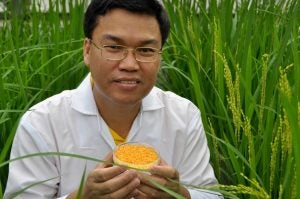

Golden rice may finally have its day. With a recent ruling in the Philippines that Golden rice is safe for consumption, the island nation could become the first Asian country to approve it for planting. Bangladesh, too, has recently made some positive moves toward the crop.

It has been nearly 20 years since Golden rice was a Time cover story with the caption, “This Rice Could Save a Million Kids a Year.” Almost immediately, Greenpeace declared war on Golden rice because it was genetically engineered to produce beta carotene — the precursor of vitamin A — in the rice kernel. On Feb. 12, 2001, Golden rice was again the subject of a Time cover — “This Rice Could Save a Million Kids a Year, but protesters believe such genetically modified foods are bad for us and our planet. Is the rice worth the risk?”

There are thousands of rice varieties in the world, and they are a staple for nearly half of the world’s people. But the very poor who depend on rice for nearly 100 percent of their calories can suffer from vitamin A deficiency, a nutritionally acquired immune deficiency syndrome. Especially children and pregnant women. Estimates vary, but some sources show a million people, mostly children, die a slow death each year because of this deficiency. An additional 250,000 to 500,000 children become permanently blind.

Rice produces beta carotene in all parts of the plant except the endosperm of the kernel (the bran contains beta carotene, but it is removed before cooking). If the plant’s kernels could produce beta carotene — the compound that turns corn kernels and daffodils yellow — digestive enzymes of rice eaters could make vitamin A and save an estimated million lives per year and prevent permanent blindness in several hundred thousand more.

In 1984 a group of rice breeders gathered at the International Rice Institute (IRRI) near Manila, Philippines, to discuss future rice improvements. Among them was Peter Jennings, the IRRI breeder who had bred the “miracle rice” variety IR8 that, along with Norman Borlaug’s “miracle” wheat varieties, produced the Green Revolution that saved millions of lives in India and other countries in South Asia in the 1970s forward. His suggestion for the next “miracle” was to develop a variety with yellow endosperm. It was the beginning of a 15-year, multi-million dollar investment by the Rockefeller Foundation. (See Golden Rice, the Imperiled Birth of a GMO Superfood by Ed Regis). Later the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation would put in millions of dollars more.

By 1999, researchers working in a greenhouse in Zurich, Switzerland, had succeeded in transferring a gene called PSY from daffodil and one called CRIT from a soil bacterium into a rice plant that then produced seeds with yellow endosperm. (This was not just any old ordinary greenhouse. It had 3-inch armored glass to prevent violent anti-GMO attacks, and airlocks to prevent any of their “dangerous” genes from escaping. Switzerland is among the most anti-GMO countries in the world.) All that was needed was to transfer the genes to locally adapted varieties, a feat that could be accomplished in a few years with conventional breeding methods.

Well, not quite all. For one thing, the amount of beta carotene in the kernels was low — 1.6 micrograms per gram. Another problem was related to patents. The inventors, Ingo Potrykus and Peter Beyer, had used patented techniques in their research, and now needed to obtain licenses or permission from those patent holders before commercialization. Monsanto was one of the patent holders, and they gave permission — no charge. This was a humanitarian project. But another complication was that some of their funding had come from the European Commission’s Community Biotech program, which stipulated that a European commercial firm must be a partner in the research and have commercialization rights to any resulting products. Zeneca, a British agribusiness company, agreed to be that partner. In a transactional agreement, the humanitarian project retained rights to use the technology to assist the resource poor, including small-scale farmers, defined as being farmers with no more than $10,000 in annual sales. Zeneca reserved the right to make commercial sales to farmers.

Then Zeneca was purchased by Syngenta, but the humanitarian rights were retained by the research group. Syngenta added a PSY gene from corn plus some gene promoters and by 2005 came up with a variety that produced up to 31 micrograms of beta carotene per gram in the kernel. One ounce (28.35g) of this rice would provide the daily Vitamin A requirement for an 8-year-old child. Three ounces per day would meet the requirements for an adult. Small farmers across the developing world could grow it, save some seed for the next crop, and never have to worry their children would go blind because of prior nutritional deficiencies.

But by this time, Greenpeace’s anti-Golden rice campaign had been going for five years and had succeeded in convincing governments in Asia and Africa that the technology was dangerous to people and the environment. As a result, since 2005, an estimated 14 million children have died of Vitamin A deficiency and an estimated 3.5 million to 7 million are permanently blind. In December 2017, Mitch Daniels, President of Purdue University, wrote an Op-Ed for the Washington Post titled, “Avoiding GMOs isn’t just anti-science. It’s immoral.” He writes, “This is the kind of foolishness that rich societies can afford to indulge. But when they attempt to inflict their superstitions on the poor and hungry peoples of the planet, the cost shifts from affordable to dangerous and the debate from scientific to moral.”

In June 2016, a letter from 107 Nobel Laureates (since grown to 151 signees) read at a news conference claimed Greenpeace has “misrepresented (GMOs) risks, benefits, and impacts, and supported the criminal destruction of approved field trials and research projects. … How many poor people in the world must die before we consider this a ‘crime against humanity’?” Good question. I hope people who contribute to Greenpeace and other anti-GMO NGOs will give it some thought.

One final note. On Oct. 16, 2004, Syngenta announced it was giving up all rights to commercialization of Golden rice, and donating them to The Golden Rice Humanitarian Board. They would continue, however, to honor the legal agreement they had entered into with Golden Rice’s creators to support their endeavor. This statement by a big corporation was met with a cynical retort from Greenpeace: “Syngenta claims to be trying to help people suffering from vitamin deficiency … [but it is] clear that the GE industry uses ‘Golden’ rice to campaign for an easier marketing of GE seeds. It looks like the industry is campaigning for their GE seeds while abusing people that suffer from malnutrition.”

In his book, Ed Regis rebuts: “Abusing people? None of this wild rhetoric (promulgated by Greenpeace) [is] even remotely true or [makes] any sense…” The real abuse is that Greenpeace’s 20-year campaign to convince African and Asian governments that any GMO is dangerous to their people and the environment is denying millions of people life-saving nutrition.

Jack DeWitt is a farmer-agronomist with farming experience that spans the decades since the end of horse farming to the age of GPS and precision farming. He recounts all and predicts how we can have a future world with abundant food in his book “World Food Unlimited.” A version of this article was republished from Agri-Times Northwest with permission.

Ryan Tipps contributed reporting to this article.