This article was written by Risa Demasi, co-founder of Grassland Oregon, and is republished with permission as part of AGDAILY’s focus on cover crops.

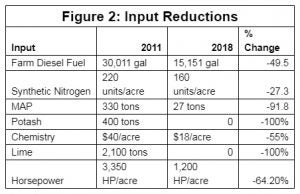

If you are a farmer who is thinking about trying cover crops this year, you are probably also wanting to see a change to your pocket book in addition to your soil’s health. For example, a 27.5 percent decrease in synthetic nitrogen, 49.5 percent decrease in farm diesel, 91.8 percent decrease in MAP (monoammonium phosphate), and a 100 percent decrease in both lime and potash applications — these are just a few of the impressive reductions to input costs Clark Land and Cattle have made from 2011 to 2018 — while improving yield averages year on year.

While visiting farms in the heart of the Corn Belt a few weeks ago, I had the privilege of paying a call to the 7,000-acre corn, soybean, and beef farm managed by Rick Clark in Williamsport, Indiana. Given the wet spring his area has had, I couldn’t help but notice the stark difference between his fields that we walked without the need for boots and his neighbor’s fields that were completely saturated. According to him, his field conditions are primarily down to the way the farm is managed.

Fifteen years ago, the farm transitioned to no-till soybeans. Five years later, it also transitioned corn into no-till and started planting cereal rye cover crops. However, it wasn’t until Mother Nature “shoved” the farm into what Clark calls “farming green” eight years ago that he started to maximize cover crop potential. In a nutshell, farming green is planting a cash crop into a living and growing cover crop, which is then terminated anywhere from three to 30 days after drilling the cash crop. A consistently wet planting season prevented the farm from terminating the cereal rye cover crop at the usual time that year, forcing them to plant into it. But rather than being the train wreck they all anticipated; it fundamentally changed the management of the farm.

Looking at the data

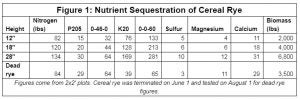

Clark is a firm believer in the power of data, recording as much as possible to make future management decisions. To fully understand what the cereal rye crop was contributing to the farming green system, a 2-by-2-foot sample was mowed down to the ground and overnighted to a lab for assessment on 12-inch, 18-inch, and 28-inch crop heights. Two months after termination, another sample was taken.

Looking at data in Figure 1, it became crystal clear to Clark that the longer he let his cover crop go, the more nutrients it sequestered. In his part of the world, getting cereal rye from 12 inches to 18 inches takes about four days in April — another reason to not be so quick to burn the cover crop to the ground at the end of March.

Tapping into the cover crop’s potential also proved to have significant financial gain by reducing input costs. From 2011 to 2018, the farm went from using 33,011 gallons of farm diesel to only 15,151 gallons (see Figure 2). With a good handle on the soil profile from annual testing, the farm was also able to eliminate the use of potash and lime.

While the figures show a drop from 220 units of nitrogen per acre to 160, Clark says this is quoted conservatively. To avoid a cover crop monoculture, the farm has transitioned away from cereal rye and started to use a cocktail mix of FIXatioN Balansa Clover, forage oats, winter peas, sorghum-sudangrass, tillage radish. FIXatioN Balansa Clover is an annual that can survive in temperatures as low as minus-14 degrees Fahrenheit and can produce more than 200 pounds of nitrogen per acre. In the fields with legume winter survival, Clark is only having to use 60 units of nitrogen per acre. The farm also prefers it to other clover species for its hollow stem, which makes it easy to terminate with a roller crimper.

Yield improvements

Aside from the serious reduction from input costs the farm has achieved, the other impressive part about the operation has been the consistent increase of yield for corn and soybean crops. Since 2011, corn has increased an average of 3.9 bushels per acre each year, and soybeans have increased 1.3 bushels per acre.

Clark says the cover crops have also reduced standard deviation for both cash crops. In 2011, soybeans had a standard deviation of 8.87 and corn had a standard deviation of 28.39. Since then, the standard deviation has declined to 2.75 for soybeans and 4.7 for corn — giving the farm more accurate yield predictions for marketing purposes. According to him, this leaves the farm in a position of strength and doesn’t leave him sitting up at night worrying.

A focus on soil health

So, how was this all achieved? A focus on soil health. Rather than chasing after yield and throwing everything and the kitchen sink at the cash crop, Clark made soil health the top priority. Then the rest followed.

While the farm will always be evolving, Clark offers a few pieces of advice to producers looking to maximize cover crop potential to reduce input costs: start slow with trial plots, data record everything, and, most importantly, don’t make it complicated.