In response to the increased use of synthetic fertilizers in modern agriculture, alternative production methods are often discussed and, in some cases, gaining popularity. The organic movement, for example, has championed the use of compost and other non-synthetic fertilizers and pesticides across a broad range of production. Similarly, biodynamic farming has mustered up a strong grass-roots following, though as with other growing methods, there is no one-size-fits all approach to doing what’s best for the soil and for production. So many may ask if biodynamic farming is feasible for their operation and whether it’s accessible. Or, perhaps more to the point, what even is biodynamic farming?

Biodynamic production became popular in the early 20th century when Rudolf Steiner gave lectures on agriculture in response to the soil fertility crisis in Europe. This method of production was a sort of “holistic” approach based on treating the farm as a single organism and focused on a balanced management of agricultural products (plants and livestock). There is also a cosmological and lunar component to biodynamic agriculture, which has associated it with some elements of pseudoscience.

Research of the biodynamic method of production is mostly limited to the organizations that have a vested interest in it. One such organization is Demeter International, which is a biodynamic certifying authority for producers and growers. The widely embraced concept that healthier soil creates healthier plants is good for both the consumer and the environment. However, it isn’t yet clear — based on peer-reviewed research pertaining to the health of soil and crops — whether biodynamic preparations are making any positive, long-term difference.

Steiner, who lived from 1861 to 1925, was an Austrian philosopher and scientist. In the early 19th century, farmers and other agricultural producers combined chemical and mechanical forms of farm management. It began taking a toll on their soil health and crop yields. The ramifications were dire. Not only were crops failing, but animals were getting more and more unhealthy because land managed for forage was also dwindling in vitality.

A group of farmers contacted Steiner for help, which led to a series of lectures and discussions in 1924 that took place in what is now Koberwitz, Poland — they became the basis for biodynamic agriculture.

The lectures were combined and published for the reference of biodynamic producers. This approach was a reinforcement of the idea of whole-farm management, exploring the farm as a single organism with a closed-loop system. The Biodynamic Association explains that “biodynamics is a holistic, ecological, and ethical approach to farming, gardening, food, and nutrition.”

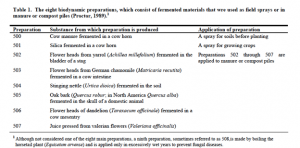

That’s the high-level (if not somewhat generic) view of biodynamic farming. Delving deeper, the idea here is that there should be a farm system that meets its own needs with few, or no, external inputs. This promotes biodiversity, sustainability, and regeneration. There are normally eight preparations, 500-507 (as seen in the table below), and sometimes there is a ninth preparation, 508 (horsetail). You can find more detailed information on preparation requirements in Appendix J of the Biodynamic Farm Standard by Demeter Association Inc., which is organization’s guide for production and certification. The methods of Steiner’s biodynamics also incorporate cosmic events and influences; he coined the term “anthroposophy” to describe the relationship between these and agricultural production.

Biodynamics has become something of a buzzword in the regenerative and sustainable farming world. It’s supported by those who believe in the somewhat mystical qualities of this method to heal the soil and the environment.

And like any trend, especially those related to food, it has drawn a devoted following from celebrities. Musician Sting has adopted biodynamic farming on his vineyards in Tuscany. Arizona Muse, a model turned activist, looked to biodynamic production when she realized that she didn’t know where the materials that went into her fashion garments were grown or processed.

While improving soil health is a sought-after piece of any farming operation, the most romantic notions of biodynamic production is the most prominent aspect that many of its adherents seem to acknowledge.

To her credit, though, Muse is at least attempting to walk her talk by founding DIRT, a nonprofit with the goal of soil regeneration and climate control through biodynamic production. She has published webinars and other videos that discuss finding (and farming) the life force inside of plants, while also speaking negatively of modern agricultural science and its understanding of plant and soil health.

If you’ve ever stood in the middle of a field with plants, trees, and other vegetation, there is certainly an unquantifiable magic to it — perhaps to that extent, Muse is correct.

With the science, however, it’s imperative never to oversimplify scenarios involving the amount of arable land, the scale needed for global food security, and feasibility of farmers to continue generations-long growing operations.

The transition from conventional farming to any other kind of production method, particularly on the scale that many American farmers farm, is expensive and often leads to lower yields — sometimes just for a few years while your growing spaces adjust, while other times, the decline is more permanent (organic, for example, typically has lower yields than conventional production). And there is no certainty that a change will be better for the environment in terms of quantity, toxicity, or management of inputs, or for the farm’s economic situation to be able to keep that land in production.

The transition is also a process that takes several years. Certification requirements include diversity of crops, the addition and management of animals and livestock to the farm organism (with some exceptions), and the dedication of 10 percent of total land to be a biodiversity reserve. Aside from the very small amounts of preparations applied to large amounts of land and/or compost, the spiritual aspect and cosmological practices and events that are used can be off-putting to the non-believer.

“Biodynamic farmers and gardeners observe the rhythms and cycles of the earth, sun, moon, stars, and planets and seek to understand the subtle ways that the environment and wider cosmos influence the growth and development of plants and animals,” the Biodynamic Association says on its website. “Biodynamic calendars support this awareness and understanding by providing detailed astronomical information and indications of optimal times for sowing, transplanting, cultivating, harvesting, and using the biodynamic preparations.”

Farming is magical, it’s true, but it’s also a business, and decisions must be made based on quantifiable and proven information for soil health and yield.

Biodynamics may be the answer, but so far science has not shown this to be true with any statistically significant results.

In a study of biodynamic compost, the results overall found that the preparations seemed to have a small, but not statistically significant, impact on just a few factors that were tested. Compost that was treated with the biodynamic preparations was consistently at a higher temperature. This indicated that there is more microbial activity and it accounts for the compost being more quick to mature.

In another study of the effects of organic and biodynamic management on soil health, it was found that both biodynamic and non-biodynamic compost, when compared to the control, which received no compost or fertilizer, increased soil quality by some of the following factors: soil microbial biomass, respiration (release of CO2), earthworm population and biomass. There were no differences found between the organic and biodynamic treated soil. All indications in this study pointed to organic practices being the factor that improved soil health; there were no indicators of long-term benefits from using biodynamic management.

Using biodynamic methods is money- and time-consuming. They are relatively labor intensive and require a wider body of knowledge on the part of the farmer.

But is it worth it? Does biodynamic farming really work?

Research on biodynamic methods have mixed results, and there is nothing definitive for any part of this production method. Additionally, there is no definitive research showing that a farmer using biodynamic crop management is more financially successful. The certification itself can cost thousands of dollars.

Yet the most difficult part of researching biodynamic methods is that many of the factors are not tangible and, therefore, cannot be reliably measured. Research in biodynamics is limited to those factors that can be reliably measured and practically applied.

There’s a certain cadence that is associated with biodynamic production. Pacing the growing season with lunar cycles, planetary rhythms, and celestial events brings quixotic images to mind, and some people believe there is something to these practices — after all, the Farmer’s Almanac uses lunar phases to dictate planting schedules. Historically, this is how many cultures managed their planting schedules.

Yet biodynamics takes it a step further by creating a relationship between living soil or living plants and the cosmos. How can you measure the effect of a lunar rhythm on preparation 500 on a grapevine? The short answer is that you can’t, and, realistically speaking, if a production method is not proven to be beneficial across a variety of metrics, it may not be worth applying.

Brianna Scott is a veteran farmer who lives in Eastern Washington while earning her Master’s of Science in Agriculture from Washington State University. She is active in the veteran ag community and raises poultry and livestock while growing a large market garden.