Winter wheat is an economically (and gastronomically) important grain crop in North Carolina, producing legions of cookies and crackers and almost $100 million in revenue for the state’s farmers. But Italian ryegrass is an herbicide-resistant weed that plagues winter wheat yields, especially in N.C.’s Piedmont region. In many fields, once the weed appears, it can’t be chemically controlled. N.C. State researchers have successfully drone-identified early-stage Italian ryegrass in winter wheat allowing for wholistic weed management options.

“It’s easy to identify a broadleaf weed in a grass crop or a grass in a broadleaf crop. But there were a lot of questions about whether or not we could differentiate within a grass species,” said Wes Everman, N.C. State associate professor of weed science. “Our aerial imagery was very clear. My team and I quickly realized that we could identify and map Italian ryegrass with up to 96 percent accuracy and early enough to have some management options.”

Studies have shown that Italian ryegrass reduces wheat tillering causing 4 percent yield declines for every ten Italian ryegrass plants per square meter. Up to 80 percent yield loss can occur where high densities of Italian ryegrass exist. If a significant Italian ryegrass population forms, farmers often settle to cut the crop for hay, usually at a lower price.

Additionally, most growers wait until crop prices solidify mid-season before actively managing winter wheat fields, making management with post-emergence herbicides problematic.

Early Italian ryegrass identification opens the door to early-season management techniques beyond herbicides. Cultivation, seed cleaning, and even hand-pulling in small patches would improve wheat crop quality. Even late-stage weed identification could impact management practices for next season like preemergence applications and crop rotation. Knowing where weed populations exist empowers growers to make informed decisions.

Detection at the speed of light

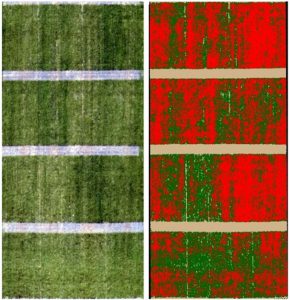

Everman’s research used multispectral sensing to classify ryegrass based on reflected energy from the leaf surface instead of leaf size or pattern shape. With clear skies and midday timing, the team could discern Italian ryegrass in wheat using a drone at altitudes ranging from 15 to 45 meters. The higher flight altitude had no significant bearing on the classification accuracy, allowing a drone pilot to cover larger fields faster, maximizing drone battery life and enabling application in real-world situations.

“While our analyst-guided image classification was almost universally correct, even our computer-assigned image classification was 60 percent to 70 percent accurate. That’s low-hanging fruit showing just how easy it is to train an artificial intelligence classifier for this weed,” Everman said.

And the entire identification process is becoming more efficient. What used to take one to two weeks from field collection to conclusion has now slimmed to a few hours because of improved processing power. And the technology keeps improving.

Refining weed imagery ID

The next evolution in Everman’s research is to classify additional weed species in wheat and eventually tell different weed species apart in any crop.

“Most of the work in remote sensing has been to differentiate between crop and weed. Very little has been done to discern within grass weed species and broadleaf species.” Everman said. “Software companies are refining their algorithms to identify crops and count plants. We could reverse engineer the weed population out of those maps for identification.”

Scouting on the fly

Everman noted that weeds usually affect less than 40 percent of a field and occur in isolated patches, making entire-field treatment unnecessary and potentially counterproductive. Knowing exactly where and when specific weeds appear in a field would allow farmers to select the appropriate management strategy and proactively thwart troublesome weeds.

But field scouting, he noted, is a dying art.

“We can serve our growers by helping them get above their field and see what weeds they have. UAVs are a great entry point for that,” Everman said. “The flying is pretty easy. There are software programs that allow you to just plug into an app and click “go.” The UAV flies the route and comes back to where it started, and it’s done. But the data interpretation — that’s more intense.”

Everman sees an opportunity for Extension to assist growers with the complexities of image collection, processing and interpretation. He proposed training county Extension agents to fly drones for farmers and then collaborate with geospatial expert Rob Austin and himself to analyze the field data for various biotic and abiotic stresses.

Farmers or agronomists could then translate field results into prescription herbicide application files or drone sprayers for precise application.

“Having this type of technology would have been helpful when Palmer amaranth was just starting to invade the Piedmont area. Going forward, we could identify weed species shifts and herbicide resistance creeping in — maybe even different management techniques or chemistries that would extend their longevity. There’s a number of applications this technology could have for our farmers.” Everman said.