You probably read the title of this article and asked yourself one of these questions:

- “Do ruminants really have four stomachs?”

- “Who thinks ruminants have four stomachs?”

- “What’s a ruminant?”

- “Why is this even a topic of conversation?”

There seems to be a too-common misunderstanding that ruminants have four stomachs. I can’t begin to tell you the number of times that I’ve heard it said.

I’m not able to put my finger on the exact reason for the misunderstanding, because I think there may be multiple reasons why people are under the impression that ruminants have four stomachs. And, if I’m being honest, learning and genuinely understanding the complexities pertaining to the anatomy and physiology of ruminant digestion is no small feat. If you’ve ever taken a ruminant nutrition class, you’ll probably agree. It’s amazingly complex (yet extraordinarily interesting) when you get down to the science of it, but don’t worry; I’m not writing this to bore you with scientific jargon or to jump down “rabbit holes” involving the explanation of intricate digestive processes. I’m writing this to inform you that ruminants do not, in fact, have four stomachs. In layman’s terms, I’ll explain to you why, because it’s extremely important to understand (especially if you’re a producer or someone with an interest in raising these types of animals) when it comes to knowing how to take care of and properly feed ruminants.

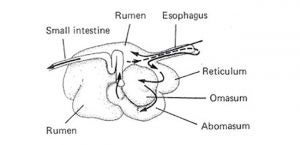

Ruminants are cloven-hoofed (meaning, hooves are “divided” or “split” into two toes) animals (including cattle, sheep, goats, etc.) that were uniquely designed to better utilize energy from the feedstuffs that they consume when compared to other herbivores. They’re different from monogastric animals (animals with one single-chambered stomach), as ruminants have one stomach composed of four distinct chambers (not four stomachs), each with specialized functions. The four chambers, in sequential order, are termed the rumen, reticulum, omasum, and abomasum.

Simply put, a ruminant’s digestive system was specially designed, anatomically and physiologically, to be that of a fermentation vat; it ferments feedstuffs and forages for the animal to use as sources of energy.

After being consumed by the animal, forage and/or feed is mixed with saliva to form a bolus, which travels from the mouth of the animal to the rumen via the esophagus. The rumen is the largest chamber of the stomach and the first compartment that comes into contact with the bolus. It is especially unique in the fact that its inner surface is covered with many small and distinct projections called “papillae” that function to increase the surface area of the rumen itself in order to allow for improved absorption of nutrients digested in the rumen. Moreover, it is in the rumen that the material ingested by the animal is mechanically processed and exposed to billions of bacteria, microbes, and protozoa that have the ability to break down cellulose and hemicellulose (which are components of plant cell walls) in a process we refer to as “foregut fermentation.”

Material is then passed from the rumen to the reticulum, which is the chamber attached to the rumen that has a characteristic honeycomb-patterned wall structure also covered in papillae. The rumen is the chamber of the stomach involved in the trapping of large feed particles in order to prevent them from being transported any further in the digestive system without being digested properly. The fact that the reticulum traps these large particles is what allows the animal to regurgitate, re-chew, and re-swallow the particulate matter, which is where we get the term “chewing the cud.”

Further processed material then enters the next chamber of the stomach, known as the omasum, which serves as the site of additional mechanical processing of forage and/or feedstuffs that the animal ingested. The walls of the omasum are made up of large, extending folds known as “laminae” that are attached very much like the way pages are bound in a book. Furthermore, the omasum rids or “squeezes out” some of the water from the material the animal has consumed in order to ensure that the water stays within the rumen environment as a means of maintaining proper rumen function. After all, the rumen is approximately 80 percent water.

Finally, material is then passed to the abomasum, or what we like to call the “true stomach,” which connects the omasum to the small intestine. It’s similar to the human stomach, since it’s the site of acid digestion instead of microbial fermentation. The abomasum is where stomach acid and digestive enzymes break down microbial protein, in addition to protein that was unable to be digested, in order to release nutrients to the animal for subsequent absorption by the small intestine.

Callie Burnett is a farm girl, animal scientist, and biologist whose heritage is deeply rooted in agriculture. She is an alumna of Clemson University with a Master of Science in Animal & Veterinary Sciences.