There is no doubt that wherever you may fall within agriculture, pollinators are one of your key players. Whether you raise crops or cows, indoors or out, you need pollinators. Yet these fuzzy insects are too often taken for granted — their health and questions over whether pollinators are going extinct are vital to address.

For decades now we have been watching our pollinator population decline due to a number of factors, including the changing climate, predators, habitat obstruction, and pest control on crops, gardens, and lawns.

In 2014, then President Barack Obama enacted the Federal Pollinator Task Force, which is co-chaired by the Environmental Protection Agency and the U.S. Department of Agriculture. The goal of this was to restore the populations of native pollinators and to restore or enhance 7 million acres of land for pollinators across the U.S. So, each U.S. state had to come up with a plan to contribute to this goal.

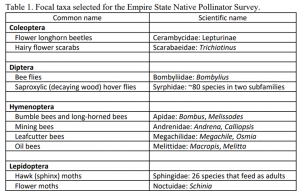

In June 2022, the Empire State Native Pollinator Survey summary was published on the New York Natural Heritage Program website, and it found that of the 10 insect groups studied, that at least 38 percent (and up to 60 percent) of them are at risk of extirpation from New York.

This sounds pretty scary, but this 38 percent to 60 percent of the insect population at risk was only in the very small portion of New York’s native insects studied, and the insects studied were all assumed to be at risk of extirpation before the study even started.

Growing up surrounded by agriculture in the lovely Upstate New York, I wondered what the consequences of these findings might be. In the U.S., New York is the second highest apple producer, fourth top grape producer, and the second top cabbage producer, among its other large outputs like blueberries, cauliflower, and hay. Because all these crops directly depend on pollinators, were these crops at risk too?

I talked with Maria Van Dyke, the manager of Cornell’s Danforth Lab of Entomology. Van Dyke is passionate about pollinators, specifically bees. She said that they didn’t find any specific crop or plant family that was at a real risk of extinction because of the declining pollinator population. But that doesn’t mean we are in the clear, it’s important for everyone to learn about pollinators and what we can do to help them.

What is interesting to note is that some pollinators are picky eaters, while others will eat most anything in front of them. Monarch butterflies are known for their love of milkweed, and they will only eat from the milkweed plant family, so Monarchs are considered a specialist. Whereas the honey bee will consume the pollen and nectar from many different plants, so they are considered a generalist.

Specialist pollinators might be picky eaters for various reasons. Think about our squash bees; these squash bees are originally from Central America, just like squash. As people moved north from Central America, they brought squash along the way, and the bees were quick to follow. Soon enough the New York became a huge squash-producing state, and we have squash bees galore! Squash bees evolved to consume nothing but squash.

Some species have evolved with a plant family so that that plant family has everything the pollinator needs. For those of you who always order the same thing at every restaurant, you know how these pollinators feel: If it ain’t broke, don’t fix it!

And some species just don’t have very many options. Plants such as daylilies and irises grow only in very wet conditions, so they need a pollinator that can tolerate that. Plants such as cacti and yucca like a hot and dry environment, so they need a pollinator that likes that too. We also need to remember that our pollinators aren’t out and about all year long — some only buzz in the spring, and some only in the fall, while some seem like they never go away.

So when it comes to helping the pollinators, you can’t plant any old thing. The best way to support your local pollinators is to plant native plants. Van Dyke and her colleagues at Cornell University published a guide to creating a pollinator garden to help you understand what your pollinators need. A guide that I love is one by the Xerces Society on what plants are native to your area and what needs they have.

Beyond the pollinator gardens, we also need to tighten up our Integrated Pest Management (IPM) protocols. You wouldn’t put a band-aid on your knee because you might fall down today, right? So we also shouldn’t apply automatically pesticides to our fields or gardens just because they could have pests. Tightening up application at the edges of our lawns, gardens, and fields also can have a huge impact on pollinators. Diminishing or eliminating the drift of insecticides and herbicides is something we need to strive for.

Because pollinators are crucial to all of us in agriculture, we have to start thinking about them more. Whether that’s through implementing new IPM protocols or planting a pollinator garden in the yard, we need pollinators more than they need us.

Elizabeth Maslyn is a born and raised dairy farmer from Upstate New York. Her passion for agriculture has driven her to share the stories of farmers with all consumers, and promote agriculture in everything she does. She works hard to increase food literacy in her community, and wants to share the stories of her local farmers.