We know the FFA Creed, we recognize the blue corduroy, and we appreciate the fond memories — but do we know FFA’s deep all-American roots? The program has become a hallmark of agricultural ingenuity and leadership, recognized by the agriculture and urban worlds alike. As with any cultural mainstay, it’s easy to forget there’s a real story behind the scenes with flesh and blood people.

Born and nurtured in the heart of Virginia, what began as a simple program for farm boys would become a national icon thanks to four men with a fervor for agriculture and education.

Founding fathers

The story begins with a man named Henry Groseclose, a teacher from Buckingham County, Virginia. He is often considered the organizer of the program, says John Hillison, a retired agriculture education professor at Virginia Tech and a fount of FFA history.

Together with Edmund Magill, an itinerant teacher trainer who worked with agricultural education teachers throughout Virginia; Harry Sanders, an ag teacher from Manassas High School; and Walter Newman, who would be named as the head state supervisor of agricultural education for the Virginia Department of Education; Groseclose organized the Future Farmers of Virginia (FFV), which would oneday become the National FFA Organization.

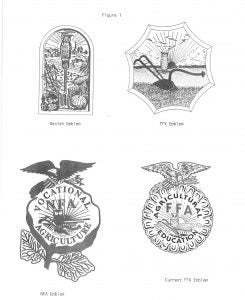

“Groseclose did many important things for the FFV,” Hillison said. “He wrote the FFV Constitution, created progressive levels of membership, established opening ceremonies, and designed its emblem.”

Groseclose also named the organization, which is partly based on the original meaning of First Families of Virginia. These pieces would eventually be models for the National FFA, where he also served as the first secretary-treasurer.

In September 1925, the four men gathered at the Virginia Tech Agricultural Education Department to visit with faculty. At a solid oak table, they discussed their vision of the framework for the FFV. Today that table bears a plaque with their names in commemoration of the event.

Here’s a little-known fun fact — this historic meeting was witnessed by a young ag teacher from Rural Retreat High School named Jim Hoge.

“During the meeting, Hoge was able to witness a monumental event. He heard Walter Newman share something he had learned while in the Virginia Department of Education,” Hillison explained. “Newman had come to realize the farm boys did not have as much confidence in themselves as their city cousins.”

The solution he offered to help give the farm boys more confidence was a formal organization. One that he hoped would provide experiences and leadership opportunities.

A few years later that vision made it to the national level.

In 1928, 33 ag students from 18 states, many of which were members of the newly minted “Future Farmer” groups, gathered at a meeting during the American Royal Livestock Show in Kansas City. At the Baltimore Hotel they formed National FFA — just one year later at the same location the first national convention was held.

Rooted in agriculture

The agricultural backgrounds of the founders ranged anywhere from horticulture to animal science; perhaps the common denominator was their passion for teaching youth. Every one of the FFV founders had a passion to help youth by becoming teachers.

Hillison had the privilege of being a personal acquaintance of Harry Sanders. He recalls many of the lesser-known ways in which Sanders continually gave to Virginia Tech students and the FFV/FFA programs.

“The school’s department of education’s first scholarship was named after him. Both Sanders and his wife helped present the scholarship to recipients at the program’s spring banquets,” he recalled. “Sanders had a basement apartment where students majoring in agricultural education could live for low rent and wise counsel. He also played a key role in starting a student loan program for majors who had an emergency need for money.”

FFA today

The idea for FFV and eventually the National FFA Organization were certainly unique ones at the time. While there was an abundance of “commodity clubs” throughout Virginia that narrowed in on specific ag-related disciplines, the founders took a unique risk in creating a more general organization.

“If specific commodity clubs had been retained, it is doubtful that anyone would have become national and had the impact or influence that the FFA has had,” Hillison said. “Fortunately, the decision was made at the right time when the FFV founders and others were ready to make a change by taking a risk.”

Undoubtedly the FFA, as it is today, surpasses what the original founders could have imagined — we’re talking a national membership of over 760,000 and 65,000 convention attendees. The breath of its history is long, but there are key highlights through those first few decades.

The desegregation of schools that allowed for the African-American-centric New Farmers of America (NFA) to merge with the National FFA Organization in 1965, Hillison said, was a notable milestone along the journey to a stronger organization.

Just a few years later, in 1969, girls were also admitted into the program, which further enhanced leadership, including officer teams along with both career and leadership development events.

The 1917 Smith-Hughes Act — which greatly influenced the roots of FFV — gave a narrow definition to agriculture exclusively meaning farming.

“When the term agriculture was more broadly defined by federal legislation in the 1960s,” Hillison said, “the FFA quickly changed with it.”

That’s shown through immensely as the organization now encompasses agribusiness business, farming, and the many other allied industries of which FFA has produced leaders for.

“The original purpose of the FFV was to give its members who were farm children more confidence in themselves,” Hillison reflected. “Today success can be measured by observing the activities conducted by individual members, chapter, state and national FFA events. Some of the most impressive meetings ever held have occurred at FFA events run by adolescent members with great confidence.”

Jaclyn Krymowski is a graduate of The Ohio State University with a major in animal industries and minor in agriculture communications. She is an enthusiastic “agvocate,” professional freelance writer, and blogs at the-herdbook.com.