As I was scrolling through Facebook the other day, I ran across a story that seems to get recycled year after year: a fast food burger and fries that someone has had sitting around for years, and miraculously, hasn’t spoiled. The explanation that follows is never one of reasoning and science, but one of fear and outrage. The blame is usually placed on the preservatives or that it’s “fake food” or that it’s so unhealthy that it doesn’t spoil.

The list goes on and on, but these claims are long on false assumptions and short on science. You see, the explanation is quite simple, and it’s based on one of the earliest known methods of food preservation, which is known as dehydration. Sun-drying, air-drying, and smoking, which preserve food by removing water, were some of the first dehydration techniques ever used.

Here’s the image of the fast food meal and caption that I shared on Facebook to correct the misinformation that’s been swirling around recently:

A local news station posted this a few days ago, and the comments…oh, the comments. Life is so much less scary when you understand basic scientific concepts. So, let’s talk about water activity. When developing a shelf stable product, water activity is the most important factor to control in order to make sure the product doesn’t mold or grow harmful bacteria. Basically, under a certain threshold, there’s not enough moisture to support mold or bacterial growth.

So, what happens to a burger and fries when it sits out in the open in a non-humid environment? It dries out, the water activity decreases and mold and bacteria can’t grow. Essentially, you end up with some beef jerky, two large croutons and potato chips. Have you ever worried about opening a bag of potato chips and seeing mold? No, because, science.

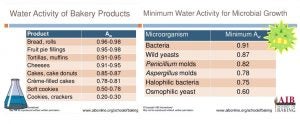

So, what exactly is water activity? It’s not just a fancy term for moisture. Moisture, or water content, is a measure of the total amount of water contained in a food and is typically expressed as a percent of the total weight. Water Activity (aw), on the other hand, is a measure of the “free” or “unbound” water that is available to react and to be utilized by microorganisms. It’s measured on a scale from 0 to 1, where one indicates pure water and zero indicates the total absence of “free” water molecules. Different foods have different water activities and different microorganisms require differing minimum water activities to survive, as shown in the tables below. Higher aw substances tend to support more microorganisms. Below an aw of 0.6, no bacteria, mold or yeast can grow.

Moisture migrates from areas of high aw to areas of low aw until equilibrium is established. So, if we go back to the burger and fries example above, if the aw of the food is greater than that of the surrounding air, the moisture will migrate from the food to the air, thereby decreasing the aw of the food. If the equilibrium aw is lower than what is required for mold and bacterial growth and is reached before any microorganisms have had a chance to grow, then mold and bacteria simply won’t be present on the resulting dried out food.

Drying, or dehydration, has been used to preserve foods such as fruit, meat, and bread for thousands of years, yet for some reason people continue to get freaked out when it happens to a fast food meal, but have no issues with eating raisins, beef jerky, or croutons. That’s not to say that the 10-year-old fast food meal is OK to eat. It most certainly is not. There are other indicators of food spoilage, such as the oxidation of fats, which results in rancidity. So, just because there may not be visual indicators, such as mold, it certainly doesn’t mean that the food hasn’t gone bad.

The argument still arises that it must be the preservatives or some scary chemicals in the fast food meal that allow this to happen, and that it could never happen with a home cooked burger, but that’s not true either. Preservatives can help to inhibit mold growth, but only for so long. They can be used to extend shelf life for days or weeks, but not for 10 years like this burger and fries. Due to the high fat content of the fries, they could have already been at a low enough aw after the frying process, but again, the fat has certainly oxidized despite there being no apparent visual indication of spoilage. Both the burger and the bun likely have aw values above 0.6 initially, so in order to inhibit mold and bacterial growth for that amount of time, you’d need reduce the aw, adjust the pH, starve it of oxygen, and/or decrease the temperature to a level that doesn’t allow for microorganisms to live. This is what is referred to as FAT TOM in the food industry, which stands for food, acidity (pH), time, temperature, oxygen, and moisture. FAT TOM is a mnemonic device to help remember the six factors that contribute to food spoilage. In this case, the aw of the food was decreased sufficiently due to sitting out in a non-humid environment.

Someone actually did an experiment to see if the same thing would happen with a home cooked 100 percent ground beef burger of the same diameter and thickness as a McDonald’s burger, and it turns out that the same thing happened with both burgers that were stored in the same conditions. Both burgers dried out, aw decreased, and there was no mold or bacterial growth. In addition, both the fast food and home cooked burgers that were kept in sealed plastic bags ended up with mold growth because the equilibrium aw ends up being greater due to moisture being trapped inside the bag.

So, is there something sinister going on with the immortal fast food meal? Should we be afraid of the fact that it can sit out for years at room temperature without growing mold or showing any visual signs of spoilage? Should we base nutritional value off of how long a food item can survive without mold growth after it dries out? Of course not. We aren’t afraid of dried fruits or the lone cracker that fell out of the package and has been hiding in the pantry for years. We aren’t afraid of the box of lasagna noodles that expired three years ago or the open box of cereal that nobody finished and, upon trying it some time later, realized it got stale, but not moldy. We typically don’t assess the nutritional value of any other foods based upon how long they last in our pantry.

I’m all for teaching healthy eating habits, but using pseudoscience as a means to create fear around specific foods really isn’t benefiting anyone.

Food Science Babe is the pseudonym of an agvocate and writer who focuses specifically on the science behind our food. She has a degree in chemical engineering and has worked in the food industry for more than decade, both in the conventional and in the natural/organic sectors.