Colorado is racing to meet the year-end deadline to reintroduce gray wolves — a species eradicated from the state in the 1940s through a government-sponsored campaign.

Under the new law, wildlife officials will begin reintroduction efforts this month in northwest Colorado.

In 2020, voters passed Proposition 114 by a narrow 50.9 percent margin, which mandated that Colorado Parks and Wildlife develop a plan to start reintroducing gray wolves to the western part of the state by 2023. Only 13 of the state’s 64 counties voted in favor of the reintroduction.

Colorado’s wolf reintroduction plan was finalized in May of this year. It included the release of 10 to 15 wolves each year for at least five years, with the eventual goal of creating self-sustaining packs totaling 150 to 200 animals.

Colorado initially struggled to find wolves to reintroduce into the state. After Wyoming, Idaho, and Montana declined to offer wolves, Oregon agreed to transfer ten wolves, with plans to trap and transfer the wolves from northeastern Oregon to Colorado.

The reintroduction comes with mixed accolades and concerns. While wolves outside of the Northern Rockies are protected under the Endangered Species Act, they will be labeled as an experimental population in Colorado. Officials say that this will allow for wolves to be managed in the event of livestock depredation.

Preparing for wolves among livestock

Wolves have already been crossing over into Colorado from Wyoming since 2019, establishing a small pack named the North Park Pack. Ranchers in the area report that dealing with the apex predators has necessitated changes in management style, something that other livestock producers will face in the coming months and years.

Colorado Parks and Wildlife have confirmed that wolves from Wyoming have killed five dogs, 13 cattle, and, most recently, three lambs. At least four members of the eight-member North Park Pack were legally shot and killed along the Wyoming border.

According to state laws, the wolves must be released west of the Continental Divide, at least 60 miles from a sovereign tribe’s land or a neighboring state, and not on federal land managed by the Forest Service, Bureau of Land Management, or National Park Service.

Releases are set to occur near Grant, Eagle, and Jackson County, where over 200 ranches operate with 30,000 head of cattle.

“Most people in the counties with the strongest support for Proposition 114 — Boulder with 68 percent and Denver with 66 percent — probably won’t encounter a wolf on a regular basis,” wrote the Colorado Sun.

As an apex predator, Colorado Parks and Wildlife officials say that the wolves in Oregon feed primarily on elk, which have a healthy population in the state of Colorado. One adult wolf can eat and kill as many as 20 elk each year. However, wolves’ ability to travel 30 miles per day means that the territories they land in may be any number of ecosystems … or ranchers.

The state’s wildlife agency says that they’ll loan deterrents such as LED lights, cracker shells, propane canons, and electrified fences to ranchers near the release sites.

When prevention fails, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife rule allows ranchers to kill wolves caught attacking livestock or people. Compensation for livestock killed by wolves allocates a fair market price of up to $15,000 per animal, allowing the same amount for veterinary costs associated with wolf-related injuries on livestock.

So far, the state has $175,000 set aside to pay for killed and injured livestock in the first year and $350,000 for each year after.

Wolf reintroduction is a polarized issue, and CSU studies look to explain why

Other concerns have been voiced by Colorado residents who are worried about wolf-human conflict. In the 1940s, when wolves were first eradicated, the state’s population was just over 1.1 million. Now, the state boasts nearly 6 million residents.

A study was conducted by Rebecca Niemiec, assistant professor in the Human Dimensions of Natural Resources department at Colorado State University’s Warner College of Natural Resources.

Niemic’s study, published in the Conservation Science and Practice, looks at why the 2020 vote to approve reintroduction was so close despite 25 years of historic support for wolf reintroductions.

“When survey respondents were asked why they voted for or against the reintroduction of wolves, a common response was the ability to restore ecological balance, improve the environment, and the belief that protecting wolves was the right thing to do,” summarizes CSU.

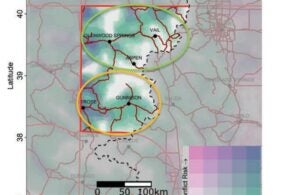

A second study published in Ecological Applications by Mark Ditmeer, a postdoctoral researcher at the Center for Human-Carnivore Coexistence, evaluated social and ecological voting patterns of the 3 million voters who participated in voting for or against Proposition 114.

“The study found that voter support for Proposition 114 had a strong positive relationship with voter support for President Joe Biden,” reads a summary. “Additionally, the study found that younger and more urban voters had greater support for the initiative, whereas areas with more elk hunters had less support.”

Areas closer to where wolves had been detected and where the reintroduction process was slated to happen tended to have less support for reintroduction when compared to the rest of the state.