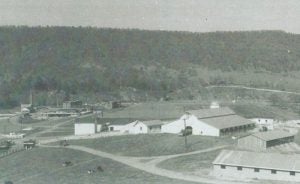

If the people working on this more than 2,100-acre farm in Southwest Virginia weren’t decked out in orange shirts and striped denim jeans, you probably wouldn’t think twice about what you were seeing. There’s 965 head of cattle; fields of cabbage, turnips, and butternut squash; and greenhouses packed to the ceilings with thriving tomato and cucumber plants.

It all seems pretty typical of the kinds of ag operations that are found in this state’s rolling hills.

Yet, it’s the field workers themselves that make this place, Bland Correctional Center, stand out. Stretching well beyond the guard towers and barbed-wire-topped fences is a farm that helps to feed inmates across Virginia and gives offenders a chance to do something worthwhile, to learn a skill, and to be better citizens upon their release.

“It’s beneficial for the re-entry process for these guys. They get a structured lifestyle, which a lot of them don’t have to start with,” said Larry Rasnick, Bland’s Assistant Warden. “They get up, go to work, after work they come back in — their lives are on a schedule. Plus, it gives them a sense of accomplishment. They’re worth how they feel, and they feel good about what they’re doing on the farm.”

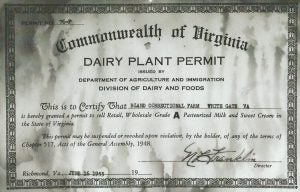

Bland Correctional Center has had an on-site farm since June 1946 and is now one of 24 prisons around the state helping to supply ingredients and meals to other facilities.

“It started out decades ago as Bland and only some of the other facilities nearby, but today, we’re growing lots more crops and trying to keep the food costs down for the whole state,” said Alan Strock, a 45-year-long employee at Bland and the current Agricultural Manager.

How much are we talking about exactly? Just to name a few, there’s:

- 256,400 pounds of spring and fall cabbage

- 14,000 pounds of green peppers

- 59,000 pounds of squash

- 94,500 pounds of potatoes

That’s in addition to the cattle, of which the center keeps an average of 400 brood cows and 80 replacements. There’s about 20 tons of corn silage made, and nearly 3,000 round bales produced.

All of this is done by inmates who primarily grew up in cities and, perhaps surprising to many of us, may not have had even the basic knowledge of how to start a lawnmower.

To turn them into skilled farmers, “We have to teach from the ground up,” Rasnick said.

Of course, there are certain qualifications that an offender has to meet to be able to work outside the walls. The facility houses Level 1 and 2 offenders (Level 5 and Maximum Security are the two highest in the Virginia correctional system), and currently about 60 people are allowed to do farm jobs and other duties at Bland.

“The 1’s here qualify to go outside. They can’t have any violent crimes or any sex crimes, among other criteria. And they have to be under five years of getting out,” Rasnick said.

The prison works with Virginia Tech, the nearby land-grant university, as a site for research and is a regional distribution point for prison system food products — complete with large-scale refrigeration and freezing units and a network of truck drivers.

“We are the hub for getting things delivered in this part of Virginia,” Strock said.

While dairy and sausage production have been handled on site in years past, a major focus today is on packaging pouches of 100 percent juice (apple, orange, and fruit blend), that are distributed throughout the state — and, truly, they are delicious. Soon, the facility will begin making pizzas for distribution.

Even many who don’t work directly in the fields or greenhouses contribute by working on machinery or other production aspects.

“It’s hard to tell how many thousands of dollars that that saves us, just in labor alone,” said Donald Musick, Manager of the beverage plant.

It all gets done at a pay rate of about 35 cents an hour, typically for six hours a day. And there’s room for advancement — skilled laborers can get up to 45 cents per hour.

“A lot of the guys are using forklifts, end loaders, tractors, and other machines — that’s a skill they can use when they get on the outside,” Musick said.

Despite being around for more than 70 years and having permanent farm buildings on site since 1952, there’s virtually no way for passers-by to know that this kind of expansive farming and food production operation exists at the prison.

“Most of the offenders who are working on the farm and in other jobs are ready for the next step,” Rasnick said. “Take farm equipment, for example, that’s a trade in and of itself. They learn to work on engines and other machinery, and knowing that becomes a big asset for them.”

See more historic and modern photos from Bland Correctional Center’s farm below:

Ryan Tipps is the managing editor for AGDAILY. He has covered farming since 2011, and his writing has been honored by state- and national-level agricultural organizations.