Antimicrobials have made headlines in agriculture for a long time, and usually not positive ones.

Especially for people removed from agriculture, the industry has become an easy scapegoat for the devastating effects that antimicrobial resistance has had — or could have — on human and animal health. But have “antimicrobial” and “agriculture” become synonymous due to actual misuse, or rather because of misunderstanding?

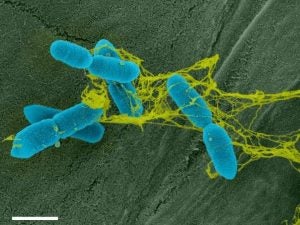

First off, we have to know what antimicrobial resistance actually is. According to the World Health Organization, antimicrobial resistance is what happens “when bacteria, fungi, viruses and parasites no longer respond to antimicrobial drugs.” Which means that if antimicrobial drugs are overprescribed or underdosed, bacteria and viruses can learn to combat the drugs that are supposed to kill them.

This is a major concern because many bacteria, viruses, fungi and parasites that we don’t even shake a stick at right now could become a big health threat.

The WHO states that urinary tract infections, which are very common and often caused by E. coli bacteria, are becoming harder to treat with standard prescriptions. In 2020, the WHO found that 20 percent of UTI cases showed reduced susceptibility to common antibacterial drugs.

But where did agriculture and antimicrobials begin their tumultuous history?

It’s safe to say that when antimicrobials exploded in popularity in the mid 1900s, they were overused — judging by what we now know. Putting antibiotics in feed or water allowed farmers to prevent common diseases rather than have to treat them later — it was a preventive rather than curative approach. Animals were never given a chance to get sick and ended up growing quicker, bigger, and healthier.

This widespread preventive use of antimicrobials gave agriculture a very bad rep when it came to drug use. As new research comes out about how antimicrobials work and should be used, farmers follow the new guidelines under their veterinarian’s consent and guidance.

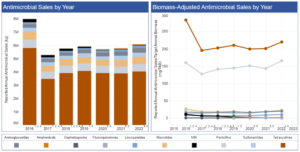

Fast forward to 2023, and antimicrobial use in agriculture has gone down exponentially. As an industry, we shifted from using antimicrobials in a broad-based way to using them on a targeted and case-by-case basis.

Graphs from the FDA show that antimicrobial sales compared with livestock inventory have declined significantly since 2015, which was a peak year in antimicrobial sales.

In 2023, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration’s Center for Veterinary Medicine published guidance on the availability of antimicrobials, making antimicrobial drugs no longer available over the counter for farmers. This change wasn’t a big deal for many farmers, as they get all their treatments through vets, but this did impact some farmers who used to be able to pick up common antimicrobials at their local farm supply store.

The reason for this change is because public health experts such as those at the Infectious Disease Society of America feel that if society doesn’t crack down on antimicrobial use, antimicrobial resistance will continue to cause severe effects on human and animal health.

Now here is where the turmoil starts.

The IDSA states on its website that “the relationship between antibiotic-resistant infections in humans and antibiotic use in agriculture is complex, but well-documented. A large and compelling body of scientific evidence demonstrates that antibiotic use in agriculture contributes to the emergence of resistant bacteria and their spread to humans.”

Claas Kirchhelle, a “bugs and drugs” history buff and professor at the University at College Dublin in Ireland, wrote a book, called Pyrrhic Progress, about antimicrobial use in agriculture. While this book is mainly centered on British farms, it lands a few jabs at the U.S. too. The first chapter, titled “The sound of coughing pigs,” tells a tale about the need to use antimicrobials in agriculture, while the next few chapters — “Picking one’s poison,” “Chemical cornucopia,” and, my favorite, “Toxic priorities” — outline how antimicrobials exploded in popularity, and the prioritization of problem solving when we realized the effects that mass use of antimicrobials could have.

For us farmers, it feels like we are being blamed for antimicrobial resistance. We used antimicrobials that were marketed toward us and now we have to pay the price?

Agriculture feeds the world, and people don’t want to be scared of what they’re putting on their plates. Sure you should question the medicine you put in your body, but nobody wants to obsess in that way over the food they eat.

Hang with me, we’re turning up the turmoil!

Today’s farmers and ranchers are already doing a great job of being conservative with antimicrobial use, but what is the problem when you can buy antimicrobials over the counter? The FDA has no record of who bought them and why. With antimicrobials being sold exclusively under prescription, the FDA can track where things are going, how much people are using, and there’s an increased confidence that they are being used correctly since they are only handed out by a veterinarian with known professional training.

