Synthetic nitrogen fertilizers have become so costly to farmers, the energy sector, and the environment that everyone seems open to alternatives. But in today’s high production systems, driving profitable crop yield demands specific plant nitrogen levels.

New research from North Carolina State University’s Department of Crop and Soil Sciences will investigate whether enhanced efficiency fertilizers (EEFs) could benefit both farm profitability and the environment.

Nitrogen everywhere but here

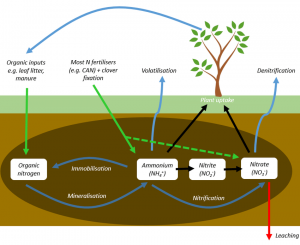

Nitrogen is an essential nutrient for plant growth. In a sustainable cycle, nature employs multitudes of soil bacteria to convert the abundant atmospheric nitrogen into plant-usable forms.

But when the system is overloaded from high nitrogen rates or poor application conditions, environmentally damaging ammonia and nitrous oxide gasses can be released from the soil in high amounts. A farmer’s pricey nitrogen investment can literally disappear into thin air.

Urease and nitrification inhibitors improve nutrient-use efficiency

NC State assistant professor Alex Woodley is leading a new study funded by a U.S. Department of Agriculture Natural Resources Conservation Service Conservation Innovation Grant to evaluate the effect of dual urease and nitrification inhibitor-spiked fertilizer to mitigate nitrous oxide and ammonia emissions — and to potentially reduce nitrogen inputs.

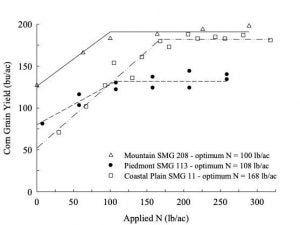

“Traditional nitrogen application rate recommendations are crop-response driven. Typically, at 150 to 250 pounds of nitrogen per acre, we see the most economic benefit in corn. But we don’t account for nutrient losses due to soil cycling, which is both financially and environmentally troubling,” Woodley said. “Using EEFs can help reduce these losses.”

Woodley’s group plans to test nitrification inhibitors mixed with the most commonly used forms of agricultural nitrogen (UAN and urea) to create an EEF. Inhibitors work by slowing or halting the natural nitrogen cycling process, ideally keeping the nitrogen in the ammonium form and giving plants first dibs (and more time) to uptake the valuable nutrient.

Historically, nitrogen application rates have losses factored in, but EEFs could significantly increase a crop’s nutrient use efficiency with nitrogen.

“The nitrogen cycle is a leaky bucket,” Woodley said. “Soil nitrogen is hard to retain. Up to 50 percent of applied nitrogen can be lost in soil cycling through a combination of volatilization, leaching or nitrous oxide emissions. So, as little as half of what a farmer paid for (and crops need) may actually be going to its intended use.”

Moving nitrogen from risk to reward

Woodley’s three-year study will compare EEFs at various nitrogen application rates compared to untreated regular UAN fertilizer across six corn plots per year on private farms in eastern North Carolina. (The state is the largest corn producer in the Southeastern U.S.)

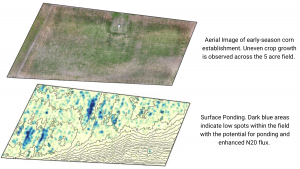

The group will use soil emission-monitoring chambers to measure gas release and multispectral drone imagery to assess field variables that accelerate nitrogen losses.

Previous research on these types of EEFs has shown a mixed impact on crop yield. Warm, rainy seasons, sudden rain events or windy, hot conditions after nitrogen application cause nitrogen to leave the system and crop yields to suffer. But in ideal weather and application scenarios, farmers often don’t see any yield increase from EEFs.

On the surface, EEFs appear to merely offer farmers a nitrogen-availability insurance policy — at an added cost.

“We talk about hot spots and hot moments for gaseous soil emissions. The season’s weather, application conditions and micro-climates in a field can dramatically impact off-gassing — from virtually none in cool, still conditions up to 50 percent in hot, windy scenarios,” Woodley said. “EEFs used to be viewed as an expensive risk-mitigation tool, particularly for urea-based fertilizers.”

With nitrogen input costs skyrocketing (up 100 percent in some areas) and availability unstable, the insurance potential alone might appeal to growers. But if nitrification inhibitors can fend off bacterial nitrogen processing and preserve its availability for plants, couldn’t a farmer get away with applying less fertilizer overall?

Woodley says, “Bingo.”

“We think we could potentially reduce nitrogen rates 15 to 20 percent for a substantial environmental benefit with no negative impact on yield,” Woodley said. “And because inhibitors are only soil active for two to three weeks before breaking down, they are relatively low risk. Unlike excess nutrients, at the end of the season, you never know they were there.”

Because Woodley’s research will capture field variability and emissions, future EEF recommendations could even be tailored for variable rate application or spot use in problem zones like low areas and wet spots.

Importance in N.C.’s coastal plain

Nitrogen fertilizers are a well-known contributor to troubling nitrous oxide emissions. However, ammonia emissions are less often accounted for, but are also risky, especially to aquatic ecosystems.

Because North Carolina’s prime agricultural land lies in the coastal plain, the state’s rivers and coastal estuaries are especially vulnerable. Nitrogen leaching and ammonia production over-stimulate microorganisms, producing harmful algae blooms and reducing water-dissolved oxygen levels for aquatic life.

“Nitrous oxide is a hot topic right now because of the government’s interest in climate mitigation. But because of ammonia’s water and air quality risks, we think it will become increasingly important in EPA monitoring and potentially conservation incentives,” Woodley said. “It’s already become a management priority in Europe.”

Most research on EEFs has been conducted in the organically rich soils of the Midwest. Eastern North Carolina’s coarse-textured soils and hot, humid conditions pose different challenges and risk-reward opportunities.

Controlling the pace of nitrogen cycling, and potentially the amount of nitrogen applied, would be an environmental win on both accounts.

“We’ve seen amazing results from inhibitors in other areas of North America in ammonia volatilization reduction,” Woodley said. “But we need to closely examine how inhibitors will function in the hot, humid conditions and coarse soils of eastern NC. There could be even more benefits here, as these are the conditions for high ammonia losses.”

Farm revenue beyond yield

If nutrient use efficiency and environmental benefit weren’t enough incentives to inspire EEF adoption, the emerging carbon market might offer even more.

NC’s sandy coastal soils are notoriously difficult for carbon sequestration, leaving these growers at a carbon-revenue disadvantage compared to their Midwestern counterparts.

However, pilot projects are popping up throughout the U.S. that incentivize farmers to adopt EEFs in their system. For example, Bayer, in collaboration with CHS Farmers Alliance, is paying farmers $3 per acre to use EEFS.

“Irrigation and nitrogen fertilizers are often the two most energy-intensive processes on a farm,” Woodley said. “Improving nitrogen use efficiency and reducing nitrogen inputs with EEFs could significantly lower the global energy footprint of agriculture and potentially open a new revenue stream for NC farmers.”

Woodley’s EEF study is an added layer on Climate Adaptation through Agriculture and Soil Management’s (CASM) private donor-funded greenhouse gas research and is a part of the N.C. Plant Sciences Initiative.