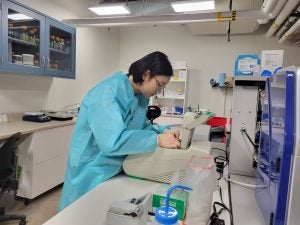

Growing up, I did not get a lot of exposure to scientific laboratories or research. In my first chemistry wet lab as an undergrad at UC Davis, I remember struggling to use a pipette bulb and almost crying because everyone seemed to know what they were doing while I struggled.

Looking outside and seeing an unfamiliar campus and knowing that I was so far away from home made me wish I could leave and return to my family — to what was familiar.

This feeling of being out of place has followed me throughout my career. As a minority female in STEM, it can be discouraging to know that I don’t see familiar faces in my work or that others won’t be able to connect to my experiences as a low-income, first-generation scientist.

At UC Davis, I became interested in the intersection between research and agriculture — the school is a hub for agricultural sciences and plant biology studies, and I was keen to enter the field and contribute. While my education and internships had prepared me for feeling like a minority in STEM, I was not prepared to again feel like a minority in the agricultural sector.

My first job after graduating was as a research field aide with Morning Star Trucking Company, a company that specialized in trucking tomatoes from the field to the cannery. This position gave me valuable insight into what the agricultural research industry looked like, from maintaining large-scale field trials to meeting growers.

As an Asian female, I definitely did not fit the typical image of what many growers were expecting to see. It contrasted with the stereotypical image of a farmer, who is White, male, and a generational grower. Simply by being present in this industry, I drew a lot of skepticism and comments that I was not prepared to handle. I was often asked why I was working in the field, because I did not look like someone who would be interested in agriculture. My leaner body frame coupled with my identity also drew comments on whether I was tough enough to handle the workload that farms often demanded.

At many times during my work shifts, I felt isolated and lonely, that I didn’t belong in this industry because I didn’t fit in. This alienation felt like a driving force that was subtly pushing me out of this industry, and I struggled to see what value I could contribute to the sector. I decided that being in a research laboratory focusing on plant biology was more befitting, and I felt that it was from this vantage point that I could contribute to society.

One aspect of isolation that I was unprepared for, however, was the rejection of plant biology researchers by farmers and growers. A lot of traditional growers were wary of researchers, who oftentimes did not have any hands-on field experience growing crops for production purposes. Growers were distrustful of researchers, and researchers in turn often looked down on growers, feeling that they were intellectually superior and were more of an expert in agriculture than growers were.

Learning about this nuanced divide between agricultural researchers and agricultural growers was something I struggled with, and it felt like I had to choose between these two camps.

It wasn’t until I attended Penn State for a Master’s in Horticulture that I learned how researchers and growers can work collaboratively to improve crop yields and health. Here, I saw that everyone was united to improve agricultural conditions – that people drew upon their strengths to achieve their goals and relied upon others when they needed help.

My experiences at Penn State helped me grow in my career, and showed me that I can carve out unique contributions to the agricultural sector in whatever way I see fit — as a farm hand, researcher, or even scientific communicator. When you have passion and resilience, the possibilities of where your interests take you are boundless.

For people who are underrepresented or minority groups on the fence about whether they belong in science or agricultural sectors, you definitely belong. The contributions and innovations that you bring can make lasting impacts to the field. While it can be tough to feel isolated and lonely, know that your passion can act as a buffer while also helping you connect to others who are also passionate about the same things you are.

» Related: Belonging in ag: The journey to find my fit in this industry

As the future of STEM and agriculture changes, so too will the faces of those who represent it.

Today, I believe that the future of agriculture can only be built if we work collaboratively. Given the dire situations of climate change, increasing populations, crop susceptibility to disease and stresses, and emerging ethical opinions on how to grow food, the entire industry of agriculture must undergo change and innovation in order to continue serving society.

To do this, everyone in the agricultural sector, regardless of their sub-specialty, must work together to help solve these problems.

Liza Thuy Nguyen serves as the 2023 American Farmland Trust Agriculture Communications Intern at AGDAILY, with a focus on helping to amplify diversity and minority voices in agriculture. Liza is originally from Anaheim, California, and attended the University of California, Davis, as a first-generation college student. She received a bachelor’s degree in genetics and genomics and went on to earn a master’s in horticulture from Penn State.