t bring myself to shoot her.

As Muffin died, I crouched beside her, patting her neck and rubbing the bony nub between her ears. She was silent, stoic as her head sank. Not knowing what to do, I whispered, Thank you. Muffin’s eyes closed and her body shuddered, scaring the flies and me.

I loved Muffin. Today, her picture sits on my bedroom bookshelf, right next to my collection of Wendell Berry books. But she was decidedly not a pet. She was a cow, livestock, and I was — am, even if now only in spirit — a farmer. I sold the calves that she raised at a local auction. I used that money to buy my first vehicle, to purchase other cows, to get through college. Yet I didn’t treat Muffin as a machine, a walking factory whose value depended solely on a profit margin. I’ve seen that version of farming. It is heartbreaking: for the land, the animals, and even the farmers.

Unlike many cows in modern America, Muffin spent her whole life — all 20 years of it, a bovine eternity — on the same plot of land. She had a name and not just a number. That’s worth something.

Farming is at its best when it values both affection and production. When it balances the need for profits with the richness of relationships. When it considers empathy alongside efficiency. If the virtues of affection and care are forgotten, ignored, or abandoned, agriculture can turn cold and callous. On many levels, it can become destructive.

In life and death, Muffin taught me the power and purpose of connection. She helped me understand value in a richer sense. She showed me what agriculture can be.

For that — for her — I am grateful.

Brooks Lamb is from the small, rural community of Holt’s Corner, Tennessee, and currently lives in Louisville, Kentucky. He recently completed his graduate studies at Yale School of the Environment and now works as the Program Associate & Special Assistant to the President at American Farmland Trust.