As summer and fall fairs close across America, the sight of empty halters in barns once bustling with livestock projects can stir deep emotions. These symbols represent more than just the end of the show season — they embody the life lessons young people learn along the way. Whether through social media posts or reflections at home, families hail the youngsters who discover how to win and lose with grace, set and pursue goals, and nurture another living being.

These empty halters also represent the larger lesson of what it truly means to raise livestock for a purpose. Beyond ribbons and trophies, kids are learning the full scope of the food production process: the care, effort, and emotional investment that goes into raising an animal destined to become food for someone else. This understanding is vital. Without it, the money spent on showing livestock risks being reduced to an expensive beauty contest, disconnected from the agricultural roots it stems from.

As a former extension agent and 4-H educator, I’ve observed firsthand how some parents approach the topic of life and death in livestock projects. Most would rather gloss over these things for their children, and possibly they want to shield them from the emotional cost of the experience.

Their hearts are pure at least, and this bypass can create a division between the reality of farming and the things children can gain through it.

If children are not given the opportunity to be engaged fully in the life cycle, they might lose out on valuable lessons of responsibility, compassion, and the significance of food production. Talking about these in an open manner can help children form a better picture of agriculture so they can better enjoy the life skills gained from their projects along with struggling with the undeniable truths of life and death. By developing this awareness, we are not only educating young people for their roles in agriculture, but also enabling them to deal intelligently with the external world.

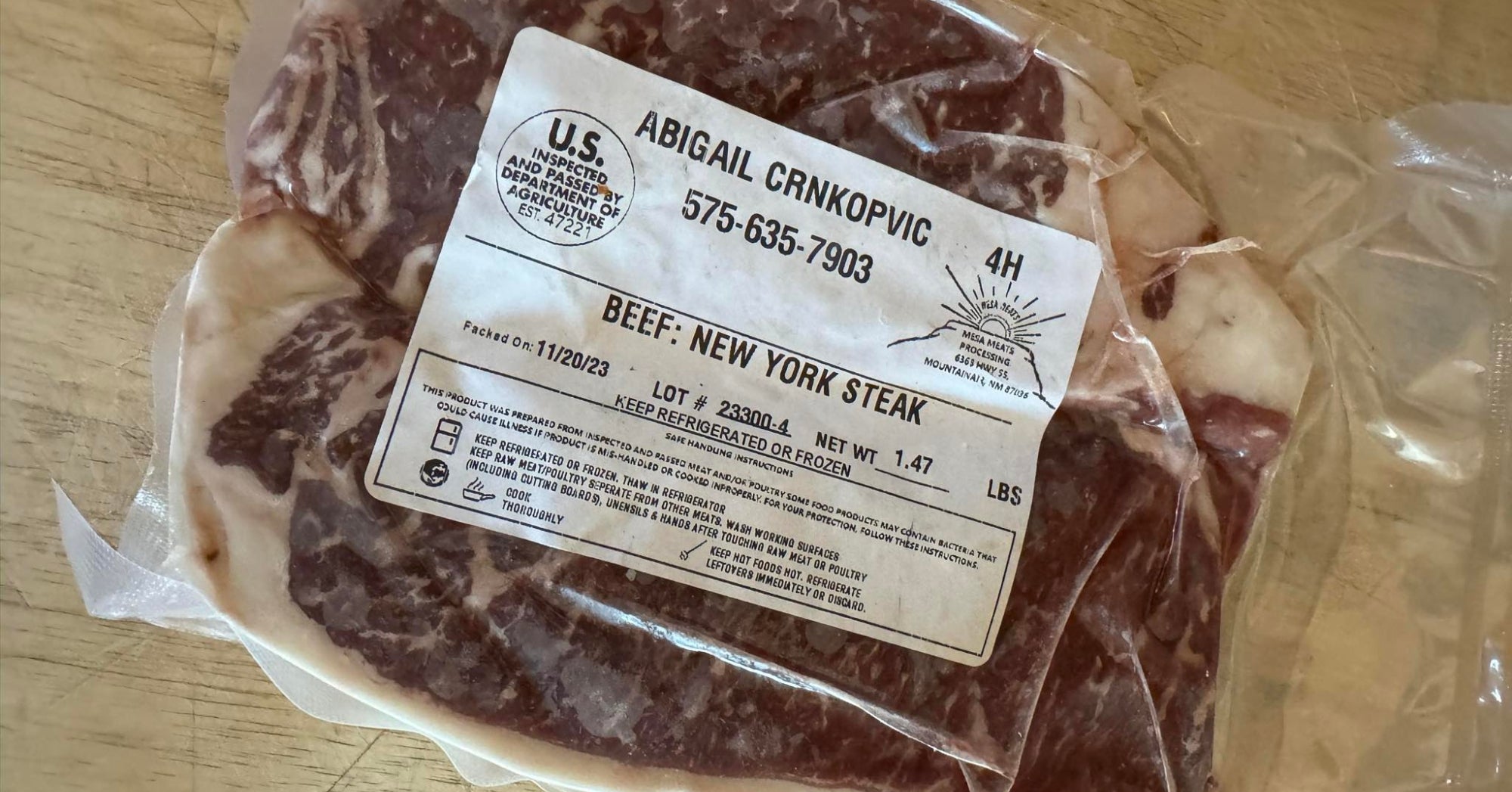

This was my daughter’s third year showing livestock, and each year, a few of her animals leave on a packer truck — some head to a custom processor in town, while others are sold as breeding stock. But this year was different. For the first time, she loaded her own calf onto the truck — by choice.

