What’s at stake when we pave over, fragment, and otherwise fail to protect farmland from the disruptions of development?

Millions of acres of America’s agricultural land were developed or converted to uses that threaten farming between 2001 and 2016, according to “Farms Under Threat: The State of the States,” a comprehensive new report by American Farmland Trust. The 68-page report’s Agricultural Land Protection Scorecard is the first-ever state-by-state analysis of policies that respond to the development threats to farmland and ranchland, showing that every state can, and must, do more to protect their irreplaceable agricultural resources.

“The State of the States” report shows the extent, location, and quality of each state’s agricultural land and tracks how much of it has been converted in each state using the newest data and the most cutting-edge methods. The Agricultural Land Protection Scorecard analyzes six programs and policies that are key to securing a sufficient and suitable base of agricultural land in each state and highlights states’ efforts to retain agricultural land for future generations. It offers a breakthrough tool for accelerating state efforts to make sure farmland is available to produce food, support jobs and the economy, provide essential environmental services, and help mitigate and buffer the impacts of climate change.

Agricultural lands are essential to a more resilient America that is better prepared for crises.

Farmland is vital to this nation’s food security, yet it continues to be paved over, fragmented, or converted to poorly planned residential, commercial, and industrial uses. Between 2001 and 2016 alone, 11 million acres of the nation’s irreplaceable agricultural land was lost or fragmented, equal to all the land in the U.S used to produce fruits, vegetables, and nuts in 2017. Roughly 4.4 million of these acres were “Nationally Significant” — our best land for food and crop production.

Because of the COVID-19 pandemic, millions of Americans have seen empty grocery shelves for the first time in their lives. We have come to realize how critically important farmers are to us, how we turn to them in crises, and how they innovate to meet demand. But they can’t do their job and we won’t have sufficient healthy food without farmland.

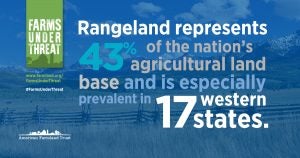

The U.S. holds the world’s greatest concentration of fertile soil suited for growing food and other crops. However, only 39 percent the agricultural land in the lower 48 states is defined by AFT as “Nationally Significant” land, which can reliably produce abundant yields for many decades to come, if farmed sustainably.

Each state needs to secure a critical mass of high-quality farmland to ensure that its food system is resilient in the face of extreme disruptions. After all, what is more essential to human life and society than healthy food? We need agriculture, especially environmentally sound “regenerative” agriculture, to survive. As a nation, it will take regionally diverse and sometimes redundant systems to support the increasingly complex public demands on agriculture. All states must act to protect farmland.

The 12 states with the most threatened agricultural land are:

1) Texas 2) North Carolina 3) New Jersey 4) Tennessee 5) Georgia 6) Rhode Island 7) Connecticut 8) South Carolina 9) Massachusetts 10) Delaware 11) Florida 12) Pennsylvania

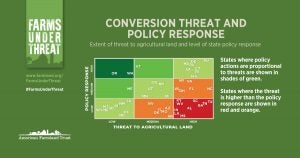

Action is particularly urgent in the South where threats are high, but policies are limited.

Farmland is at severe risk in the South, where agricultural land is being urbanized and converted to low-density residential land use at a rapid pace. Six of the top 12 states with the most threatened agricultural land are in the South, according to the report.

Importantly, states in this region of the country have often enacted fewer public policies to protect agricultural land. States in the South that were identified as having a high degree of threat and low policy response include Texas, Georgia, Kentucky, Tennessee, South Carolina, Alabama, Mississippi, and Louisiana. There is a particularly critical need for state policymakers to act in these states.

Urbanization slows, but a new threat comes into focus.

Since 2000, a combination of economic conditions, changing consumer preferences, planning practices and public policies have slowed urbanization. Even so, agricultural land is still being converted to urban and highly developed, or UHD, land uses nationwide. Between 2001 and 2016, 4 million acres were lost to the expansion of urban areas.

What’s more, the Farms Under Threat research captures a new class of land use: low-density residential, or LDR. LDR land use occurs where the average housing density is above the level where agriculture is typically viable. It includes large-lot subdivisions, open agricultural land that is adjacent to or surrounded by existing development, and areas where individual houses or housing clusters are spread out along rural roads.

Low-density residential land use threatens working farms and ranches by fragmenting the landscape and disrupting agricultural economies. In just fifteen years, nearly 7 million acres of farmland and ranchland were converted to LDR land use.

We all recognize urban sprawl, but low-density residential land use has flown below the radar, even though it is just as much of a threat to farmland — now and in the future. Indeed, the report shows that LDR paves the way for further urbanization. Agricultural land in LDR areas was 23 times more likely to be converted to UHD than other agricultural land. In other words, once land has been converted to low-density residential land use, new development rapidly occurs on the remaining farmland and ranchland in the area.

LDR land use compromises opportunities for farming and ranching, making it difficult for farmers to get into their fields or travel between fields. New residents not used to living next to agricultural operations often complain about farm equipment on roads or odors related to farming. Retailers such as grain and equipment dealers, on which farmers rely, are often pushed out. Farmers can be tempted to sell out for financial reasons, or because farming just becomes too hard in the circumstances. And lastly — but importantly — as older farmers near retirement they sell their properties, too often to non-farmers. This means that new and beginning farmers have a hard time finding land, threatening the very future of agriculture. More often than not, the land prices in these areas have been driven up by the encroaching development making it impossible for new farmers to afford to buy a farm.

What can states do to protect our nation’s irreplaceable farmland?

