As ice and snow melt into American fields on a cold February day, farmers and their neighbors wonder when relief might spring forth. But in the year 2022 — now two years after the pandemic virus COVID-19 began freezing the world’s markets — it’s more than just warmer weather that will spell relief.

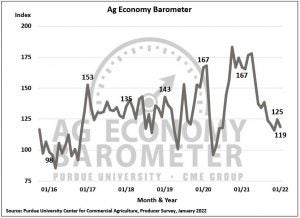

According to the Purdue University-CME Group Ag Economy Barometer report issued February 1, producers across the nation remain concerned about rising costs and supply chain disruptions. A sentiment index calculated monthly using 400 U.S. agricultural producers surveyed by telephone, the Ag Economy Barometer in February fell six points to 119. This represents the second-lowest reading since July 2020 when it stood at 118, as opposed to 153 the July prior and January 2017 before that.

Meanwhile, rural communities across the country are also manifesting the “blahs” when it comes to polling on everything from politics to social issues. And, all fingers point back to COVID-19. Two years later, the effects of the pandemic still linger. But amid the dismay are indeed shining rays of genuine progress, not just in improved health care networks, but the growing opportunity for remote work and professional opportunities. While inflation and labor shortages frustrate producers and manufacturers, it’s a terrific time to sell a house and find a job.

Tabby Flinn, Agriculture and Natural Resources Extension Educator for Purdue Extension in Vigo County, Indiana, agreed that much has changed over the last two years. Some changes have been problematic, and yet, some have been for the better. Meanwhile, their ag community has been actively engaged in supporting both the producers and the rural communities in which they serve the entire time.

Purdue University, in partnership with the Indiana State Department of Agriculture and the Indiana Rural Health Association, is sponsoring an innovative series titled Healthy Minds, Healthy Lives Mental Health Workshops. Designed to raise awareness of, and reduce the stigma associated with, mental health in the agriculture industry, the 23 free, one-day workshops facilitated by subject matter experts began February 10 and will run through July.

Flinn also noted that Purdue University’s Extension Service has been offering a dynamic podcast series Tools for Today’s Farmer: Navigating Uncertain Times, with features like Beating the Winter Blues and Overcoming Adversity — Don’t Ever Give Up.

Both programs are part of a concerted effort to metaphorically Judo-roll the opponent that has been COVID-19 into a positive direction.

Impact in the Heartland

The voters of Vigo County have the distinction of correctly picking the U.S. president in every election between 1956 and 2020, when the streak came to an end as the county went for the incumbent Republican President Donald Trump instead of the Democrat challenger, now-President Joe Biden. With a population of approximately 107,000, the county is served by Terre Haute as its seat, and it is home to Indiana State University, Rose-Hulman Institute of Technology, Saint Mary-of-the-Woods College, and the Ivy Tech Community College. Situated on Indiana’s western border with Illinois along the Interstate 70 corridor, about 168 miles northeast of St. Louis and 75 miles southwest of Indianapolis, it’s the middle of rural America surrounded by farmers and their land. All in all, a solid representative sampling of rural America and the farmers that make it what it is.

When asked how the pandemic changed agricultural production, and which of those changes were temporary and which altered the field perhaps permanently, Flinn said the regulations played a big factor.

Producers well remember how, in March of 2019, they were preparing to hit the fields for planting. And then came discussions of the quarantine. Before the soybeans were all planted, the United States was on a lock-down. Suddenly bank lobbies and supply stores were closed, farm kids and city kids alike were taking classes over Zoom, and masks were required nearly everywhere. This did create a big problem in terms of sourcing supplies as many employees simply stayed home.

Meanwhile, farmers have always worked remote from the farm, and so production went on nonetheless.

“Every year there is always a shortage of truck drivers,” Flinn said, noting it was significantly worse during this period. That demand for truck drivers continues today as the labor shortage mounts. Flinn said some producers were paying as much as $1,000 for a short haul of grain. With the supply chain snarled, parts and trucks themselves were in short supply — and to a large extent, that continues.

