Changes in the Earth’s climate have trees of various species picking up roots and ready to leave. This means is the forests and orchards of today will look very different just a few decades from now. The changes involve both rainfall and temperatures, and it doesn’t take a forester to recognize how sensitive trees can be to both.

The issue is so pressing that it is leading universities and government researchers alike to sound the alarm. The U.S. Department of Agriculture projects that the traditional plant hardiness zones Nos. 3 through 10 will actually continue an upward and slightly westward shift through the year 2099, with the northernmost No. 3 completely leaving the U.S. and No. 11 entering up from the Caribbean. And along the way, entire regions within the North American continent will experience an upward smudging, leading some trees to extinction and others several states out of place.

Meanwhile, almond farmers in California are pulling land out of production due to the ongoing drought. For agriculture and timber producers alike, significant changes are coming even within the generation as all across the North American continent, the mini seeds blown from live trees to the ground are remaining dormant until bounced across more suitable grounds, miles and then states away.

The long-term results of these changes are staggering, not just in economic terms, but ecological. More wildfires in areas historically unaccustomed to them, a migration of new pests and beetles into areas in pursuit of the moving tree species, and different qualities of timber are all just a few things set to occur in the near future.

Why is this happening?

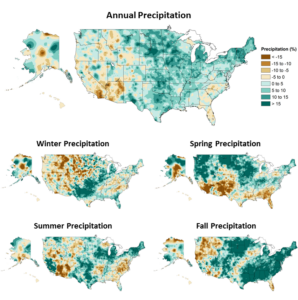

According to the U.S. Global Change Research Program in its Climate Science Special Report, annual precipitation averaged across the entire U.S. has increased about 4 percent between 1901 and 2015, but the differences in regional and seasonal precipitation volume is considerable. Precipitation levels have increased in the Northeast, Midwest, and Great Plains while decreasing sharply in the Southwest and to a lesser degree in the Southeast.

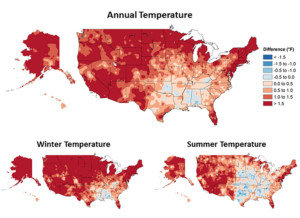

Meanwhile, the average temperature in the contiguous U.S. has likewise increased, with a much greater degree in the Southwest and Great Plains as opposed to the Southeast. Simply put, the tree species in place are no longer welcome in their native environment. A fully mature tree can endure these slight changes, but the tiny seedlings dropped into the soil are finding hostile temperatures and moisture contents. Too hostile to take root.

Not that any of that is news to those in the agricultural fields. But the results are adding up when it comes to trees and other plants. The phenomenon at hand has been a long time coming with ecologists watching it progress over years.

One study conducted by researchers at Purdue University tracked the shifting distributions of 86 different types of trees across all states using U.S. Forest Service Forest Inventory and Analysis Program from 1980 to 1995 and 2013 to 2015. The team reported significant shifts in the centers of abundance for those types over the past 30 years, with 30 percent showing great poleward shifts at an average rate of 6.8 miles per decade. Some 47 percent made statistically significant westward shifts at 9.6 miles per decade. There was little movement south or east reported. To that degree, the researchers concluded this movement was more due to precipitation changes rather than temperature, although both variables are related.

Historically one was accustomed to seeing citrus trees down south and apple trees up north. But as the temperatures and ground moisture change, so will the composition of plant life in those zones. To that end, some more drought-tolerant trees are literally migrating by way of their seedlings. Whether carried by birds, wind, or other animals, the migration of the trees is an example of natural selection at its finest as the seeds take root in the soils best suited them.

And of course as each generation of trees begins to produce new seeds, those too continue the march north by northwest, one after another.

Potential impact for agriculture

Trees are more than just producers of nuts, fruits, and timber, but let’s face it, that’s a considerable contribution to the ag-economy. But what’s equally concerning is the role trees play in converting carbon dioxide into oxygen, and the cooling effect they have on their surroundings. Long-term, changes of tree species in a geographic zone will affect the nature of the zone itself. Different tree species also attract different types of wildlife and play host to different pests, fungi, and diseases.

As the tree species move, so does the entire ecosphere it seems. And along the way, it’s possible that entire species of trees could go extinct as their seedlings cannot migrate fast enough.

But back to the nuts, fruits, and timber. Research affirms what all farmers likely already know: Extreme weather impacts crop quality, and the same is as true for apples as it is for corn and soybeans. Parts of the country long known for the production of tree fruit will have to adapt, and perhaps even abandon those pursuits in a much shorter time frame than expected. The issue is such that the U.S. Department of Agriculture has created its own Climate Change Tree Atlas online. Adaptation projects on both public and private lands range from watershed projects to beaver habitats.

Producers and landowners alike need to be aware of these changes as they occur, working this knowledge into future plans. The good news is there might be new uses for lands previously underutilized, but unfortunately that goes both ways, and mighty challenges loom for operations already in place.

Brian Boyce is an award-winning writer living on a farm in west-central Indiana. You can see more of his work at the Boyce Group homepage.