California is by far the highest agriculture producing state in the United States, bringing in almost twice the cash receipts in 2020 than the second highest agriculture producing state, Iowa. The California Department of Food and Agriculture reports that over a third of U.S. vegetables and two thirds of U.S. fruit are produced in California.

California is a prospering state that has a significant impact on the food system across the U.S., but California has seen its agriculture output limited in recent years due to frequent drought conditions.

The National Integrated Drought Information System reports that California is often in a drought, and the droughts can last for years at a time. In response to them getting worse every year and the groundwater supply depleting, California officials passed a three-bill legislative package, the Sustainable Groundwater Management Act (SGMA).

SGMA was enacted in 2014 under Gov. Jerry Brown, with the goal of protecting groundwater for the long-term future. The three bipartisan bills that make up SGMA are separate and important distinctions within the act.

SB 1168 by state Sen. Fran Pavley instructs local agencies (Groundwater Sustainability Agencies) to create management plans, meaning that groundwater management should be tailored to the community. AB 1739 by Assemblyman Roger Dickinson says that, at a certain point, the state government (the California Department of Water Resources) can intervene if the local groups don’t sufficiently do their job. And SB 1319, also by Pavley, postpones the state’s action in certain places where surface water has been affected by groundwater pumping.

Brown was quoted in the LA Times shortly after SGMA came into play saying that by putting emphasis on local agencies he was “pushing the responsibility to where people really are.”

The overarching goal of SGMA is to have a plan to decrease groundwater usage on local levels rather than a statewide level. What all the local Groundwater Sustainability Agencies were tasked with doing was coming up with a plan by 2020 to cut groundwater draws to a sustainable level, and all the plans would be approved by the California Department of Water Resources by 2022. The DWR released a report in February 2022 addressing how many GSA plans were approved, and what the next steps are.

Although SGMA has bipartisan support, and seemingly everyone agrees that groundwater is a natural resource that cannot be exploited, Farm Bureau has shown concern that farmers could be negatively impacted by some SGMA actions, leading to detriments to the California economy as a whole as well.

Groundwater is being allocated by the GSA’s to landowners to reduce the amount drawn. Although everyone is suffering when they have to cut back on water draws, farmers are sometimes given no other choice but to yank out groves and let crops die in order for them to stay within their allocation. Everyone has to do their part to allow the basins to replenish themselves, but when agriculture suffers in California, all of California suffers. And now that the DWR has revised the plans, groundwater allotments are small fractions of what were allowed before.

To address this, groundwater trading was introduced. Since groundwater draws can be measured, if someone is drawing less than their allotted amount, they can sell the rest of their quota to someone else. This trading is monitored and regulated by GSAs.

Neither groundwater allocation nor groundwater trading is a perfect system, but hopefully these kinks get worked out before farmers feel that they have to pack up and leave California.

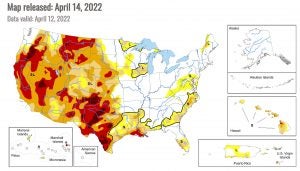

The drought and accompanying challenges are generally affecting farmers across the western half of the U.S. The U.S. Drought Monitor and the National Integrated Drought Information System show that from the High Plains and west, the country is between moderate and exceptional drought.

Other U.S. states have legislation similar to SGMA. Texas, for example, is governed by the Rule of Capture; Arizona, on the other hand, has one of the strictest systems. The Arizona Groundwater Management Act, which was put into effect in 1980, established that there can be no new irrigated agriculture land, and residential land sales cannot be made unless the seller can prove that there is at minimum a 100 year’s water supply.

The effects on agriculture from the current droughts are huge, and they will continue to become graver if water cannot be sustainably managed throughout a drought.

But the future of agriculture is not entirely bleak, science in agriculture has advanced further throughout time than we could have previously imagined. We now have more drought-resistant varieties of crops, technology to recycle water from wash systems and manure collection, and vertical farming, which uses far less water. Figuring out how to farm with the least amount of water possible is a challenge, but nothing has ever stopped farmers before!

Elizabeth Maslyn is a Cornell University student pursuing a career in the dairy industry. Her passion for agriculture has driven her desire to learn more, and let the voices of our farmers be heard.