What does racism have to do with food? Several people asked me this question last week after I decided to take the #amplifymelanatedvoices challenge that was created by Jessica Wilson (@jessicawilson.msrd) and Alishia McCullough (@blackandembodied) on Instagram. Their challenge was from June 1 to 7 and set out to 1) mute white accounts doing social justice work 2) follow Black, Indigenous, and People of Color (BIPOC) speaking directly from their lived experience, and 3) Share content created by BIPOC in our stories and tag their work.

I learned so much during this time, but my participation in this challenge is what sparked those messages. Some of my followers, it seems, didn’t see the connection between racism and food.

View this post on Instagram

So, what does #BlackLivesMatter and racism have to do with the U.S. food system? A lot. Our agricultural landscape here has been shaped by our nation’s history of slavery and structural racism. The massive agricultural system in the South was built on the backs of enslaved people from Africa and their children. Native Americans were often violently removed from their homelands, which was then further partitioned by federal laws. Freed slaves and their descendants accumulated 19 million acres of land in the decades after the Civil War. In 1910, 14 percent of all farm owner-operators were Black or African Americans, but by 2012, they comprised only 1.5 percent.

The cause of that decline is entrenched in structural racism. A series of federal Homestead Acts gave mainly white male settlers and corporations extremely subsidized land. About 93 million people alive today are descendants of those who received land through the Homestead Acts, which likely includes a number of today’s white farmers and landowners.

The California Alien Land Law of 1913, prohibited many different people of color from owning land. They were also denied reparations after the abolition of slavery, as well as labor protections like minimum wage, union rights, and social security when they worked on farms. The government gave unequal funding to historically Black land-grant universities, and the USDA discriminated against Black, Native American, Latinx, and women farmers in its lending and other forms of support for decades.

In 1997, Timothy Pigford alongside 400 African American farmers filed a class action lawsuit against the USDA, which alleged that from 1981 to 1997, USDA officials ignored complaints brought to them by Black farmers and that they were denied loans and other support because of rampant discrimination. In 1999 the government settled the case for $1 billion, and more than 16,000 Black farmers received $50,000 each.

However, institutional racism continues to permeate the U.S. farming industry. Heirs property is a legal term for land that is owned by two or more people, usually people with a common ancestor who has died without leaving a will. It is the leading cause of Black involuntary land loss. These landowners don’t qualify for certain USDA loans to purchase livestock or cover the cost of planting. Individual heirs can’t use their land as collateral with banks and other institutions, and so are denied private financing and federal home-improvement loans, and they typically aren’t eligible for disaster relief.

Fourteen states have passed the Uniform Partition of Heirs Property Act, which expands heirs’ rights in partition actions and can help heirs’ property owners gain access to USDA programs. It has not been passed in North Carolina, Mississippi, Florida, Louisiana, and Tennessee. The 2018 Farm Bill created a lending program that, if funded by Congress, would support local organizations providing legal assistance to heirs’ property owners.

White Americans are most likely to own land and benefit from the wealth it generates. A recent study shows that:

“From 2012 to 2014, white people comprised over 97 percent of non-farming landowners, 96 percent of owner-operators, and 86 percent of tenant operators. They also generated 98 percent of all farm-related income from land ownership and 97 percent of the income that comes from operating farms.

“On the other hand, farmers of color (Black, Asian, Native American, Pacific Islander, and those reporting more than one race) comprised less than 3 percent of non-farming landowners and less than 4 percent of owner-operators. They were more likely to be tenants than owners; they also owned less land and smaller farms, and generated less wealth from farming than their white counterparts.

“Meanwhile, Latinx farmers comprised about 2 percent of non-farming landowners and about 6 percent of owner-operators and tenant operators, well below their 17 percent representation in the U.S. population. They also comprised over 80 percent of farm laborers, a notoriously under-compensated, difficult, and vulnerable position in U.S. farming. This data provides evidence of ongoing racial, ethnic and gender disparities in agriculture in the United States.”

Racial and ethnic disparities exist between people of color and whites when it comes to food insecurity as well.

Another recent study shows:

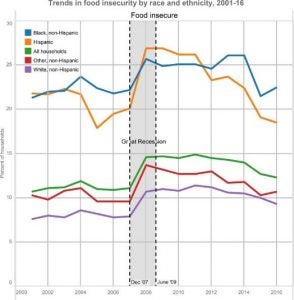

“For over 20 years, food insecurity has been assessed and monitored by the USDA at the federal level. Although levels of food insecurity have declined and risen over this period, one trend that has continued to persist is the gap in the prevalence of food insecurity between people of color and whites. An analysis examining trends in food insecurity from 2001 to 2016 found that food insecurity rates for both non-Hispanic black and Hispanic households were at least twice that of non-Hispanic white households (See Figure 1). Moreover, while race/ethnic specific rates from the USDA are not available for all subgroups, other studies assessing food insecurity among American Indian/Alaska Native (AI/AN) report similar results. Using the Current Population Survey-Food Security Supplement, Jernigan et al., 2017 found that from 2000 to 2010, 25% of AI/ANs remained consistently food insecure and AI/ANs were twice as likely to be food insecure compared to whites.”

Figure 1

Although the relationship between race/ethnicity and food insecurity is complex and connected with other established determinants of food insecurity including poverty, unemployment, incarceration, and disability, there is growing recognition in the health sciences, particularly public health, that discrimination and structural racism are key contributors to inequity in health behaviors and outcomes.

So, what can we do to help?

- First, you can educate yourself about racism in food and agriculture by reading articles here, here and here, listening to the podcast 1619, reading books such as Freedom Farmers, and Dispossession. In addition, there are 279 sources in this Annotated Bibliography on Structural Racism Present in the U.S. Food System.

- Second, you can donate to organizations working to strengthen food justice, land access, and food access in the Black community.

- Third, you can buy food from Black farmers and Black-owned food businesses.

- Lastly, you can vote for lawmakers who are committed to food justice and advocate for policies that keep Black farmers on their land as well as policies that promote equity in food access and health by addressing the legacy of racial, ethnic, and class inequality. After all, food justice is racial justice.

Food Science Babe is the pseudonym of an agvocate and writer who focuses specifically on the science behind our food. She has a degree in chemical engineering and has worked in the food industry for more than decade, both in the conventional and in the natural/organic sectors.