For obvious reasons, the most physically demanding jobs — roofers, pile drivers, fishermen, lumberjacks, take your pick of many others — are primarily filled by people no older than 40. But farming, a mixture of hard work and long hours, even as technology automates some tasks, is a dramatic outlier. The extreme demographic skew towards older farmers is a global phenomenon, decades in the making. And in its wake is a worsening crisis reflected by one question: where will the talent come from to manage the fields in the future?

The numbers paint a troubling picture. According to global agricultural experts, the average age of farmers globally is about 60, even in regions like Africa and the Philippines where the median age of the population is just over 20. And this trend is not new. In the U.S., the average age of farm operators was 50 in 1978, 57 in 2007 and 59 in 2017 when the USDA conducted its last census.

Some of the blame for this trend can be laid on the perception that agriculture careers and rural life may not give young people opportunities like the city. And in many cases, this perception comes from elders who encourage their children to explore the possibilities urban life may bring.

“I have yet to have a rice farmer tell me that they want their children to grow up to be rice farmers,” said Robert Ziegler, former director general of the International Rice Institute, at a World Economic Forum meeting.

And as urbanization explodes — nearly 70 percent of people will live in cities by 2050 — the notion that agricultural activities can be fulfilling has waned, along with basic common sense about where our food comes from. (One UK farm expert tells a story of a British school teacher on a field trip to a farm. The teacher asked the farmer not to milk the cows because the students would be terrified by the blood from killing the animal).

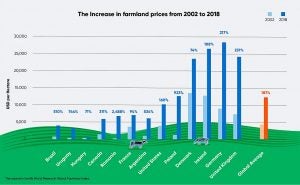

Economics are also a deterrent for young people. The financial barriers to entry for owning or running a farm, particularly in developed regions, have risen significantly. As agricultural technology and input gains advanced rapidly throughout the 20th century and into the 21st century — from tractors and tillers to drones, sensors, and seed genetics — yields improved, increasing the dollar returns from a single field. For instance, U.S. corn yields increased from fewer than 60 bushels per acre in 1960 to about 164 bpa in 2016. The value of farmland has also skyrocketed. Taking a recent snapshot, the Global Farmland Index of land prices in 15 global agricultural markets grew by an average annualized rate of 14.8 percent between 2002 and 2016. Taking a longer view, in 1900 the average value of a hectare of farmland in the U.S. was about $1,300, adjusted for inflation. By 2018, that figure had jumped to $10,205.

The combination of expensive mechanized, high-tech equipment and the cost of agricultural land has driven initial startup costs for new farmers to prohibitive levels. It has also greatly extended the time it takes for a return on investment. According to a survey from the National Young Farmers Coalition of more than 3,500 new young farmers in the US, finding and affording productive acreage was the primary impediment in the way of an agriculture career. “We have a lot of older farmers who are over-capitalized and looking to retire and a lot of younger farmers under-capitalized with no land,” Eric Skokan, co-owner of Boulder County (Colorado) Black Cat Farm, told a local newspaper.

To help overcome this impediment, the U.S. Department of Agriculture has a number of loan programs that, in part, are geared to new farmers, seeking to make farming demographics younger and more diverse. In addition, the European Union has a series of agricultural support campaigns earmarked for youth. Localities in the US are also addressing this issue. Both Colorado and Minnesota have recently passed first-in-the-U.S. laws that provide a tax deduction for farmers that sell or rent their land or other agricultural assets to new farmers.

Mindful of the impact that this demographic dilemma could have on global food supplies in the future, policymakers and NGOs are taking steps to alleviate it. In Africa, organizations like Youth Empowerment in Sustainable Agriculture, Young Professionals for Agricultural Development and Ayihalo are training thousands of potential young farmers in modern planting, crop health, and financing methods for managing a farm. They also serve as youth in agriculture career advocacy programs. Similar efforts in the US and UK include the National Young Farmers Coalition and the National Federation of Young Farmers Clubs, respectively.

Perhaps the best sign that these skewed farming demographics may improve to some small degree over time, is the enthusiasm of the relatively small group of younger people willing to give agriculture a chance. Andrew Barsness, who runs a farm in Hoffman, Minnesota, wrote a blog post on the National Young Farmers Coalition site. In it, he described taking over his grandfather’s 280-acre grain farm as an unexpected turn in his life. “Before the spring of 2011, the idea of becoming a farmer was completely foreign to me,” Barsness said. “Now I know that there is nothing that I would rather do for a living. Hardships are inherent in farming. For me however, the freedom, variety, and entrepreneurship that farming offers make it as rewarding as it is addictive.”

Still, comments like those notwithstanding, it’s impossible to say whether large groups of young people will ever be convinced that farming is a trade worth considering. But after a recent survey found that two-thirds of US agricultural acreage will need a new farmer over the next 50 years, it seems clear the situation will be untenable if young people don’t.