It smells like corn spirit. Or does it?

Across the Corn Belt, you might notice yourself sweating due to the increased humidity during June and July. Some blame the corn. “It creates its own atmosphere,” some say, while complaining about corn sweat.

“Using the term ‘corn sweat’ is kind of funny,” said Trenton Ford, Illinois state climatologist and hydroclimatologist. “It’s not perfect as with most metaphors. Humans and a few other animals will perspire when we get hot, and sweat is evaporated off our skin. What corn does is a bit of a different process.”

Transpiration, or evapotranspiration, is the term used to explain this phenomenon. The process is common across the plant world. Think of it as breathing, but instead of carbon the plants expel oxygen.

“The movement of water through this system is like a plant’s circulatory system,” said Talon Becker, University of Illinois Extension commercial agriculture educator. “It’s how they move, nutrients and other mobile health things throughout the plant as well.”

The process happens in three main steps:

- Plants absorb water from the soil through their roots.

- Water is transported through plant tissues, where it plays a role in metabolic and physiological processes.

- Leaves release water vapor into the air through their stomata.

But why the term corn sweat? Becker has some theories.

“We anthropomorphize things to better understand them,” he said. “Giving that sweating something we do and we understand it, it’s a similar idea.”

He said the plants release vapor through their stomata like humans excrete liquid water through our pores. Another theory: We simply associated the humidity with sweating, thus associating the corn with sweat.

Is corn to blame for the humidity? Not entirely.

“[Corn] can augment the humidity, but it’s not the main contributor,” Ford said.

During high-humidity months, corn sweat can garner national media attention. But those stories can too often point a finger at farmers rather than take a more nuanced understanding of corn’s bit part with humidity.

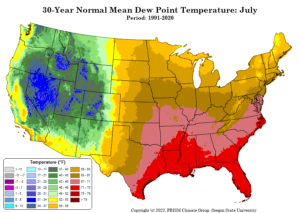

Midwest humidity can largely be attributed to moisture from the Gulf of Mexico, Ford said. During this time, warm, moist air comes from the south, creating the humid atmosphere across the Midwest. Plus, waterways and other plants like soybeans also add moisture to the air.

“There’s a lot of forces at play in the middle of the summer,” said Meaghan Anderson, Iowa State University Extension and Outreach educator and field agronomist. “If you live in Iowa, you can’t avoid seeing all the corn in July. But it’s just one of many forces that time of year affecting our temperatures and humidity levels.”

In fact, Becker said some research finds soybeans are a larger contributor than corn.

“The misconception might be that if there were no corn, then it wouldn’t happen,” Becker said. “That’s just not true. All grasses and all plants are going to transpire.”

The transpiration process is a sign of healthy plants and the health of its surroundings. When plants become stressed, like during a drought, they close their stomata to conserve water, Becker said. This defense mechanism can limit the plant’s growth.

“When the corns plants are ‘sweating’ as much as they can, that plant is growing and producing as best as possible,” Becker said. “They also sequester as much carbon as a possible.”

The closed stomata doesn’t only mean less water in the plant, it means less moisture in the atmosphere, Ford said.

“A lot of transpiration and humidity is a good thing for crops because it means there’s moisture available in the soil, the crops are successfully photosynthesizing, and they’re doing what they need to do to produce yield at the end of the season,” Anderson said.

The goal for Ford and others is to focus on research to better quantify data on transpiration and humidity.

“There’s a common assumption among folks who aren’t in the weather community that we can measure everything, and are measuring everything,” Ford said. “That’s just not the case.”

One solution to measuring transpiration is using satellite remote sensing, Ford said. An ongoing gain in the science is better measurement of all aspects, he added.

The driving factor for the research is not public health, like in other climate-related fields, but rather with drought.

“If we coupled lack of precipitation through to high demand from the air, high temperatures, low humidity, and the effects of transpiration that could lead us to better understanding drought,” Ford said.

Research could help create better drought monitoring and prediction processes, Ford said.

How do farmer’s feel about the humidity? It is probably a mixed bag.

“I don’t know, maybe that’s why some of them travel other places during the winter,” Anderson said.

No matter what you call it, corn sweat or corn breath or transpiration, remember that humidity is due, in part, to healthy plants.

Braeden Coon holds dual degrees from Oklahoma State University in agricultural communications and animal science and has a master’s in journalism from Northwestern University.