For the second year in a row, romaine lettuce has caused an E. coli scare for the Thanksgiving holiday. Besides that, an E. coli outbreak in the spring of 2018 was traced to romaine grown with irrigation water apparently contaminated from a nearby feedlot. Two hundred people were sickened in that outbreak, and five died. The U.S. Center for Disease Control and Prevention says the strain was the same in all three cases, E. coli 0157:H7, which produces a toxin that causes painful cramps, bloody diarrhea, and vomiting. Most people recover in five to 10 days, but 5 percent to 10 percent develop life-threatening complications.

Romaine lettuce has been in the news a lot this last year, but by no means is it the only vehicle transporting foodborne illness. Since January 2018, there have been over 25 recalls by meat companies involving millions of pounds of meat. Not all of these were bacterial related; some were for bits of plastic or metal. In addition to E. coli outbreaks, the CDC estimates 1.3 million people fall ill from campylobacter and 1.2 million from salmonella every year. In total, from 15 different pathogens, the CDC estimates 8.9 million people get sick, 53,000 are hospitalized, and 2,300 die each year in connection with foodborne illnesses. The estimated yearly cost to the economy? $15.6 billion.

Increasing instances of foodborne illness in this century prompted Congress to pass the Food Safety Modernization Act (FMSA) in 2011. It is just now being fully implemented for farms grossing over $500,000. Smaller farms will come under the act in coming years. The Act requires significant borders between fields and possible contamination sources. Irrigation water must be regularly tested for pathogens. These and other requirements are expected to cost growers $25,000 to $50,000 each year. Small farms may not be able to comply. Some of the requirements, such as water testing and borders, were already being implemented by Salinas romaine growers being blamed for the latest outbreak. One wonders if fields of leafy greens can ever be fully protected from pathogens that can move by wildlife, water, and air.

The sad thing is, most of this mayhem could be prevented by a technology that was thoroughly researched in the 1950s but never widely applied. I’m talking about food irradiation. Like so many technologies that could improve the human condition and lessen human impact on the environment (think nuclear power and GMOs, and even vaccines), food irradiation has been subjected to myth and unfounded fears.

Consumers hear or see the word “irradiation” and think “cancer,” “radioactive food,” or damaging molecular changes to the food. X-rays are one method used to sterilize food. We all know X-ray tables don’t become radioactive, and neither does food. Cancer is no more of a threat with irradiated food than with other forms of sterilization, such as cooking or chlorine rinses. Molecular changes do occur, and that’s how bacteria and molds are killed, and spoilage is eliminated or delayed. Cooking makes molecular changes, too. Acrylamide, a carcinogen, is known to be produced when many foods, such as potatoes and meat — foods we all eat — are cooked at high temperatures. Seventy years of researching and testing irradiated foods has proven its safety.

Irradiation of fruits and vegetables was approved by the FDA in 1986. Tests had shown that low dose radiation was effective in killing bacteria, molds, spores and insects while also increasing shelf life. But to date it is applied mostly to imports from Hawaii and foreign countries to enforce quarantines on insects and diseases. Irradiation of meat products has also been legal since the mid-’80s but not routinely found in grocery stores. Mail-order companies such as Schwan’s Inc. and Omaha Steaks have offered irradiated meat since 2000. All non-cooked ground beef offered by these companies is irradiated.

Irradiation of grains and flour has been legal in the U.S. since the 1960s. In the last few years, flour from General Mills and Archer-Daniels-Midland have been subject to recalls due to E. coli or salmonella contamination, both of which could have been eliminated with a small dose of radiation with no change in the appearance, taste, or use of the flour.

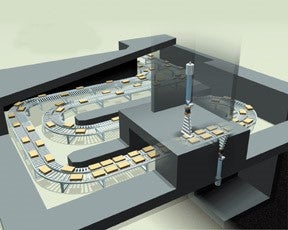

Sixty countries have legalized irradiating of at least some foods. China irradiates more food than any other country. It’s estimated 600,000 tons of food was irradiated in China in 2015, using 140 facilities. The U.S has about 50 facilities, but they sterilize medical devices and supplies as well as food. The volume of irradiated food consumed in the U.S. is second only to China, but most of it is imported from 10 countries plus Hawaii, according to data from 2015. Totals, domestic plus imported, are “68,000 tons of spices, 30,000 tons of fruits and vegetables, 12,500 tons of meat, poultry and live oysters and 10,000 tons of other food items.”

Sounds like a lot of irradiated food. I decided to visit my local Safeway and Super Food stores and see if I could find at least some irradiated imported exotic fruit. When I asked the produce people and the meat people if they had any irradiated products, they looked at me like I was crazy. Never heard of it. I showed the Safeway produce worker a “radura,” the international symbol that should be attached to anything irradiated, and asked him if he had ever seen it. He shook his head, and even took me into their storage area to see if any unopened boxes bore the label. No luck. I am quite sure the mangoes I saw from Mexico and the pineapple from Brazil had been zapped in order to make it into this country.

The wholesalers and retailers of this country are letting us down. Their venue is the perfect place to educate the consumer on the benefits of and safety of irradiated food. Millions of food poisonings could be avoided, and thousands of lives saved. Food waste could be cut way down, as shelf life would be greatly extended just as pasteurization of milk extends its shelf life. And while I’m at it, wholesalers and retailers should be promoting the benefits of GMOs instead of capitalizing on the fears of the consumer by using non-GMO labels. Combining the benefits of irradiation and GMOs would go a long ways toward supplying the world with safe, plentiful food through the rest of this century.

Jack DeWitt is a farmer-agronomist with farming experience that spans the decades since the end of horse farming to the age of GPS and precision farming. He recounts all and predicts how we can have a future world with abundant food in his book “World Food Unlimited.” This article was republished from Agri-Times Northwest with permission.