I never imagined I would be a farmer. My relationship to food was simple: It came from a grocery store and my mom was a good cook.

In 1985, I moved to a home in the Bronx with a big backyard, and I decided to grow tomatoes. To my surprise, those tomatoes changed my understanding of food. The fruit was a vibrant red, grew on a fragrant vine and tasted incredible. I was hooked and sought out opportunities to learn more.

I started a community-run farmer’s market in 2004, La Familia Verde Farmer’s Market, which included five community gardens and four rural farmers. I felt proud to know that we were growing food for the community in our own community gardens. It was a triumph for the community, as well as the farmers and it continues to feed our community today.

Where are the Black farmers?

As the market flourished and as I dove deeper into agriculture courses and opportunities, I found myself wondering, “Where are the Black farmers?”

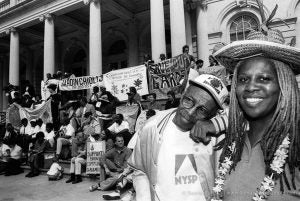

In 2010, I initiated the first Black Farmers and Urban Gardeners Conference. Over 500 people jammed the Boys and Girls High School in New York City to discuss, “What is for dinner?”

Prior to 2010, farming conferences were predominately White centered, making no reference or contributions from Black people. Now for the first time, we had a conference with our faces, discussing our issues and providing solutions from a Black perspective. Prior to COVID-19, the conferences were an opportunity for Black people to educate and network themselves around food, land, and resources. Sidelined by the pandemic the past two years, I am hopeful that these conferences will resume in 2022.

Food & agriculture’s unsavory history

Growing food caused me to examine larger issues connected to food. I’ve come to realize that the agriculture sector beyond my backyard is complicated. Today’s food system is rife with injustices, spurred by economic and wealth disparity, racism, poverty, and hunger.

I saw hunger and poverty in a country with so much wealth. I saw the blatant divisions between the fresh, healthy, local food found in White, affluent neighborhoods compared to the processed, unhealthy food available in poor communities of color.

The injustices plaguing the food system extend beyond hunger and poverty. Historically, the wealth of the United States was built on the backs of indigenous and enslaved people — yet these communities have never prospered from it. According to recent data, the median White household holds $188,200 in wealth, compared to the median Black household holding only $24,000 in wealth. White farmers own 98 percent of farmland, and Black farmers own less than two percent. The disparities and injustices of the past resulted in today’s inequitable, bias two-tier food system.

Food deserts vs. food apartheid

In the early 2000, the food and agriculture community began discussing “food deserts.” My community was labeled as such, and I recall thinking, “What are they talking about? We have plenty of processed junk food.” The technical term, food desert, is a comfortable way for those outside poor communities to discuss the limited access to affordable, nutritious foods in these communities. This term avoids the difficult topics of economics, race, history, and where you live, and how these factors impact food options and overall health.

I prefer the term “food apartheid,” segregation on the grounds of nutritious food access. This term is uncomfortable; however, if we want to move forward, we must settle into this discomfort and acknowledge the truth: The United States is divided along race and economic status and this division severely impacts food access and health.

Additionally, we must change how we view the poor and the sick — and recognize that many people are sick because they are poor and have not had the same access to healthy foods.

Making the powerless powerful

Empowering communities can address food apartheid. Outside groups and resources are part of the solution, but they need to stop asking what communities need, which puts the community at a deficit and makes them dependent on the outside support. Rather these groups should focus on what the communities want, which empowers the community to act in their own interest. Community leaders need opportunities for self-sufficiency and the ability to be part processes that influences their community.

We must make powerless community powerful. This transition requires the community to have opportunities, tools, resources, and capital necessary to climb out of poverty. From my experience, investments in entrepreneurship, financial literacy, social capital, and opportunities to foster communal wealth are most effective in righting historically unjust the power dynamics. As example, we recently established a Black Farmer Fund to help Black farm and businesses in New York State with capital. What makes the fund so unique is the decision-making process comes from the community for the community. Start up capital is given to the businesses along with financial education to help businesses to succeed.

Another impactful way to create change is for White advocates and farmers to stand up for Black and minority communities and farmers. White and affluent communities must be vocal about the injustices they see and help support solutions identified by the Black and minority communities.

We cannot accept a food system that discriminates against those who are fighting to gain parity, access to land and sovereignty, namely people of color. Alas, my work speaking out on these difficult topics continues until we have a food system that is fair, just and equitable for all.

Karen Washington, co-owner of Rise and Root Farm, is a farmer, activist, and food advocate. Growing up in New York City, she has spent decades promoting urban farming to ensure all residents have access to affordable, nutritious foods. As a member of La Familia Verde Community Garden Coalition, she helped launch city farmers market which provides fresh produce to her community. She also co-founded the Black Urban Growers organization that provides networking and support for Black growers. Washington continues to advocate for food justice and grows organic foods at Rise and Root Farm.

This article was originally published by Foundation for Food & Agriculture Research and is republished here with permission on behalf of American Farmland Trust.