I hadn’t asked her to, but as I stood there with a heavy heart, she calmly walked her yellow calf into the trailer, said “thank you,” and “goodbye,” while a few adult volunteers also shed tears. It was a proud moment to see an 11-year-old girl embrace one of the more difficult lessons of raising livestock: respect to the animal and the system it belongs to.

It was made more poignant by what she learned along the way. This year, alongside of feeding and raising her animals, she learned about primal and subprimal cuts of beef, taking the time to create a poster that outlined these cuts and the products derived from them.

It was displayed for the public to see, helping to educate others about the journey from farm to table. Understanding where food comes from is critical, and through this, she was able to help others make that connection.

Showing livestock exposes young people to the full circle of life. In a society where many avoid discussing or preparing for death, kids in agricultural programs are directly involved with raising animals they will eventually sell, often for meat. This hands-on experience prompts them to confront the realities of life and death, something that many Americans, as studies suggest, tend to shy away from.

In the past couple of years, the COVID-19 pandemic created global panic and fear because it brought people to the brink of death on a large scale, something that was foreign to so many people. Shortly following the pandemic, Caring.com stated that 67 percent of adults lack estate planning documents, which shows a prevalent failure to plan for death, something that is different from the early exposure to life cycles that farm children experience.

Meanwhile, a 2017 CBS News poll found that 54 percent of Americans avoid death-related thoughts, in line with a general social trend of discomfort with discussing mortality. Likewise, just 33 percent of Americans have a will, with significant variations by age, marital status, and socio-economic status, a 2023 Gallup Poll found.

By raising an animal and then participating in selling it, children learn that death is a part of the cycle of life — an unavoidable aspect of agriculture and food production. Contrary to the greater American trend to avoid mention of death, these young showmen are taught to consider it a necessary, honorable process. This lesson allows them to build emotional resilience, not just to farm life, but also to dealing with adversity in the rest of their lives where persistence is key.

So how then do we communicate to a general public so removed from livestock production and, oftentimes, conversations about life and death? There’s a balance between education and sensitivity, keeping in mind the public’s diverse perspectives on life, death, and food production.

4-H and FFA members are in a unique position to showcase the educational value of these livestock projects. For instance, when my daughter worked on her poster demonstrating the primal and subprimal cuts of beef, she wasn’t just learning about the parts of an animal. She was learning responsibility, perseverance, and gaining respect for the food system.

Sharing these experiences helps frame the message in a positive light, showing how youth programs teach important life skills while contributing to their communities.

It’s also important to balance the talk about livestock and death. Death is a natural component of the process, yet it is not the sum total of the experience. Livestock projects are about hard work, dedication, and the bond that forms between the youth and their animals. By highlighting the compassion and care that is involved, we can show that the production of animals is as much about the nurturing of life as it is about the cycle of food production. My daughter’s ability to put her calf on the truck was not about saying goodbye but about her understanding of her role as a caretaker.

It is also crucial to understand that people have different perceptions of food production. Some are even uninformed or uncomfortable with the realities raising animals for food, and yet more are morally opposed to livestock operations. As both adults and youth exhibits, it’s important to have these conversations respectfully and candidly, with the understanding that although we hold these experiences so dear, others may see them differently.

By sharing our own stories judiciously and explaining the emotional learning and life skills gained, we can invoke understanding without being gratuitously graphic or dismissive.

That’s all to some degree dependent on leadership. 4-H and FFA members are not just learning about raising livestock, but also how to moderate discussions concerning them. In teaching and sharing their experience, and what they’ve learned, they’re in a position to educate others not only about food production, but also about ethical, responsible practices that promote animal welfare and human health.

Through these reflective actions, young livestock producers gain respect and understanding, and are able to educate the public on the value of farming. Through the practice of those leadership skills they also learn through livestock projects, which can even encourage a new generation to study and engage in the agricultural industry.

Finally, it’s important to remember the bigger picture. What we learn from livestock projects doesn’t stop at the fairgrounds — it relates to broader discussions regarding food security, sustainability, and how agriculture contributes to feeding our communities.

If we associate our livestock experiences with these fundamental issues, we can help others recognize the value of raising animals not just for our own self-interest, but for the broader benefit of society.

Heidi Crnkovic, is the Associate Editor for AGDAILY. She is a New Mexico native with deep-seated roots in the Southwest and a passion for all things agriculture.