It can be helpful to recognize patterns of false arguments when spotting misinformation. If you’re able to spot these logical fallacies, you don’t even necessarily need to know all of the facts about a given ingredient to know that you should question the information that follows.

Here are four examples of common false arguments that are presented to scare consumers over specific foods or ingredients. Once you familiarize yourself with these common false arguments, you can become better equipped to identify food misinformation.

False Argument #1: This food ingredient is used as an ingredient in industrial cleaner/paint thinner/silly putty/antifreeze, therefore is not safe in food.

The most common example I’ve seen using this false argument is for trisodium phosphate, or TSP. The argument is that since this is used as an industrial cleaner, it can’t be safe in food.

However, there are many food ingredients that are used in various industrial applications that can also safely be used in food — and this is because dose matters. Of course, a large swig of concentrated, industrial grade TSP heavy duty cleaner is not safe to consume, but that doesn’t mean that a much smaller dose of food grade TSP at a much lower concentration in food isn’t safe.

Similarly, ingredients such as sodium bicarbonate (baking soda) and acetic acid (vinegar) are also used in heavy duty cleaning, but are used safely in many different foods as well. Just as baking soda is used as a leavening agent, TSP can be used for the same function — to create air bubbles in dough by reacting with acidic compounds, causing the dough to rise. Both baking soda and TSP can also serve as buffering agents, which resist changes in pH caused by the addition of more acidic ingredients during the production of a food item. This can help to maintain texture and increase the shelf-life of a food product.

False Argument #2: There are studies showing that a food ingredient causes cancer in rodents at extremely high doses, therefore it’s unsafe for humans to consume at any dose.

I wrote previously about aspartame and how it was classified in July 2023 by the International Agency for Research on Cancer as a Group 2B carcinogen. Group 2B substances are defined as “possibly carcinogenic to humans,” where there is limited or no evidence in humans as well as limited to insufficient evidence in animals. Although the IARC has concluded that aspartame is “possibly carcinogenic to humans,” the evidence for this is limited in humans, and it does not take into account the dose that a person can safely consume.

The World Health Organization and Food and Agriculture Organization’s Joint Expert Committee on Food Additives (JECFA) concluded that there was no sufficient reason to change the previously established daily intake of aspartame of 0-40 mg/kg body weight.

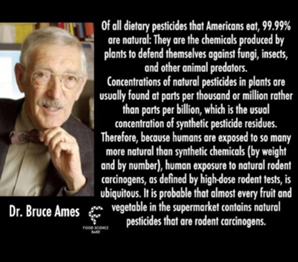

Ironically, Bruce N. Ames, Ph.D., developer of the Ames Test, a widely used test for potential carcinogens, calculated that “it is probable that almost every fruit and vegetable in the supermarket contains natural plant pesticides that are rodent carcinogens.” Of course, that doesn’t mean fruits and vegetables increase risk of cancer in humans even though that argument is used for food additives like aspartame.

False Argument #3: This food ingredient is unsafe due to studies showing negative health effects of a similar (but not the same) substance.

Two common arguments that come to mind here are regarding carrageenan as well as high fructose corn syrup (HFCS). The studies referenced to show negative effects of carrageenan aren’t even using food grade carrageenan at all.

This review explains:

“Carrageenan has been proven safe for human consumption; however, there has been significant confusion in the literature between CGN and the products of intentional acid-hydrolysis of CGN, which are degraded CGN (d-CGN) and poligeenan (PGN). In part, this confusion was due to the nomenclature used in early studies on CGN, where poligeenan was referred to as ‘degraded carrageenan’ (d-CGN) and ‘degraded carrageenan’ was simply referred to as carrageenan.

“Although this nomenclature has been corrected, confusion still exists resulting in misinterpretation of data and the subsequent dissemination of incorrect information regarding the safe dietary use of CGN.”

Several human and animal studies have contradicted claims that carrageenan is carcinogenic and demonstrated its safety. These studies found no link between carrageenan consumption and various health conditions, including cancer and digestive and reproductive disorders. Despite this, carrageenan continues to be confused with poligeenan.

A similar false argument happens quite frequently with HFCS, which often gets confused with pure fructose. The claim that fructose is “toxic” is based on rodent studies that examine acute effects of incredibly high doses of pure fructose. Obviously this isn’t evidence of HFCS or even fructose being “toxic” or harmful to humans when consumed in realistic amounts because 1) we aren’t mice, 2) the doses used were many times more than humans would consume from foods, 3) HFCS is not pure fructose, 4) we typically consume these sweeteners in conjunction with other ingredients, and 5) HFCS contains similar or even lower amounts of fructose as regular sugar, honey, or the other forms of sugar listed above, so one would not expect HFCS to be any worse as compared to other types of sugar.

In fact, the studies comparing intake of sucrose, HFCS, and other similar sweeteners such as honey have found they exert similar metabolic effects. I wrote more about both of these ingredients here.

False Argument #4: This ingredient is unsafe because it is one molecule away from (insert scary inedible chemical compound here).

This one is perhaps my favorite because it is so nonsensical. Although I’ve heard many arguments of this format, the one that always sticks out is that “margarine is one molecule away from plastic.” First, one molecule or even one atom difference in chemical structure can make something a vastly different substance with vastly different chemical properties.

Take water (H2O), for example. Imagine arguing that water is unsafe to consume because it’s only one atom away from hydrogen peroxide (H2O2). The same goes for the margarine and plastic argument, except that argument is even more ridiculous since it isn’t even accurate to begin with. Margarine is an emulsion of vegetable oils and water, while plastics are polymers made up of repeating units of ethylene, for example. I’m not even sure how this argument came about since they aren’t even one molecule different to begin with. Even if margarine were one molecule away from plastic, which it isn’t, that still wouldn’t mean that margarine is the same as plastic because one molecule or even one atom can make a huge difference in a chemical’s properties.

These are just a few of many logical fallacies that are presented to scare consumers about specific foods or ingredients. Unfortunately, it’s a very effective marketing tactic when trying to get consumers to buy a product that is being positioned as “safer” or “healthier,” and is often more expensive as well. So the next time someone tries to scare you about a safe ingredient that can also be used as an effective cleaner, make sure to point out the hypocrisy of the miracle apple cider vinegar superfood product they’re promoting too.

Food Science Babe is the pseudonym of an agvocate and writer who focuses specifically on the science behind our food. She has a degree in chemical engineering and has worked in the food industry for more than decade, both in the conventional and in the natural/organic sectors.