Corn is king, as they say.

Literally, there’s a corn palace in South Dakota where tourists are entertained by wall murals bedazzled with kernels of different colors. You can book the facility for your nuptials, attend a theater production, and nibble on a “world famous” popcorn ball.

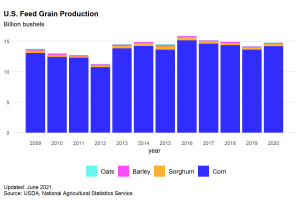

But designating corn as royalty is usually a reference to the crop’s status as an economic powerhouse. Until recently it was the number one crop grown in the United States. According to the U.S. Department of Agriculture, American farmers plant more than 90 million acres into corn. The U.S. is the world’s largest corn producer and exports between 10 and 20 percent of annual production.

American farmers have reached corn dominance by adopting and implementing the best of modern agriculture. Although the average amount of acres growing corn hasn’t dramatically shifted, the average yields across the country have risen dramatically. And it’s all thanks to improvements in technology and production practices.

So if things are so good, why is the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency playing games with a vital tool for corn growers?

The EPA is currently contemplating a drastically reduced new aquatic ecosystem concentration equivalent level of concern (or “CE-LOC”) for the herbicide atrazine. Given the limited options for effective and safe herbicides, the move would be incredibly disruptive to growers’ ability to use atrazine. It prompted the so-called Triazine Network — which includes members of the National Corn Growers Association, the National Grain Sorghum Producers Association, the Florida Fruit and Vegetable Association, among others — to write a letter asking EPA Administrator Michael Regan to reconsider. The EPA had already established safe parameters for atrazine’s use based on a solid foundation of peer-reviewed research as part of the registration review process. So the growers suggest that, at a minimum, the EPA submit the proposed change to an independent scientific advisory panel for review since they doubt the best available science supports the move.

Atrazine is a triazine herbicide used by American farmers to control broadleaf and grassy weeds. It’s largely used by corn growers, although it’s also used on a variety of other crops, like sugar cane, macadamia nuts, and ornamental plants, as well as on golf courses. It works by disrupting invasive weeds’ ability to properly photosynthesize, though it’s generally safe for humans.

As any farmer knows, weeds are a big deal and can drastically impact yields. Weeds grow faster than most food crops, and they monopolize resources in the field: sunlight, soil nutrients, water, and growing space. A study from Kansas State University found that uncontrolled weeds would result in economic losses totaling $43 billion annually in the U.S. and Canada. So managing weeds is an important factor in economic sustainability.

There’s also an environmental impact. Herbicides help farmers adopt conservation practices like no-till and cover crops. Without them, farmers are forced to hire labor to do it by hand or use routine tillage throughout the growing season to combat weeds, options that rely on labor, increase greenhouse gas emissions, and result in soil degradation. And higher yields supported by herbicides means the world doesn’t have to develop new farmland in places like the rainforest; we can grow all the crops we need on the land we already use.

By the way, consumers benefit from this too. In the U.S., shoppers save between $4.3 billion and $6.2 billion annually through lower prices for meat, eggs, dairy products, and ethanol thanks to atrazine and other herbicides.

Thanks to the COVID-19 pandemic and Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, we all recognize how sensitive our supply chains really are. Seemingly small changes in one sector can have massive consequences down the line.

The EPA’s decision on atrazine might seem like a small thing if it causes corn yields to dip. But we would see the ramifications from the availability of food to the cost of energy.

Amanda Zaluckyj blogs under the name The Farmer’s Daughter USA. Her goal is to promote farmers and tackle the misinformation swirling around the U.S. food industry.