I write about GMOs on a somewhat regular basis, but sometimes it’s a topic worth revisiting on a very basic explanation.

In short, “GMO” stands for genetically modified organism. The interesting thing about this is that everything we eat has been genetically modified in some way. But, it’s also clear that in the public discourse, the term “GMO” has been co-opted outside of scientific circles to broadly and vaguely refer to foods and other products that have been engineered in certain lab settings, no matter how natural the end result is.

“Every technique that scientists use in the lab to move DNA within or between organisms, and the enzymes we use to do that, are things that we have discovered in nature and figured out how they work,” said Val Giddings, with the Information Technology & Innovation Foundation.

Still, just the fact that there is no accepted definition of “GMO” has made discussions between farmers, scientists, media, and the public difficult, at times, as perceived definitions, labeling, and scientific terminology don’t line up.

Back in the 1980s, Syngenta scientist Mary-Dell Chilton was one of the first people to develop one of these modern types of GMOs, and she explains the process here in a video interview:

Chilton is often referred to as the “Mother of Genetic Modification,” and she has explained how switching genes between species is somewhat of a pretty natural process. Since humans have been modifying plants for thousands of years, there have been numerous ways of changing crop genes for desired outcomes, however “GMO” technically would end up relating to cisgenic or transgenic breeding.

Transgenic refers to transferring genes from one species to another. For example, transferring a naturally occurring agrobacterium like Bacillus thuringiensis (also known as Bt) into the corn plant so it harms certain insects like the corn borer or root worm, but nothing else.

On our farm, we grow GMO corn and use these traits. Years ago, we used to have to spray insecticide, but now, thanks to the Bt trait, we no longer have to spray these chemicals. It’s a win-win for farmers, the environment, beneficial insects, and the end consumer. Other GMO crops exist to allow farmers to kill weeds without killing the crop itself (herbicide tolerance) while eliminating horrible hand weeding across millions of acres with labor shortages; they may offer farmers access to safer herbicides (weed killer); or maybe they exist to save farmer’s crops from devastating disease and drought, while reducing food waste. There are a number of ways modern GMO crops can be used or bred.

Changing plants for desired traits is nothing new. Herbicide-tolerant crops are also part of “Non GMO” plants, while organic and non-GMO plant breeding methods can also be bred in a laboratory, patented, be pest- or disease-resistant.

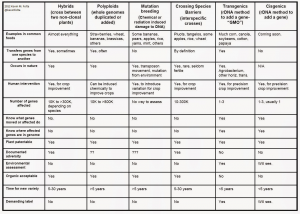

The whole process is quite interesting … I’d be really curious to see who came up with the term “GMO,” because it sounds like some sort of weird creepy mutation we shouldn’t put in our bodies. Yet the word “organic” may drum up some pretty “feel good” feelings of purity, when in reality, the plant breeding methods are not really the case. Here is a chart that further explains:

So as you can see, “GMO” is moreso a marketing buzzword for food labeling to sell products. Ask any scientist or plant geneticist … the ones I’ve spoken to at plant breeding and farming conferences and university laboratories explain that when they want to solve a problem in agriculture, the WAY that they get to the desired outcome doesn’t matter so much as the solution does. Some plant breeding methods are much more random, yet don’t require nearly as much testing. The answer to the problem facing the farmer can be found throughout several different methods of plant breeding regardless of marketing label.

Remember this the next time you’re looking at food labels. If, say for example, the Non-GMO Project wants to sell a product based on a breeding method, are they really being transparent as we are led to believe? Would they put you in touch with the farmers and scientists to further explain the methodology? Perhaps not … and perhaps their goal is to make certain labels sound scary or pure to drum up more sales for the $19 billion food marketing label. If you have any more questions about plant breeding, there are many more resources that prove GMOs are no more dangerous or scary than anything else we’ve done to plants for thousands of years and are proven safe by pretty much every food regulatory agency in the world.

Michelle Miller, the Farm Babe, is an Iowa-based farmer, public speaker, and writer, who lives and works with her boyfriend on their farm, which consists of row crops, beef cattle, and sheep. She believes education is key in bridging the gap between farmers and consumers.