Whole milk powder manufactured in New Zealand in 1907, then transported to the South Pole in Antarctica, was discovered more than a century later.

The findings have allowed dairy researchers to answer the question: Is the milk we enjoy today different from the milk consumed in previous generations?

A new comparative study in the Journal of Dairy Science, published by the American Dairy Science Association and Elsevier, has peered back in time to demonstrate that — despite advancements in selective breeding and changes to farm practices — milk of the past and milk today share more similarities than differences and are still crucial building blocks of human nutrition.

On New Year’s Day in 1908, explorer Ernest Shackleton’s British Antarctic Expedition aboard the ship Nimrod set sail from Lyttelton, New Zealand, on a quest to be the first to set foot on the South Pole.

While the wharf was packed with well-wishers, the ship was packed with dairy: 1,000 pounds of dried whole milk powder, 192 pounds of butter, and two cases of cheese. Shackleton and his crew would make it farther south than anyone before them — within 100 nautical miles of the Pole — and leave behind their base camp.

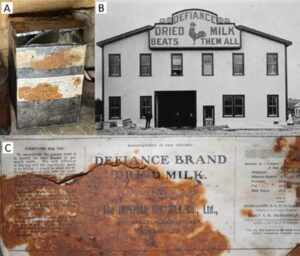

A century later, one remaining container of Defiance brand whole milk powder was discovered during the Antarctic Heritage Trust restoration project, having been frozen at Shackelton’s base camp for the past 100 years.

Lead investigator Skelte G. Anema, principal research scientist with Fonterra Research and Development Centre in Palmerston North, New Zealand, explained the discovery’s significance.

“The Shackleton dried milk is possibly the best-preserved sample manufactured during the pioneering years of commercial milk powder production, and its discovery gives us a once-in-a-lifetime chance to understand the similarities and differences between a roller-dried milk powder manufactured over 100 years ago with modern spray-dried counterparts,” Anema said. “Before we had vacuum-assisted evaporation, milk powders in the early twentieth century were manufactured by a roller-drying process involving boiling-hot milk being poured between two steam-heated revolving cylinders so that the water evaporated, leaving a thin sheet of dried milk that would have been milled and sieved.”

We know these early milk powders weren’t as sophisticated as they are today, but what other differences existed?

With the help of the Antarctic Heritage Trust, Anema and an interdisciplinary team of scientists with the Fonterra Research and Development Centre were able to study a few hundred grams of Defiance milk. They compared it with two modern-day commercial, noninstantized spray-dried whole milk powder samples from Fonterra.

Their analysis involved comparing the major component composition, major and trace mineral composition, protein composition, fatty acid composition, phospholipid composition microstructural properties, color analysis, and volatile component analysis of the different whole milk powder samples.

The results proved surprising and contrary to claims of changes in milk over time.

Anema elaborated, “Despite more than a century between the samples, the composition of bulk components and detailed protein, fat, and minor components have not changed drastically in the intervening years.”

The fatty acid composition, phospholipid composition, and protein composition, including casein and whey protein genetic variations, were remarkably similar overall.

The major mineral components were also alike between samples, except for high levels of lead, tin, iron, and other trace minerals found in the Shackleton whole milk powder — likely from the tin-plated can it was stored in and the equipment and water supply of the day.

Anema clarified, “These issues have been essentially eliminated from modern milk powders through the use of stainless steel and quality water services.”

Another notable difference was the presence of oxidation-related volatile aroma compounds in the Shackleton samples.

Anema said, “Perhaps from less-than-ideal collection and storage of the raw milk before drying, but it’s much more likely that — even in frozen conditions — being stored in an open tin for a century is going to result in continued oxidation.”

Despite the remarkable similarities, the team was eager to point out that the modern spray-dried whole milk powders were substantially superior in terms of the powder quality — particularly regarding appearance and their ability to be easily dissolved in water.

Overall, this Antarctic time capsule provides a rare and important glimpse into the evolution of dairy food production. It highlights the improvements the dairy sector has made and its enduring influence.

Anema noted, “The Shackleton samples are a testament to the importance of dairy products, which are rich in protein and energy as well as flexible enough to be powdered for easy transport, preparation, and consumption.”

Whether at the turn of the twentieth century or today, these results underscore that dairy products serve as an essential foundation for human nutrition — fueling our discoveries past and present.