But the problem isn’t that farmers don’t know how to responsibly use antimicrobials, it’s that because of the potential for antimicrobial resistance, we truly have a limited time with the antimicrobials at our disposal — the can too quickly become no longer effective enough to rely on.

There’s a phenomena in the medical world called the “discovery void,” which was a period of time between about 1987 and the mid 2000s where there were no new antimicrobial classes hitting the pharmacies.

Antimicrobial classes are the “base” of the antimicrobial. You can compare antimicrobial classes to flour we use as a base for baking. We have wheat flour, then we have enriched flour (that’s still wheat), and we have whole wheat flour (still wheat), and many other types of flour that are all wheat. You can make a million different kinds of bread with it, but wheat is wheat, and that’s what we’ve got.

To put that into better perspective … the flu shot is different each year because the viruses that cause the flu aren’t the same year to year. Yet we’ve been using the same handful of antimicrobial drugs for over 30 years?

The WHO addressed this in a 2022 article, stating that since 2017, 12 new antimicrobials have been approved for use, but 10 of them belong to the same class.

In the same article the WHO writes, “It currently takes approximately 10-15 years to progress an antibiotic candidate from the preclinical to the clinical stages. For antibiotics in existing classes, on average, only one of every 15 drugs in preclinical development will reach patients. For new classes of antibiotics, only one in 30 candidates will reach patients.”

Let’s go back to agriculture now. Agriculture has a sticky history with antimicrobial use, and we’re fixing it. But we are at the mercy of medicine. We have to be extra cautious with antimicrobial use for two reasons. First off, it would be irresponsible to misuse antimicrobials; and secondly, we are producing food for the everyone, so we play a huge role in antimicrobial resistance across the world.

Amid all of this, it’s important to recognize that while penicillin for a cow and a person are of the same class of antimicrobial, the formula in the drug is going to be a little bit different. So if we have penicillin-resistant cows, it is thought that it can have an effect down the road if people are consuming their meat and milk.

It is not clear exactly how antimicrobial resistance in animals is affecting resistance in people, but what we do know is that there are never antibiotic residues present in animal products. Animal products are tested for residues before they’re allowed to be processed, which keeps our food supply safe.

This happens, in part, because antimicrobials available on farms come with a defined “withdrawal period,” which tells the farmer how long the antimicrobial stays in an animal’s system for. Check out the label for a drug called Duramycin (tetracycline class), which states that a cow’s milk is safe for consumption 96 hours after treatment, and her meat is safe for consumption if slaughtered 28 days after treatment. These guidelines help farmers make decisions on treatments for animals.

There are also “antibiotic like” compounds called ionophores used in some livestock feed that are not related to human health because they affect only naturally occurring bacteria in the rumen (the rumen is the main stomach compartment of ruminants such as cows and goats). These ionophores promote the bacteria that create more available energy for the animal, making them require less feed for more efficiency.

While these ionophores sound a little weird, there’s a lot of research being done on how to play with bugs in livestock bellies to achieve efficiency and even environmental goals. As the dairy industry moves toward its goal of being net zero by 2050, there’s a push to use feed additives that essentially inactivate the bugs in cows’ guts that make methane. These ionophores do not affect people, and therefore aren’t “medically important” for humans.

It’s up to us to continue to improve our use of antimicrobials, and push for more research to be done on them. It’s also our responsibility as farmers to reduce our need to use antimicrobials. With clean facilities, feed and water, and progressive vaccination protocols, there should be fewer sick animals. The better we do to prevent disease and illness, the less we will need to use treatments.

To understand more about antimicrobial resistance, don’t hesitate to chat with your veterinarian and local extension experts. For now, we have to follow increasingly stricter restrictions on antimicrobials because of the bigger picture, it’s a crisis beyond us. We have the ability to change the antimicrobial story by supporting the effort to end microbial resistance.

The U.S. Department of Agriculture addresses many frequently asked questions and has links to research on its antimicrobial resistance overview page, which is a great resource for keeping up to date.

Elizabeth Maslyn is a born-and-raised dairy farmer from Upstate New York. Her passion for agriculture has driven her to share the stories of farmers with all consumers, and promote agriculture in everything she does. She works hard to increase food literacy in her community, and wants to share the stories of her local farmers.