On the upside, farmers got introduced to new products and providers to replace those unavailable. And that can be a great thing, she said. Vendors and farmers alike had to figure out ways to get the job done and that will carry forward.

And while everyone in the world had to deal with the pandemic, all dealt with it differently. The issue was certainly felt differently in the cities as opposed to the suburbs and the rural areas, Flinn agreed.

“It definitely had a different impact for our rural communities as opposed to our suburban or urban,” she said, observing that Vigo County offers a dynamic blend with Terre Haute as a regional hub-city surrounded by more rural and suburban communities.

Due to the significantly lower population density, the virus didn’t spread as quickly as in major metropolitan centers. With about 265 people per square in Vigo County per the U.S. Census, next-door neighbor Clay County has 75 per square mile, and there are only 39 per square mile in Parke County. Lots of room and open air compared to the 3,200 people per square mile in Chicago’s Cook County, or 29,303 per square mile in New York City.

Granted, farmers typically spend a lot of time on their own operations, but even in the towns, there’s simply fewer people coagulated together. This did make enforcement of mask-wearing a bit of a struggle in some cases, but overall the virus spread was slower due to less contact. Yet one of the challenges to living in rural areas though is fewer options for health care. In that sense, Flinn said many communities such as Vigo County have made tremendous leaps with rural health initiatives. With two hospitals in Vigo County and a number of partner clinics throughout the area, access was, and remains, better than in years past.

“Our rural communities have come back a little faster than our suburban or urban communities because of the lower population density,” she said.

Because of the sudden shock dropped on the country by way of the pandemic, these health care partners and businesses have made significant strides in partnerships that will continue long after the virus is under control.

“I think it’s definitely changed the landscape, not necessarily for the worse, but perhaps for the better,” she said, noting the Spanish Flu in 1918 also provided a global learning experience for mass pandemics.

Another big change that will most likely become commonplace moving forward is remote work from home. With nearly a year of school and work done from the home, many technologies and purchases will remain in place as people accept that as the new normal.

Anyone involved in agriculture knows the 2021 crop season posed a riddle for producers, with terrific prices matched by record costs, and the added shortage of supplies and machinery only fueled the problem. COVID-related supply chain challenges and worker shortages mixed in with weather-related demand spikes to produce a truly unique season.

“It was a little bit of both,” Flinn said. Grain elevators had trouble getting trains in to haul grain out, and truckers themselves were scarce to be found. “It was nearly impossible to find people to drive cross-country.”

The price spikes and associated inflation set into place by this phenomenon will most likely run through 2023, Flinn said. Experts predict that over the next two years, the agriculture sector will continue to struggle with labor shortages, supplies, and pricing issues. If the weather is good and yields continue to boom, farmers should be OK, she said. But if producers have a bad year like 2012 and yields are crimped, food prices could be a problem for the entire country when coupled with the additional costs.

But within four to six years, the sector and rural communities should be returned to some sense of normalcy, and in the meantime, big benefits are being seen by landlords with spiking cash rent for their ground and farmers who are retiring strong to lease out their land and drive trucks for others.

Tough Row to Hoe

The last two years have been interesting to say the least and it would appear that the next two could be just as challenging. According to the Purdue survey, supply chain concerns among farmers include more than just machinery and buildings. With 57 percent expecting farm input prices to rise 20 percent or more in 2022, 34 percent expect the prices to go up 30 percent or more. And in January, 28 percent of producers surveyed reported difficulty purchasing crop inputs from suppliers for the 2022 growing season. The price of anhydrous ammonia in Illinois in January 2022 was nearly triple what it was in January 2021, and 27 percent expect their farm’s operating loan to larger this year. Some 69 percent attributed this to the price of inputs.

But in the end, the real crop harvested could be the lessons learned from the pandemic and new technologies that emerge to battle it. Farmers, always the innovators, will come up with new ways to deal with the prices as in years past. But there’s no question, even years from now, people will still be talking about the impact COVID-19 had on agriculture in America.

Brian Boyce is an award-winning writer living on a farm in west-central Indiana. You can see more of his work at http://www.boycegroupinc.com/.