A recent article by The Washington Post titled, Look for these 9 red flags to identify food that is ultra-processed, is a trite rehash of many food misconceptions that have swirled on social media for years, peddled by the likes of pseudo-celebrities under the monikers of Food Babe and FlavCity. It comes across as nutrient-deficient reporting, ignorant of science and steeped in “shock-value” writing.

Even worse, we didn’t come across this article during a passive search of The Post‘s website; no, this article was aggressively promoted by the publication through an app alert, helping to ensure it would have maximum reach and impact.

And this is problematic not solely because of the questionable content in the article.

Because Washington Post owner Jeff Bezos also owns Whole Foods, the grocery chain that “sells products free from hydrogenated fats and artificial colors, flavors, and preservatives,” the newspaper has a clear stake in the kind of food messaging that is distributed across the mainstream. In fact, The Post has taken criticism in years past for its food and farm reporting, specifically its pessimism about the dairy industry, as well as being on the receiving end of a hard-hitting rebuttal from the U.S. Department of Agriculture over false and misleading reporting.

The most recent headline teases The Post‘s piece as zeroing in on ultra-processed foods, which is definitely something to be addressed in today’s society. However, it’s the meat of the article that sees it go off the rails. The article — written by health columnist self-proclaimed “wellness junkie” Anahad O’Connor — embraces broad food stereotypes about products with “more than three ingredients,” and “added sugars and sweeteners,” and “instant and flavored varieties.”

In all, here are the nine categories The Post castigates:

- More than three ingredients

- Thickeners, stabilizers, or emulsifiers

- Added sugars and sweeteners

- Ingredients that end in ‘-ose’

- Artificial or ‘fake’ sugars

- Health claims

- Low-sugar promises

- Instant and flavored varieties

- Could you make it in your kitchen

Perhaps the highlight (or, would it be “lowlight”?) of embellishment listed in The Washington Post article was the arbitrary claim that the best foods have no more than three ingredients. Of the more than 2,500 user comments on the article, this one was the most highly criticized. The author referenced bread in the article, encouraging shoppers to “choose a brand that contains only simple ingredients, such as wheat flour, barley flour, sourdough starter, salt, nuts, or raisins.”

One comment stated, “Three-ingredient bread? Good luck with that. First of all, the flour that bakers use is enriched, which already puts you up to seven or eight ingredients. These are not bad things, they are things like iron, that the body needs. And you need yeast. And you need salt.”

One independent food science expert rebuts The Post‘s point as well, saying, “There’s no scientific basis to this rule and certainly no need to continue perpetuating it. Leave it behind, and for your tastebuds’ sake — season your food!”

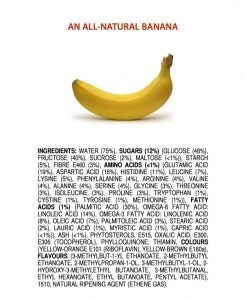

The Washington Post should see everything we put into our homemade lasagna, pot roast, or tzatziki dip. And really, are you going to cut out bananas because this Post article tells you to? Please don’t, despite this fruit exceeding the threshold of ingredients (and, gah, some of them are even hard to pronounce!).

The Washington Post soldiers onward by quoting a book author about artificial/”fake” sugars, specifically noting aspartame and sucralose. “Sugar and sweeteners often are added ‘to mask the off-putting taste from the preservatives and other ingredients that are added in,'” the article said.

However, there is an uncomfortable and derogatory inference being made here. Aspartame is one of the most extensively studied ingredients in our food supply, with more than 200 studies supporting its safety. Leading global health authorities such as the European Food Safety Authority and the FAO/WHO Joint Expert Committee on Food Additives conduct scientific risk assessments and safety evaluations of food additives. They have concluded that aspartame is safe for its intended uses. In the United States, the Food and Drug Administration’s recommendation of acceptable intake is 50 milligrams per kilogram of body weight (mg/kg) per day.

Likewise, sucralose is safe, with about 85 percent of consumed sucralose not being absorbed. Of the about 15 percent absorbed, none is broken down for energy, so sucralose does not provide any calories. All absorbed sucralose is excreted quickly in the urine.

Sounds a lot less scary when you understand the science, doesn’t it?

Now, there are valid reasons for avoiding certain ingredients, including allergies and sensitivities or just simply not preferring the taste or texture, so we’re certainly not saying you have to gorge yourself on everything The Post says here is bad. We love using whole ingredients in our cooking, and as is sensible, we advocate for diverse enjoyment of foods in moderation and following recommended scientific guidelines. Cutting out something that isn’t automatically good, either. Non-caloric sweeteners, for example, can colossally backfire, especially with diet sodas. The body, tricked into expecting actual sugar for “fuel,” feels jilted — triggering hunger centers — tempting you to simply eat food to make up the perceived deficit.

What is frustrating is the scope with which The Washington Post casts its reprimand. One user comment recognized correctly: “Yet another article attempting to define what is just bad terminology for describing food, with the usual asperation case on whole classes of foodstuffs (like breakfast cereals and yogurts) despite the fact that there is massive variation in what these products are made from and how they are produced.”

Nicely said.

Ironically, the biggest “red flag” in The Post’s article isn’t about the food it references but rather how the piece aligns so neatly with Whole Foods’ business model.