The report found that every state in the nation has taken some action to protect agricultural land, but all states must do more. Combined, states have permanently protected more than 3 million acres, secured more than 40 million acres with restrictive covenants and zoning, and reduced the tax burden on more than 475 million acres helping them remain viable for agriculture. The report examines six approaches that help protect land and maintain thriving agricultural communities — PACE programs, land use planning policies to manage development, agricultural districts programs that protect and encourage commercial agriculture, property tax relief for agricultural land, state leasing programs making state-owned land available to farmers and ranchers, and FarmLink programs that connect farmers with available land.

The report’s Agricultural Land Protection Scorecard shows where policy is having an impact and where more needs to be done, comparing threat to policy response.

Committed state action is an essential response to the loss of farmland and ranchland. While municipal and county governments are often in the best position to assess local conditions and address local needs, their resources often are limited, and the decisions in neighboring communities can have an impact on entire regions. State (and federal) goals and funding are needed to strengthen local efforts.

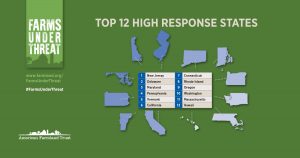

Pursuing multiple approaches and linking them together is the most effective path. The 12 most proactive states implemented a mix of approaches. Most significantly, they linked their programs to enhance effectiveness and created state guidelines to ensure local actions achieve broader goals.

The states with the most proactive policy responses to farmland protection are:

1) New Jersey 2) Delaware 3) Maryland 4) Pennsylvania 5) Vermont 6) California 7) Connecticut 8) Rhode Island 9) Oregon 10) Washington 11) Massachusetts 12) Hawaii

What will AFT do to protect our agricultural resources?

AFT will act to double permanently protected farmland by 2040 and reduce the rate of farmland conversion by half by 2030 and by 75% by 2040, making our best land a priority.

“AFT’s goal for saving farmland is ambitious, but it is necessary and doable. The sobering statistics and pressing challenges uncovered in the “Farms Under Threat” research demand action,” said John Piotti, AFT president and CEO. “Meeting this goal will require a rejuvenated farmland protection movement emboldened with new purpose and urgency. For our part, AFT has outlined a five-point strategy to lead this national effort alongside our many partners, including at the top of that list our nation’s farmers and ranchers.”

To save farmland at the scale needed will require a highly effective army of government entities, nongovernmental organizations, and committed farmers and ranchers. As we have for 40 years, AFT will actively support these players, providing information and assistance in numerous ways wherever we can. Specifically, we are taking the following steps:

- Establishing the National Agricultural Land Network, a nation-wide network of land trusts and government entities focused on protecting agricultural lands.

- Providing new leadership in key locations, launching a program in the South and new emphasis in parts of the Midwest.

- Protecting more farmland ourselves and with partners, reinvigorating our conservation easement work.

- Advocating for stronger state and federal policies, helping any states interested in improving their land protection efforts and continuing our work with U.S. Climate Alliance states.

- Promoting research-based decision making, widely disseminating the findings from “Farms Under Threat: The State of the States” report.

AFT will work tirelessly to save the land that sustains us.

Compromising Nationally Significant land imperils U.S. farm viability, the environment and our ability to fight climate change.

The 4.4 million acres of Nationally Significant land that were converted to non-agricultural use between 2001 and 2016 were some of the most valuable land in this country. It can take two to three times the amount of marginal land to make up for its loss. Every state converted high-quality agricultural land — both land significant to the nation as a whole and land significant for local and regional food systems.

When Nationally Significant land is impacted by development, intensive food production is pushed to more marginal lands where input costs are higher, crop yields are lower, and soils degrade more quickly. Farmers are challenged to make an adequate income and risk going out of business.

When farmers have no choice but to farm marginal land, the additional fertilizers, herbicides, and insecticides they use runoff into waterways and increase air pollution.

In fact, when farmland is managed well, it produces far less pollution than land converted to housing or commercial use. According to the study “Greener Fields” produced by AFT and UC Davis, farmland that is converted to other uses emits greenhouse gases at a level 58-70 times greater than if it had remained in farming. To put that in perspective: a 75 percent reduction of farmland loss in California would be equivalent to taking 1.9 million cars off the road.

Well-managed farms and ranches can help cool the globe. But it’s our best land that does this most effectively. The capability of marginal land to sequester carbon is significantly lower than land with better soils. Soils that are paved over, of course, sequester none at all.

Right now, if all of the Earth’s farmers and ranchers implemented regenerative practices on their land—such as reducing tillage, growing cover crops, planting perennials, and enhancing grazing management—the impacts of GHG emissions from fossil fuels could be cut by 10 to 20 percent annually. But when farmland converts to other uses, we lose land that could have sequestered carbon. What’s more, additional pressure is put on the remaining acres to be farmed more intensively, limiting our opportunity to farm in ways that benefit the environment. It’s a vicious cycle. Taking it a step further, the benefits of regenerative agriculture are temporary unless the farmland on which the practices are undertaken continues to be stewarded wisely. If the farmland is ultimately lost to development, much of the carbon that had been stored in the soil will be re-released to the atmosphere.

We only have a decade to stop the worst impacts of the climate crisis — we need to preserve every acre of our best soils.

We know that in addition to development pressure, farmland is under pressure from the impacts of climate change. In the next phase of ‘Farms Under Threat’ research, AFT will be looking at climate impacts on the land, projecting out to 2040.

As the worsening impacts of climate change continue to raise ocean levels, saltwater intrusion will take away coastal farmland and populations will be driven inland, pressuring more farmland. Changing weather will render some farmland too wet to farm, while other land will be too dry to be productive.

Being prepared means protecting farmland now. What seems abundant in the present may not be adequate in the future.