When everything is reported to cause cancer by some loose standard, how do we recognize actual threats that can induce a serious disease?

It is fall in Florida, which means the brutal summer heat is almost over and we can plant the damn garden. Over my life I’ve found great solace in growing my own food, and in north-central Florida you get two seasons to do it — fall and spring, two seasons separated by a freeze event or two that represents our little microwinter.

This year the garden is expanded to epic proportions and features a lot of climbing vegetables. Others, like tomatoes, grow better if tethered rather than using the flimsy tomato cages from home improvement stores.

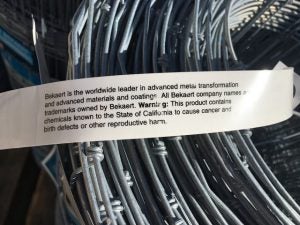

This year I actually sprung for some new fencing — but the warning tag had me concerned.

What? My fence contains chemicals? Technically metal is a chemical, so they have it right there. The warning must be referring to some component in the alloy that was shown somewhere to affect cells in a dish, or some other circuitous connection to human disease.

I just don’t understand where the risk is. If it is fencing in my home, my veggies or my dog … will I get cancer? Will I develop birth defects a half century after I was born? Will the fence imperil future generations?

When we hear about coffee, pumpkin puree and tiffany lamps causing cancer in California, it frames an important issue. Regulators don’t understand risk or public health.

The consequence? A society of individuals freaked out about their morning joe, the safe stuff the farmer sprays, or the fence around their house.

And imagine if someone fences their property on the border of California and Nevada. They’d be wise to do their major sitting time on the Nevada side, just be to safe. Over in Cali you’re literally surrounded by a carcinogen.

This silly tale frames a current debate. Why are non-scientists defining risk — especially when they deceive the public by not telling the truth about risk? It is the ultimate cry wolf. When everything is reported to cause health problems it makes us less able to recognize actual threats, which ultimately is a much greater risk to human health.

Kevin Folta is a land-grant scientist exploring ways to make better food with less input, and how to communicate science. This article was published with his permission. All of Dr. Folta’s funding can be found at kevinfolta.com/transparency.